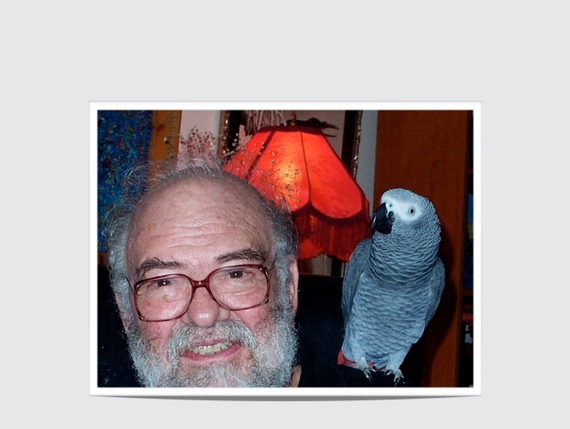

The author and his African grey in younger years

More than 40 years ago, my then-wife Nigey Lennon and I were on our way home to Echo Park when, suddenly, she said to stop. I thought it was because she'd spotted a garage sale. Instead it was a woman who had set up a bunch of cages with cockatiels for sale. Some were in the cages, and some stood on top of the edge of the cages.

"Oh, hell," I said. "I don't want birds. They're messy and they're, well, bird-brained. Stupid."

Nigey prevailed, of course, and as we approached the birds, I was amazed to discover that, as we were looking them over, they were giving us the once-over. That unnerved me. And it began a process whereby I came to realize we share this Earth with a lot of creatures who are every bit as sentient as we are.

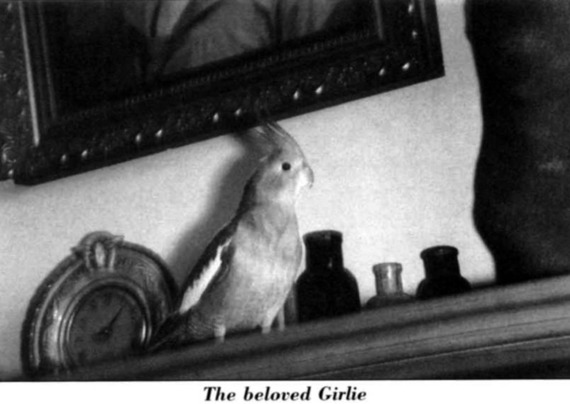

Over the next few years, other birds impinged on my life and took me into their soap-opera lives. The bird we bought that day was named Mo. Gurly came next because we walked into a bird store on Melrose Avenue near my old alma mater, Fairfax High School, in Los Angeles. As we walked around the cage, one rather drab gray bird was intently following us with her eyes and body. She peeped and squawked, obviously saying, "I'm here. Look at me. I want to be with you guys."

She just had to come home with us. She was an incredible creature, and when she died, I mourned her like I would a human being. We named her Gurly.

Gurly was a pothead. A friend sometimes used to leave a red canister with pot on the table, and the moment she spotted it, Gurly would make her way to the canister and work until she found a way to take the lid off. She didn't smoke, of course, but she loved to eat the seeds, twigs and leaves. After partaking, she would fly around like she was stoned, or at least inebriated. When she got pregnant and Mo would come around to check her out in her eggs, she'd scare him away. She would begin by flapping her wings and squawking, but then she discovered that if she rang the bells inside her cage, it would drive Mo away just as bagpipes were first used on the battlefield to vanquish enemies.

One day Mo was left alone with Gurly in the bathroom while the sink was getting filled with hot water. Mo, not being as smart as Gurly, jumped into the water and started flapping and drowning. Gurly began shrieking and hollering until Nigey came in and saved Mo.

I know you could say that Gurly's brilliance in getting at the pot was only that intelligence all beings have when it comes to finding food. It's surprising how smart creatures, from insects to felines, are when their dinner is at stake.

It was inevitable that we would move up the ladder of birds. A friend decided I needed an African grey, particularly one she had found hiding in mourning in a pet store. Nick's previous human partner had been a motorcyclist who spoke in a gruff, Satan's Slaves voice. When he died in a collision, Nick went into deep mourning, staying completely silent. The motorcyclist's family wanted Nick gone. He was left alone in a pet store.

When we first brought Nick home, he said nothing for a couple of weeks. Then one day Nigey walked into the bedroom with a doughnut. Nick said, "Have you got some more cookie?" quite insistently. Nigey quickly realized that the Professor, as we began calling him, could be mollified with a piece of doughnut. We also both learned that when the Professor was asking for a "cookie," you could tell by his tone of voice if he could be satisfied with a cracker, a piece of bread, or a rub of the head. All these things meant "cookie" to Nick. In fact, his "I want a cookie" or "Have you got some more cookie?" or just "Cookie, cookie" could become quite annoying. One day he was being insistent with me, and I was ignoring him. He kept asking for a "cookie" and becoming more annoying with each new utterance. Still, I kept ignoring him; I was trying to get something read. Then I heard him say, "Come here. Bring your Nick a cookie." I stopped reading. I realized that Nick had just completed a genuine sentence. I later learned that I shouldn't have been surprised; there was one famous African grey named Alex who was the subject of experiments at Tulane University. Alex not only had an ability to distinguish letters of the alphabet and the names of colors; he could also read their names from cards. Alex also made up pretty good poetry. So when Nick gave me a direct command, I acquiesced. "Yes, Nick. For that you get a cookie." And I got up and went to the kitchen to get my Nick a cookie. He had me well trained.

After a while, Nick graduated to standing on top of his cage. One day my dog Rosie, half German shepherd and collie and half coyote, who had been born in Griffith Park, came into the room. She saw Nick out of his cage. Rosie lunged at Nickie. Nick spoke up, sounding angry. "Bye, bye," he repeated, and hissed and carried on, and then bit the dog on the tail. After that, Rosie never lunged or said a word against these strange feathery creatures who spoke like people. She even allowed the cockatiels to ride around the house on her, without complaint. After that, Nick's dominance over Rosie was all psychological bluff and bluster, for Rosie would have been quite capable of devouring Nick in a second had she known her own strength.

The larger question of "animal intelligence" has always intrigued me. When I was a youngster in Long Beach, a port town to Los Angeles where the Navy had a lot of facilities, my parents often had Dr. Fitzgibbon over. It was the early '50s, and he was obsessed by his experiments with dolphins. He was working on top-secret research for the Navy and wasn't supposed to talk about it, but he'd harangue my parents for hours talking about dolphins -- about how smart they were, how they might be smarter than Homo sapiens.

Homo sapiens have the advantage of the opposable thumb, meaning we can grasp tools and make printing presses and schools and museums and libraries to continue our culture from generation to generation. Dolphins and other beasts have the disadvantage of having to pass on their knowledge only orally.

But, Fitzgibbon noted, the dolphin's brain had a much larger capacity than ours and processed information much more quickly than ours, and dolphins had a more complicated syntax.

Surrounded as I was by my little dinosaurs in the bedroom, I began to contemplate this question of animal intelligence. While the notion that dinosaurs were the ancestors of today's avians had been suspected since the time of Darwin, it wasn't until the '80s, with the publication of Yale paleontologist Robert Bakker's The Dinosaur Heresies, that the notion really stuck.

Nigey and I met Bakker, and he told us about the African grey he used to work with at the Brooklyn Zoo. He said he thought African grey birds the most intelligent animal on the planet, save ourselves. He thought African greys were more intelligent than chimpanzees, orangutans, dolphins -- the whole lot of them.

Soon, Hammy, a blue-fronted Amazon, joined the flock in our converted porch bedroom. Upon occasion, when Nigey began singing jazzy tunes, Hammy and Nicky would join in. I'm not sure it was great music; it sounded like music school meets lunatic asylum. Hammy was a great improviser, in bits and pieces. Her problem was that she hadn't a long-enough memory to be a consistently good musician, but there was music in her soul. Nick, on the other hand, loved to sing the music to the movie The Bridge on the River Kwai and obviously knew the melody but had a tin ear when she tried to whistle it.

I also came to realize that it wasn't just parrots who were smart. One wintry day in 1989 in the Sierra, Nigey and I were driving out of the mountains, chased by an evil-looking storm. We were driving down the eastern side of the Sierra, not yet having crossed over the Nevada state boundary on our way into California, when we saw a truck driver standing in front of his truck, parked at the side of the road. The driver was looking down at a magpie that he had run over, and its mate, just inches away, was grieving in loud, unmistakable tones that I imagined any human being or animal would understand as grief. The driver also looked distraught. Just before we came on this scene, we had been commenting on the flocks of magpies, who, despite their grumpy name, are beautiful-looking, sleek, black birds with vivid white stripes on their wings -- close relatives of crows and ravens.

I later read about magpies. It turns out they are like the Irish. They have a wake when one of flock dies. So the lady magpie's rant against the man who had killed her husband -- well, it was easy to identify with.

Konrad Lorenz, the author of King Solomon's Ring and one of the great early pioneers in studying birds, lived in a village with a cockatoo that was a constant companion. But the bird lived outside Lorenz's home, and when Lorenz used to finish his work and then visit various pubs in his village, the cockatoo would go to the different taverns asking if the doc had come in yet.

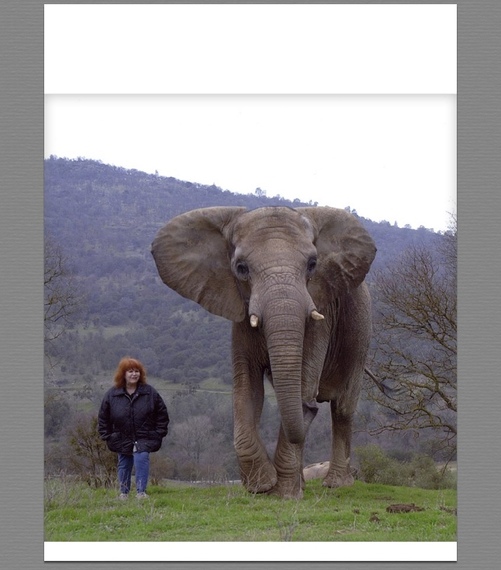

I discussed this matter of animal intelligence with a friend of mine, Pat Derby, a former movie animal trainer who wrote The Lady and Her Tiger in the '70s and then retired to the Sierra to run an elephant sanctuary. She famously provided a home for a couple of the elephants that had been treated badly at the Los Angeles Zoo.

Pat Derby and friend

Derby pointed out the obvious, which does not mean it isn't profound. Elephants are the largest creatures on the land, just as whales are the largest creatures in the sea, she said. Derby notes that both the animals have been tormented by Homo sapiens.

In the case of elephants, "They have to learn to tolerate a great deal as they adapt and adjust to humans," she said. "In my opinion, that shows they are so much more intelligent than we thought. They are capable of making the adjustments to things that are totally foreign to their real nature. They manage to survive in situations that sorely test their minds, and from which they sometimes die. Simply put, animals deal with human beings who are control freaks."

Animals "are so ahead of us. We go to church. We study, we meditate, always trying to seek the truth about ourselves, to discover ourselves, to find inner peace. Elephants just have that inner peace. You just look at them, and wonder, where does it come from?" she said.

Lionel Rolfe is the author of a number of books available in Amazon's Kindle Store and in paperback. On Dec. 11 at 7:30 p.m., his book Literary L.A. is being feted at a "Lionel Rolfe Author Tribute" at the Warszawa Loft, 1414 Lincoln Boulevard, Santa Monica, in an event put on by the Public Works Improvisational Theater.