"Why can't we go to Legoland?"

That's really how it all started. Our 9-year-old son had come home from school one day, excited that his school was having a blood drive. If we donated blood, we'd be rewarded with a few tickets to Legoland. As two dads, we suddenly found ourselves thrust into an unexpected conversation with our very inquisitive (and Lego-loving) son about sexual orientation, HIV, and the Food and Drug Administration ban that prevents gay and bisexual men from donating blood. To his disappointment, we couldn't participate in his school's activity, despite the school's pride in its firm commitment to nondiscrimination and inclusivity. If this was happening to us, surely it was happening to other gay and bisexual men at their kids' schools, places of worship and other community gatherings. Even more importantly, it meant the country was struggling with a smaller-than-necessary supply of safe blood in an environment where blood was constantly in short supply.

I decided to approach the school's Board of Trustees, but I did so reluctantly. If they cancelled the blood drive, the only people who would likely suffer would be the people who needed blood. Nevertheless, my husband and I were at no greater risk of transmitting HIV than our straight neighbors. There had to be another way.

The FDA ban provides that if you're a man who has had sex with another man (or "MSM," as they affectionately refer to you) even once since 1977, you're permanently deferred (banned for life) from donating blood. In 1983, when less was known about how the HIV virus was transmitted and how to test for it, this policy helped maintain the integrity of the blood supply to some degree and presumably reduced the cost of blood collection. But today we recognize that HIV transmission is not limited to gay and bisexual men. We recognize that modern testing techniques like Nucleic Acid Amplification testing can reveal the presence of HIV in the bloodstream in an average of seven to 10 days from the date of transmission. We know that every unit of blood is tested for HIV, regardless of how a potential donor answers questions during the pre-screening process.

But wait. Don't gay and bisexual men still contract HIV at a higher rate than the overall population? Yes, and this has long been the rationale for the FDA ban. While it's easy to potentially rely on this statistic, it's not the fact that men are gay or bisexual that puts them at higher risk. That may be an attribute, but it's not the cause. It's one's behavior that puts one at risk, and that relationship between behavior and risk applies regardless of one's sexual orientation. Straight, gay or bisexual, if you engage in risky sexual behavior with a partner of unknown HIV status or HIV-positive status, you're at risk. If you don't, sexual orientation is irrelevant. All else being equal, an HIV-negative man in a long-term, monogamous relationship with another HIV-negative man is not at risk, yet he is permanently banned. Conversely, a straight man routinely having condom-less sex with multiple women of unknown HIV status is not permanently banned. Intuitively, it's easy to see that by asking the right questions about sexual behavior instead of sexual orientation, we have the chance not only to expand the eligibility of certain donors but to possibly make the blood supply even safer than it is today.

So why is the FDA slow to respond? It wants data -- its own data, not data from other countries. Moreover, there is already an established acceptable level of risk in the nation's blood supply. Changing blood donation criteria, especially if the FDA considers tightening restrictions on the straight community to make the blood supply safer, can dramatically affect the blood supply. The FDA must understand these implications. (See this Williams Institute study.) Finally, there's the "ick" factor. Many who believe homosexuality is wrong, citing moral or religious convictions, remain staunchly opposed to accepting blood from gay men. Scientific or not, it's just icky to them. Standing up against groups like these will require strength and resilience from the FDA.

Within the LGBT community itself, many live at the intersection of being both LGBT and HIV-positive. They simply don't draw a distinction between these dual identities, and, frankly, they shouldn't have to. Politically, given the rate of HIV infection among men who have sex with men, and among transgender women, there's a critical need to for us all to work together as both HIV/AIDS and LGBT advocates. Addressing the ban is part of that work, although it's certainly not the only work to be done.

Does the FDA's current MSM blood donation ban rise to the level of discrimination? Perhaps not, in the sense that no fundamental right to donate blood has been declared "guaranteed" by the U.S. Constitution. Perhaps not, in the sense that the FDA has the right to create appropriate policy when it's in the best interest of public safety. But consider the effect of this overreaching ban on our son's school. During its debate on the issue, the school entertained the possibility of an implicit exception to its own nondiscrimination policy because such discrimination was "federally sanctioned." It actually considered poking a powerful hole in its own nondiscrimination policy due to FDA policy! This becomes particularly disturbing when considering that a blood drive, while vital and altruistic, is nevertheless a nonessential activity to a school's primary mission: education. If this can happen in a school, aren't other businesses and organizations holding traditional blood drives poking similar holes into their own nondiscrimination policies? In this sense, an overreaching FDA policy could certainly be viewed as discriminatory.

Something good did arise from our son's blood drive experience at his school. We developed an inclusive blood drive, where everyone could participate. Ineligible donors found others who could donate on their behalf, and we honored those participants who were unable to donate for themselves. We educated people about the ban. Hopefully, we began to inspire change. And yes, our son eventually made it to Legoland.

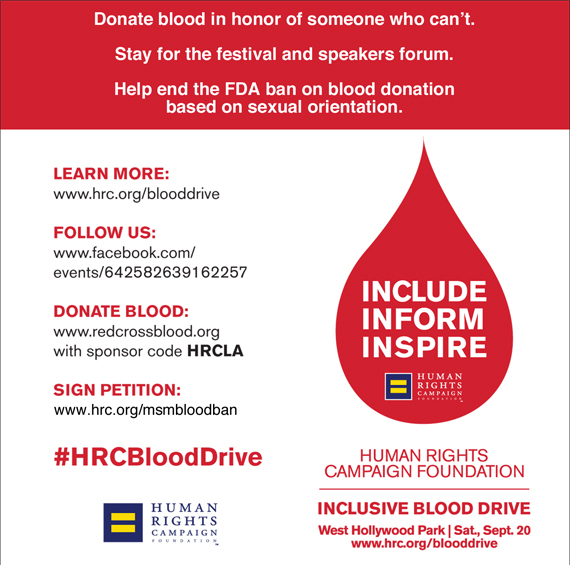

On Sept. 20, the HRC Foundation will embark upon its first Inclusive Blood Drive in the West Hollywood/Greater Los Angeles area, along with other organizations like the City of West Hollywood, the Los Angeles LGBT Center, the Trevor Project, the Gay Men's Chorus of Los Angeles, Vox Femina, Love Don't Hate and the Pop Luck Club. We also acknowledge the significant efforts of two other team members: Banned4Life and Love Don't Hate (producer of the National Gay Blood Drive). These two organizations have committed themselves to changing FDA policy. Together we ask the FDA, and the entire country, to take yet another step in the evolution toward full LGBT equality. We envision a day, very soon, where a man's sexual orientation no longer plays a role in his ability to donate blood.

More info: hrc.org/blooddriveDonate blood: redcrossblood.org using sponsor code HRCLAFollow Us: Facebook Event Page and #HRCBloodDrive

Used with permission from the Human Rights Campaign Foundation