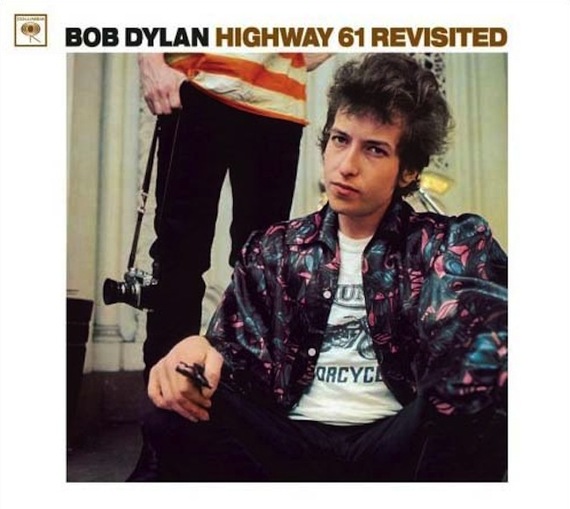

Bob Dylan, Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

© Sony Music Entertainment, album cover photography by Daniel Kramer

"Desolation Row" is over eleven minutes of anything, everything. For nearly fifty years, Bob Dylan's fans, critics, and writers have been trying to say what it's about. To me, it's a song I love to listen to, and one of the last great works of Modernism.

Early Modern poets loved allusion, and music. More about allusion as we go. T.S. Eliot, like Dylan a fan of the music hall and vaudeville, worked that Shakespe-he-rian rag and kicky little bits like Mrs. Porter and her daughter into The Waste Land; and F. Scott Fitzgerald often used bits of jazz and popular songs in his fiction. W.B. Yeats chanted out his verses as he wrote them, and experimented with archaic arrangements and instruments. Yeats wrote the words first, and then looked to music -- the reverse of Dylan's creative process as we see it documented at the piano in D.A. Pennebaker's Dont Look Back (1967).

If you scan "Desolation Row," a debatable thing to do to a song not designed as a poem, it runs in a long-short line pattern, with perfect phrases of iambic trimeter (the circus is in town, on Desolation Row) regularizing the rhythm. Rhymed lines are separated by those that aren't. The singer is your carnival barker, and the thin ribbon of Charlie McCoy's Mexican guitar laces everything together.

The Row isn't confined to, as Dylan said long ago, "someplace in Mexico," but most surely it's a dusty bordertown. Who are the scary "they," and why do they sell postcards of a hanging coincident with a circus, put the blind commissioner in a trance, nail the curtains, spoonfeed Casanova (originally "with the boiled guts of birds"), and round up everyone that knows more than they do? Desolation Row is a police state, but, paradoxically, lawless too. It's rather like John Steinbeck's Cannery Row, that pre-hippie California community of Chinese shopkeepers, bums, prostitutes, a mysterious doctor, ice-pick suicides, hound dogs, and couples living in abandoned machinery. However, Cannery Row is a safer, more pleasant place to be, redeemed by the sea.

Characters in "Desolation Row" are familiar, but none in recognizable guise. Here's where Dylan's reveling in allusion kicks in. Romeo is present, but instead of courting Juliet he is moaning a song released by Patti Page in 1952. Lon Chaney, a favorite actor of Dylan's, presents two of his thousand faces: the Hunchback of Notre Dame, and the Phantom of the Opera. Einstein materializes not with his Nobel (awarded in 1922, by the way, the year of Modernism's greatest hits from The Waste Land to James Joyce's Ulysses, Fitzgerald's Tales of the Jazz Age, and Virginia Woolf's Jacob's Room), but his violin, which he enjoyed playing in real life. Eliot and Ezra Pound appear, fighting in the captain's tower of the doomed Titanic as people shout "which side are you on," less a protest song than reminder that cabins on the port side out, starboard home mean you're posh. In an image reminiscent of the close of Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock -- completed when Eliot, too, was still in his twenties -- lovely mermaids flow in with the sea. Like Eliot, Dylan ends with human voices. The last stanza is a direct address to "you." Have we just met people here we know, with rearranged faces? If you want to contact the singer, do you really want to go to Desolation Row for that postmark? Worst of all, are you already there, standing on that balcony with Lady, be she woman or dog, and the singer?

Yes, we are all on Desolation Row at the end. You have to be there to write the singer, but there's no evidence he's left -- or that he wants to. Arrested departure is rife in Modern writing: its hurry-up-and-wait leaves you stuck on a beach wondering about rolling your pants up, if you're Prufrock; and still in Dublin, not yet in Paris, if you're Stephen Dedalus at the end of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Speech acts are the great cheap non-exit from Modernist literature: those who can't do, say, and then pretend that to say it is as good as to do it. Nope. You're just all talk, no action.

Despite the mermaids, "Desolation Row" is far more a Waste Land than a Love Song, packed with allusion like all those great Modern texts of 1922. Modern writers, especially Joyce, wove lines into their work that they thought, or assumed, everyone should know. If you look at Eliot's original draft of The Waste Land, with Pound's corrections, you see the line "these fragments I have spelt into my ruins" changed into "these fragments I have shored against my ruins."

The word that best describes Modernism to me is mosaic. A mosaic is made of fragments, bright bits that catch the light on their own but come together into a masterpiece. Modern writing, art, and music contain sometimes dramatic, sometimes playful, and always referential reworkings of celebrated cultural moments, details, and artifacts for one's new artistic purposes. Eliot referred famously to this as a conjunction of tradition and the individual talent. I think of it as renewing: Giacometti, his sculptures inspired by African folk carvings; Copland and Schoenberg using earlier compositions in their own; Picasso's rich strange versions of Old Masters and El Greco; Yeats working repeatedly with Cuchulain, Ovid, and Blake. Dylan's acknowledged influences and namecheckings in "Desolation Row" help to make of him not only (to swipe the title, and mantle, from Yeats) the last Romantic -- Lord Byron Dylan, as once upon a time young Dylan signed himself -- but also the last Modern poet. However, when Dylan heeds Pound's celebrated injunction to "make it new," these days, he is renewing not others but himself, revising musical arrangements of old songs, and re-envisioning his own images and symbols: circuses, cars, chosen times in American history, southwestern towns, wandering troubadors, broken desolate streets, hotel rooms, particular blues riffs, motif moments. Yeats called his most precious symbols and themes "circus animals" in one of his finest late poems -- a festival way to think of what recurs in "Desolation Row," and in works of Bob Dylan's from then to today.

© Anne Margaret Daniel

read my article on Dylan's whole album Highway 61 Revisited for Montague Street (2010) here