Beijing may be several thousand miles away from London but the British vote to leave the European Union will also affect China. Politically, Beijing stands to gain a great deal from Brexit. The uncertainty over the future of London's financial industry will enable Beijing to use the internationalisation of its currency, the Renminbi (RMB), as a strategic tool to strengthen its bargaining position in European capital markets. At the same time, the potential loss of access to European markets means China looks more attractive to the UK than ever. This will give China bargaining power, making it easier to secure favourable bilateral agreements. The weakening of the Sterling will also benefit Chinese investors looking for opportunities to buy UK corporate assets at a discount. However, Brexit is no zero-sum game: Lower prices for corporate assets will be accompanied by a slump in domestic demand all over Europe, thus putting pressure on China's export-oriented industries.

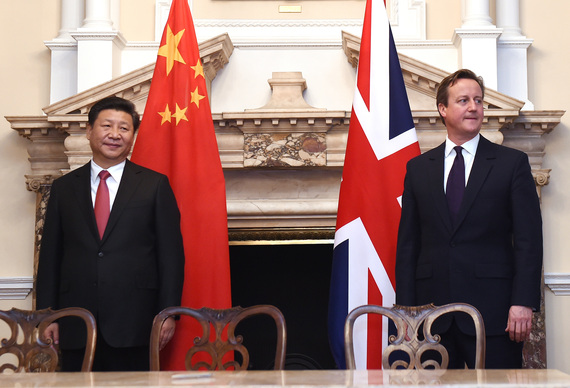

London's financial centre has until now enjoyed various policy privileges from Chinese authorities. In 2012, the City was the first place to receive permission to issue RMB-denominated bonds outside China. A year later, London was selected to become the first Western offshore trading hub for Chinese currency. As an offshore RMB centre, it also secured investment quota worth RMB 80 billion, beating regional Asian competitors such as Singapore. The Cameron administration's determination to build a 'golden era' of relations with China was an important driver behind this first-mover advantage. However, Beijing's motivation behind the preferential treatment of London has above all been self-serving in nature. The City has for decades serviced international financial markets, dating back to its pioneering role in developing European currency markets in the 1950s. Today, it accounts for 40 percent of global foreign exchange dealings, trading more dollars than New York and more euros than all other European markets combined. This dominant position has provided Beijing with the ideal platform to promote both RMB internationalisation and China's closer financial integration with the West.

Brexit changes that, by replacing stability with a collective of unknowns. Leaving the EU would almost certainly deprive UK-based financial firms of their passport to operate anywhere in the economic bloc. As a result, many China watchers have warned that Beijing risks losing its strategic access to Europe through Britain and with it the RMB's main gateway to European capital markets. However, there is an important difference between such perceptions and reality. Despite the scaremongering, Brexit is unlikely to wipe out London's location-specific advantages. Even outside the EU, the City will still retain its established expertise and distinct time zone advantage in foreign exchange trading. Frankfurt and Luxembourg also have RMB trading centres but do not share the same track record as London in currency markets. Brexit is therefore unlikely to change London's strategic importance for as an RMB gateway in the eyes of Chinese leaders.

If anything, China may use these conventional perceptions in the West to its advantage. The uncertainty over the UK's future provides an opportunity to play 'divide and conquer' with European countries over which money centres can secure policy favours from Beijing to expand their RMB business. China therefore stands to gain, not lose, political clout from Brexit.

As the terms and conditions of the UK's future access to the European Single Market will likely remain in limbo for some time, London will be eager to strengthen its ties with strategic partners outside the EU such as China. In this context, Britain may be more willing to make policy concessions, which gives China bargaining power. For example, a more divided Europe will allow Beijing to negotiate better investment conditions for its state-owned enterprises and financial institutions such as its sovereign wealth fund. This will be good news for Chinese investors. Brexit may provide them with new acquisition opportunities, as market access eases and asset prices drop. In the past, Chinese firms have often fallen on deaf ears, amid European fears over delivering critical technology into Chinese hands. Brexit will boost China's leverage when seeking to acquire Western technology and thus help make the leap toward industrial upgrading of its economy.

What may be a window of opportunity for Chinese investors will, however, be a headache for Chinese firms relying on exports. Falling prices on corporate assets reflect that domestic demand in Europe is weakening after the Leave vote. This is unlikely to change until a deal is struck between the UK and the EU, which is unlikely to come into force before the end of 2018. The resulting prolonged period of weak European demand will hurt Chinese manufacturers, since the EU is China's biggest trading partner, buying USD 385 billion of Chinese goods last year. This will put additional pressure on Chinese leaders who are already struggling to tackle the looming overcapacity problem in China's economy. Greater economic pains may therefore offset gains in political bargaining power. Brexit does not mean that China gains and Europe loses. Instead, the fate of Europe and the future of China are increasingly intertwined. As Europe's stumbles, so may China.