I recently found out Amm (Uncle) Salah, Cairo's famous tentmaker artisan, died some years ago, and that his daughter Mona carried on the tradition privately from her home until she moved away to Abu Dhabi.

It gave me a sinking feeling that another handicraft in Egypt was biting the dust due to unrest in the country, a suffering tourism industry, and decades-long competition from the Indian subcontinent.

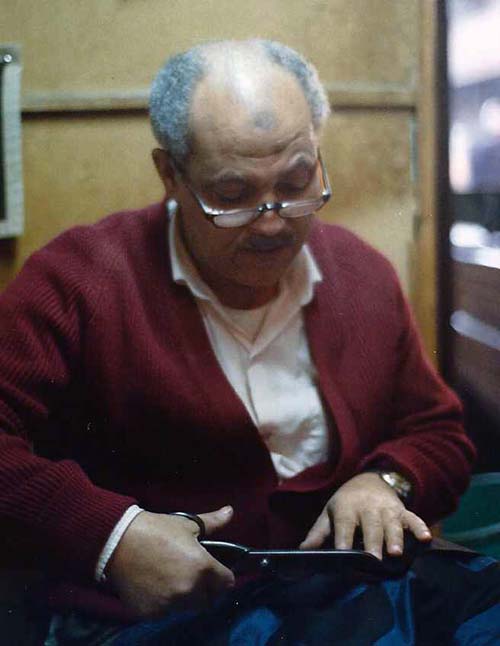

"Amm" Salah and vanishing Khayamiya trade (Abu-Fadil)

"Amm" Salah and vanishing Khayamiya trade (Abu-Fadil)

Even when I last saw Salah El Din Al-Awzi, one of Egypt's famous stitchmen who worked out of a small crowded shop and had gained international renown for his beautifully crafted products, the Khayamiya trade was on the slides.

The brightly colored ornamental appliqué tent decorations, bedspreads, pillowcases, bags, purses, and more, in the famous Khayamiya (tentmakers') district was slowly becoming a thing of the past.

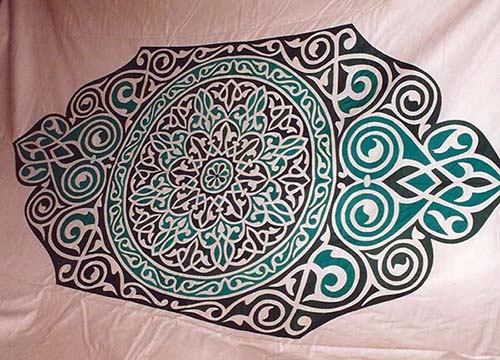

Part of a Khayamiya bedspread (Abu-Fadil)

Part of a Khayamiya bedspread (Abu-Fadil)

India and Pakistan were the main rivals as their workers were paid less and their fabric was cheaper - half the cost of Cairo craftsmen's outlays.

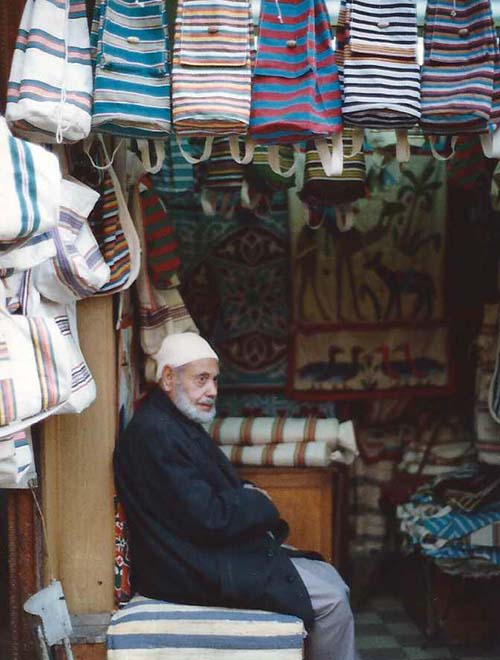

Most of the shops in the area not far from Bab Zuweila, in one of the Egyptian capital's historic areas, were small and packed.

Their owners a few years ago had become a rarity, a sharp contrast to the 1950s when the sheer numbers of craftsmen allowed them to have their own trade association.

When I visited Amm Salah, only 35 craftsmen remained in all of Egypt to thread their needles into the Khayamiya's internationally sought masterpieces of intricate cloth mosaics, Islamic patterns, pharaonic motifs, and occasional modern designs.

Crowded Khayamiya street shop (Abu-Fadil)

Crowded Khayamiya street shop (Abu-Fadil)

Slightly over 100 workers manned the machines that made regular tents used by customers such as the Egyptian army and police force, boy scouts, adventure seekers, and oil companies exploring the Middle East's many deserts.

As recently as 2011, there were reports the tent making business had just about come to a halt.

It is believed the Khayamiya trade dates back to the days of the Mamluks who ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1517 AD.

According to popular legend, the Darb Al Ahmar (red road) where much of the trade was located was named after the bloody battles that resulted from Mamluk massacres during long forgotten battles.

Younger Egyptians seeking college degrees, better paying jobs, and more favorable conditions shunned the Khayamiya. The work is tedious and backbreaking in those narrow, dusty alleyways.

Some pieces bought to decorate the interiors of homes, banks, and hotel conference rooms measured 100 square meters (1,076 square feet). Every time I saw them on display, I wondered how long it took to produce them.

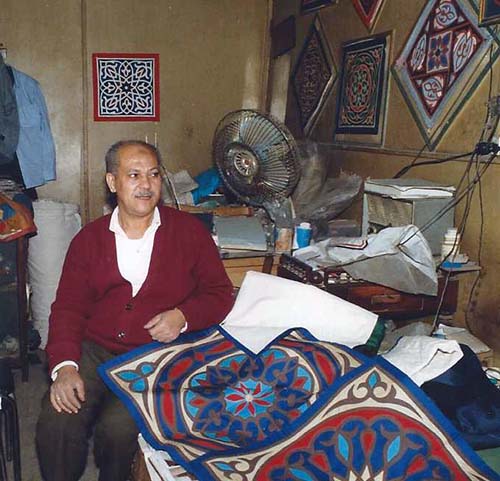

Floor pillow can seat two (Abu-Fadil)

Floor pillow can seat two (Abu-Fadil)

One worker told me a Saudi Arabian visitor had a dome (similar to a mosque) in his house fitted with a Khayamiya spread made up of 24 individual pieces, each measuring four by three meters (about 13 by 10 feet).

The layered navy, turquoise, green and white segments took several weeks to make. The customer then had the craftsman flown to Saudi Arabia to erect the piece.

The double burden of cheap imports - the craftsmen's worst nightmare - and rising demand for their beautiful products prevented old timers from passing on their skills and training to any interested young apprentices. There was never enough time.

The demand kept Al-Awzy inundated with orders from Egyptians and foreigners.

He used to sit crossed-legged atop a stoop, his fast needlework accompanied by a staccato recollection of the multicolored pieces he'd produced since the age of six when neighbors inspired him to become a Khayamiya man.

Al-Awzy's two brothers helped out with smaller orders of pillowcases and wall hangings popular with Western tourists, while he filled out requests for bigger projects.

The grey-haired stitcher preferred working with the most expensive fabrics like satin and silk. He said they were more beautiful, lasted longer, and didn't run when they were washed.

Salah El Din Al-Awzi liked working with satin and silk (Abu-Fadil)

Salah El Din Al-Awzi liked working with satin and silk (Abu-Fadil)

The finished product was always taken to a "makwagi" (an ironing/pressing shop) down the street where a huge antique foot-operated iron pressed out the wrinkles. It was a sight to behold.

Al-Awzy's craftsmanship was officially recognized by Egypt's Ministry of Culture back then, which awarded him a medal of appreciation.

But he felt the government was obligated to do more than just hand out awards. He wanted it to ensure the craft survived long after he was gone.