It wasn't easy being Chinese American in the early days. From exclusionary laws to the racist caricatures that dotted newspaper comic pages, America wasn't exactly laying down the welcome mat.

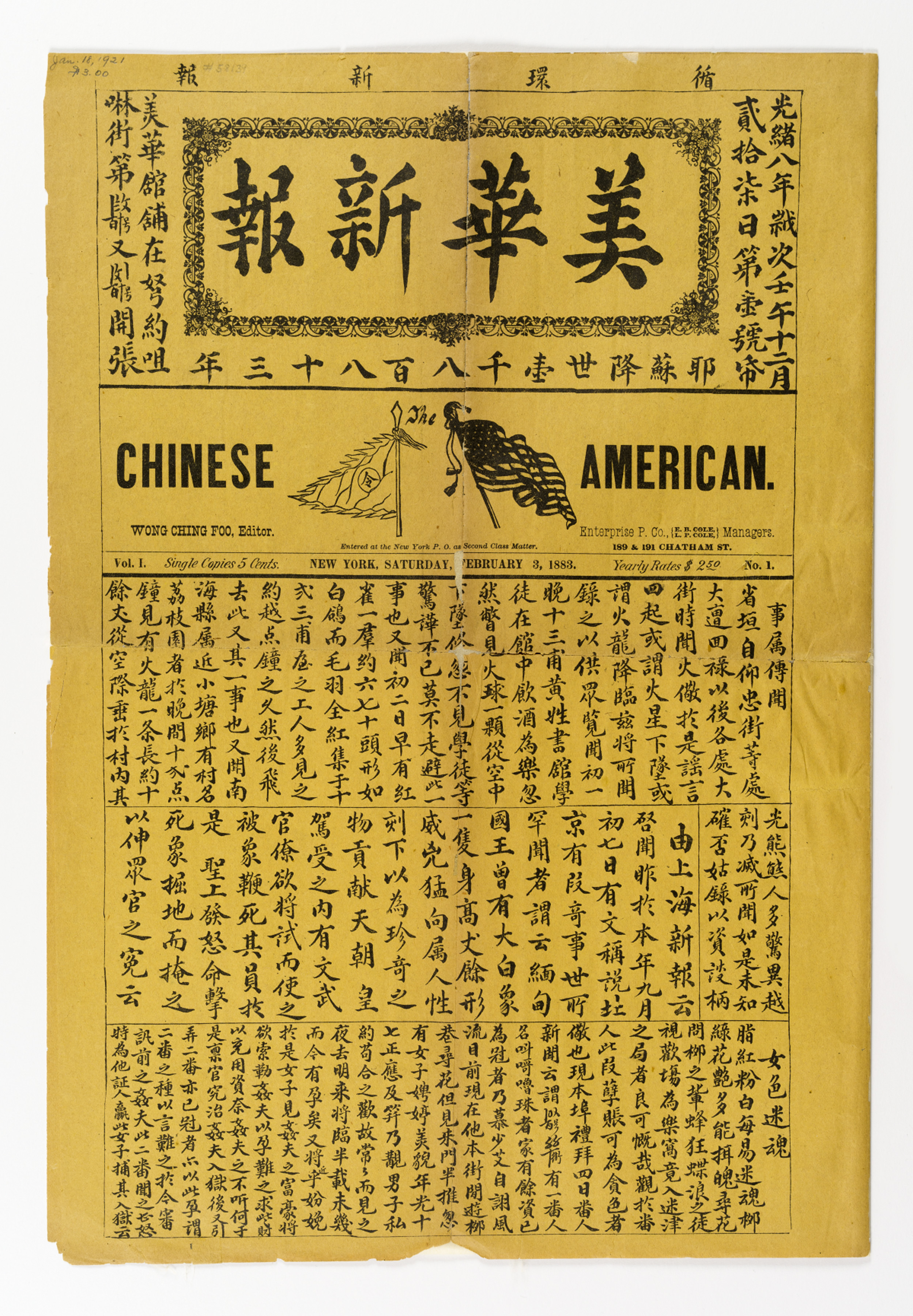

And yet, there were success stories. The Chinese American, a newspaper founded by the activist and journalist Wong Chin Foo, hit stands before the end of the 19th century. The actress Anna May Wong, born in Los Angeles to Chinese parents, beat the odds and wound up starring in silent films a few decades later.

Some died too young to become known, like the World War II fighter pilot below. Guess which side Hazel Ying Lee flew for:

Lee, on the right in the 1932 photo above, joined the U.S. Women Airforce Service Pilots and flew planes to warfront embarkation points. She died in a plane crash in 1944. Courtesy of Frances M. Tong, Museum of Chinese in America Collection.

We may not read about them in junior high school, but Anna May Wong, Wong Chin Foo, and Hazel Ying Lee are part of a great American saga. This fall, an exhibit in New York will attempt to tell it, through historic documents, maps, artworks, artifacts, and ephemera. Of the more than 200 items displayed in "Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion" many belong to the collection of the New York Historical Society, whose building will house the exhibit. Other sources include private collectors, various museums and historical societies, as well as the Library of Congress.

It's an understatement to call the effort a long time coming. In a press release emailed to HuffPost, Historical Society president Louise Mirrer describes the enormity of the imbalance at play. Consider that the first Chinese immigrants arrived on U.S. soil at the same time as the first Irish. Their impact over more than two hundred years "has been extraordinary," Mirrer says, "and yet its story is little or entirely unknown."

And yet it's a quintessentially American one. Take the rise of Joyce Chen. An émigré from Shanghai, she opened what would become a popular Mandarin-style restaurant in Cambridge, Mass, in 1958. Her reputation and subsequent cookbook led to a nationally televised cooking show -- the first TV series with an Asian host -- and her own Chinese cookware line.

Joyce Chen, pictured on set. Private Collection. © WGBH Educational Foundation.

These early accomplishments happened despite landmark barriers. Among them was the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, "the nation's first-ever exclusionary immigration policy," Mirrer writes.

At its worst, the law took advantage of poor Chinese laborers, allowing them entry without naturalization. At its best, it treated Chinese Americans like criminals, demanding they register their identity with the government (the only other Americans subject to the rule were, in fact, criminals).

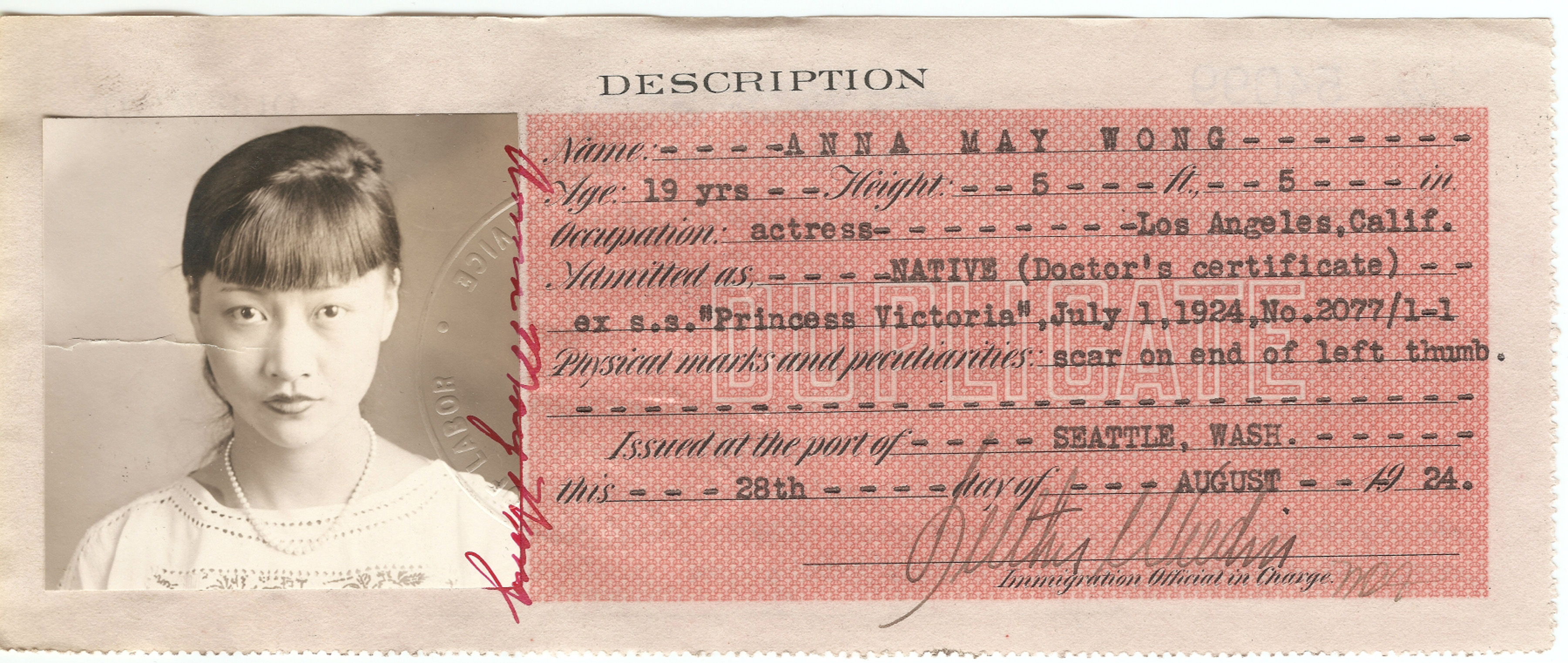

Even movie stars were subject to the law. Above, the government-issued identification card for Anna May Wong, the silent film actress. Starting in 1909, Chinese entering or residing in the U.S. were required to carry such ID at all times. National Archives at San Francisco.

If it all sounds a little familiar -- calling to mind modern border state politics -- that's not by accident. Mirrer identifies the exhibit's crux as a concept we can't seem to agree on: "What it means to be American."

For more images of items from Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion , scroll down. All captions and photos courtesy the New York Historical Society.

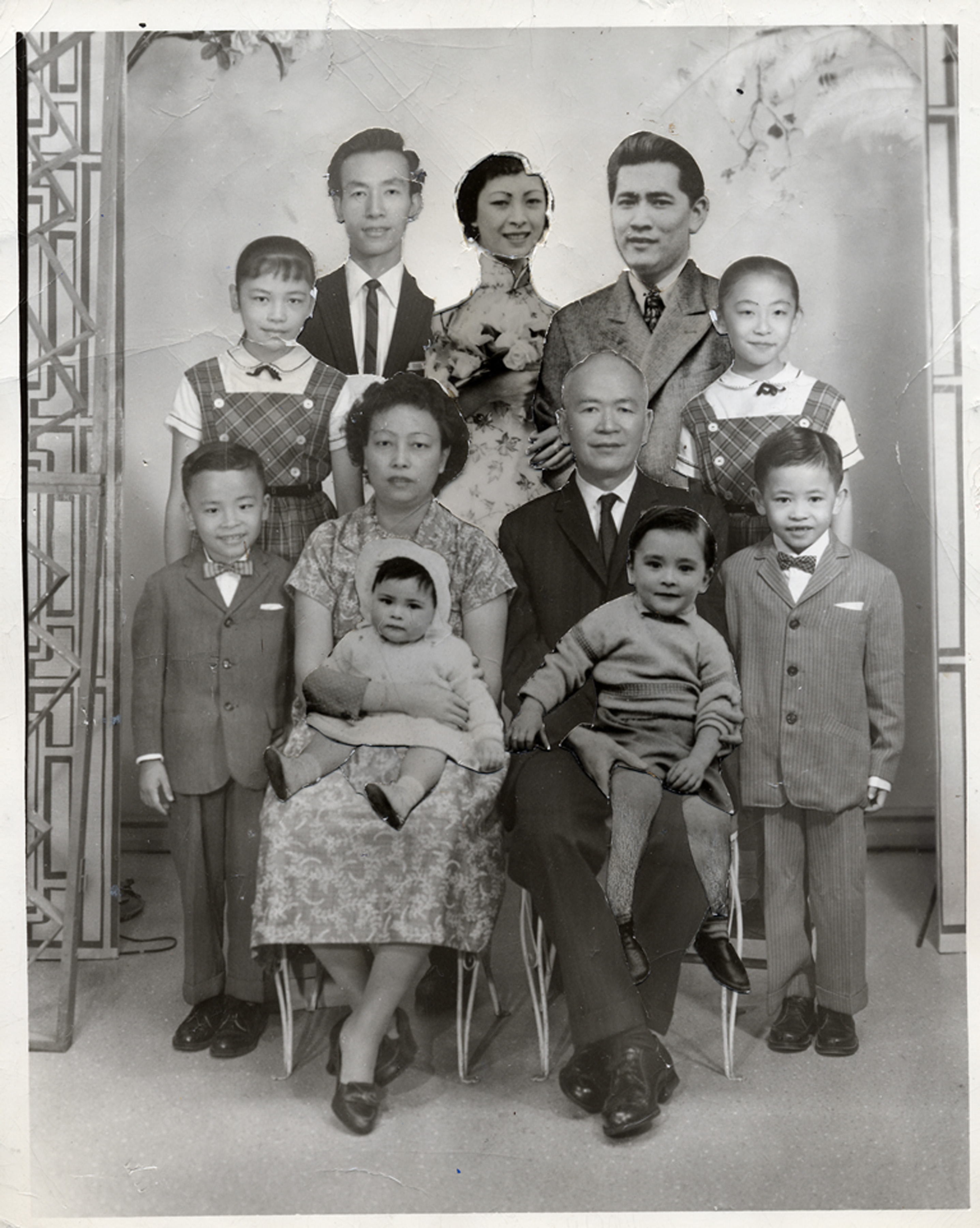

Adapting to the immigration laws that kept them apart, a local photography studio helped the Low family of New York create an impossible family portrait in 1961, by pasting in the faces of missing relatives. Courtesy of Museum of Chinese in America Collection.

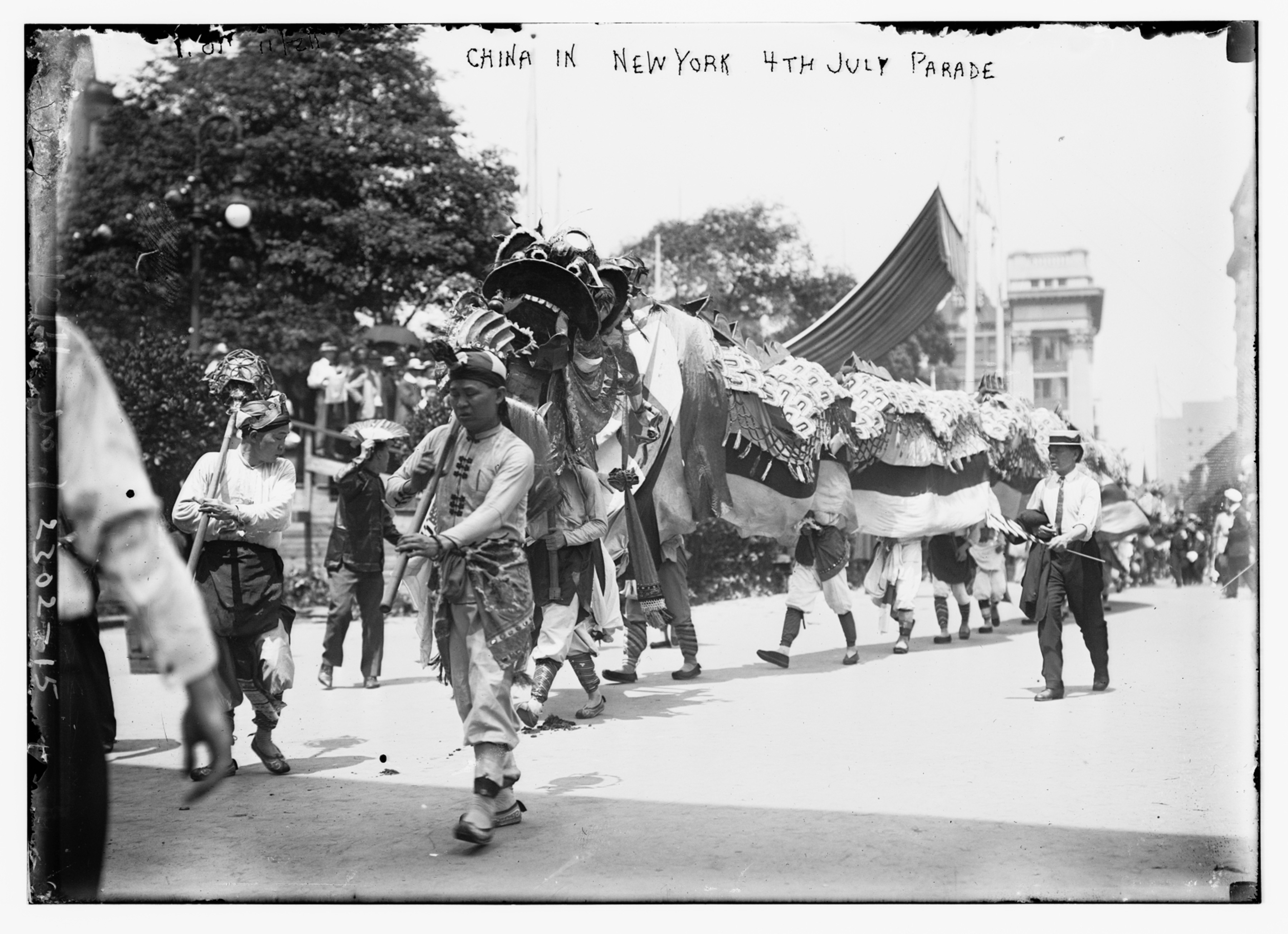

The large and prosperous community of Chinese residents in Marysville, California acquired this ceremonial dragon from China in the 1880s. “Moo Lung” appeared in parades and celebrations nationwide, including the July 4th, 1911 “Parade of Nations” in New York City. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

This 1950 watercolor by artist Jake Lee depicts Chinese laborers laying the transcontinental railroad track through the Sierra Nevada mountains, a pivotal project in the development of America. Courtesy of Chinese Historical Society of America.

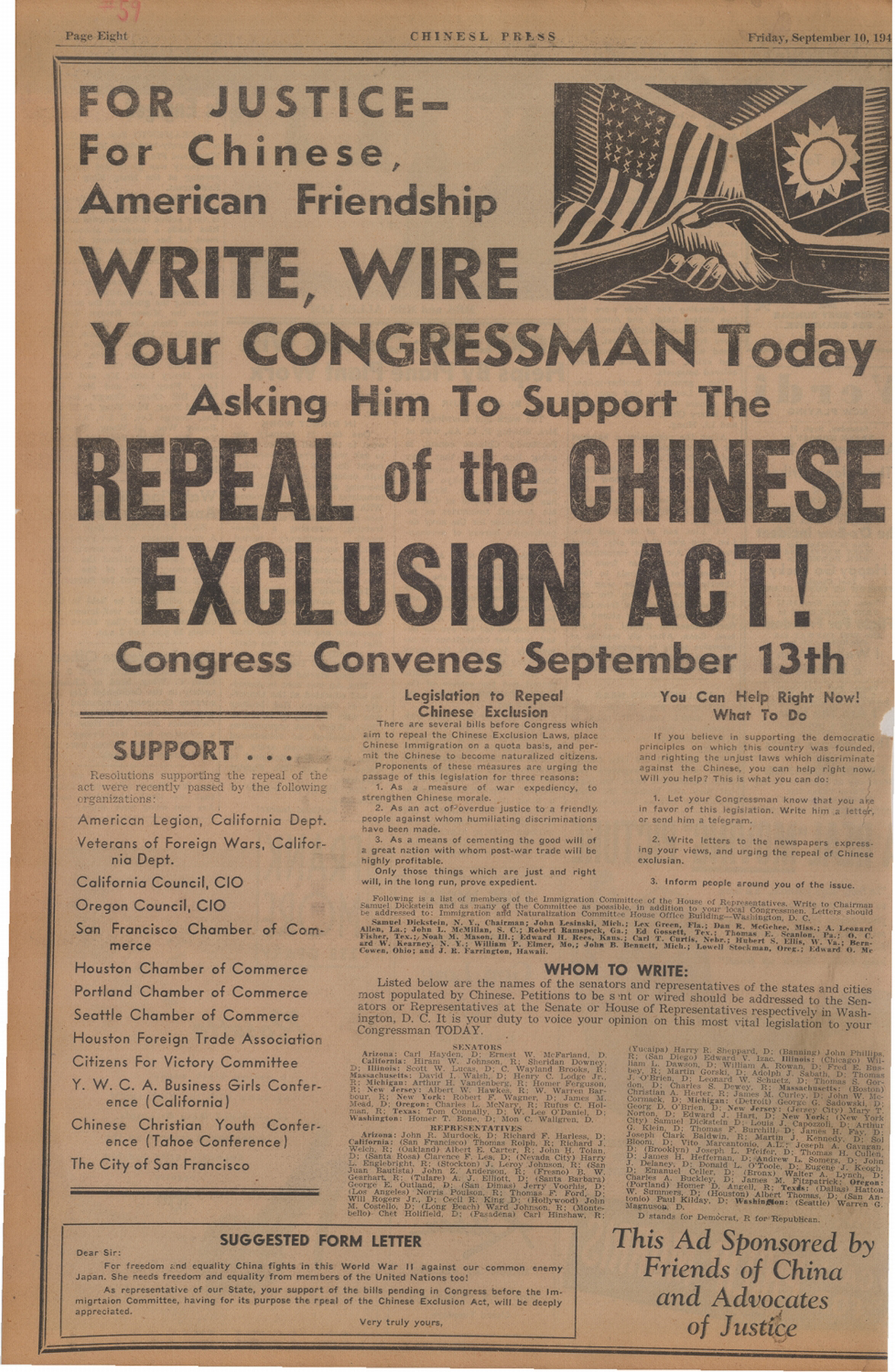

During WWII, Chinese Americans and their supporters petitioned Congress to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act. The 60-year statute was overturned in 1943, the year this ad was printed in the publication Chinese Press. However, Chinese immigration remained subject to severe quotas. Courtesy of Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA).

American-born Chinese youth gravitated to the Ging Hawk Club, which began in the 1930s as a YWCA-affiliated group. The photo above was snapped during a Thanksgiving at the Hotel Sheraton in New York City, sometime between 1933 and 1952. Courtesy of Alice Lee Chun, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection.

More than 200 years old, this fan depicts the Empress of China—the first American merchant vessel to trade with China. The ship departed from New York harbor in 1784 and returned the following year, laden with porcelains, silks, and teas. Courtesy of the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection.

Activist Wong Chin Foo published this newspaper, entitled Chinese American, in New York in 1883—possibly the first public use of the term “Chinese American.” In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, Wong intended the title as an assertion of identity and a challenge to anti-Chinese sentiment. Chinese American, 1883. New-York Historical Society.