Accidental pollution? Sure, s**t happens. But what about intentional pollution?

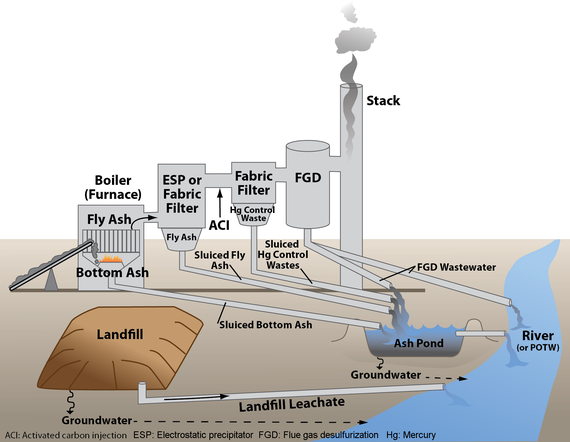

When we think of electric power plants and pollution, we often think of air pollution and climate change, and especially when it comes to coal-fired power plants. But power plants are also huge polluters of our waterways -- our streams, rivers, and lakes. In fact the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that

"Steam electric power plants contribute over half of all toxic pollutants discharged to surface waters by all industrial categories currently regulated in the United States under the Clean Water Act."

Not only that. It’s also estimated [pdf] that of all the country’s surface waters that receive power plant discharges

- 25 percent are impaired for a pollutant that is discharged by the plant and

- 38 percent of surface waters are under a fish advisory for a pollutant associated with combustion wastewater.

The sources of that pollution are myriad. Our topic for today is the flow of pollutants from coal ash ponds.

Catastrophic Failure of a Coal Ash Pond: Outrage, Calls for Action, and Then...?

Pollution from coal ash ponds has been front and center in the news of late. Especially in North Carolina where the failure of two ponds operated by Duke Energy sent some 30,000 to 39,000 tons of highly toxic slurry into the Dan River. (See more here and here.)

The last time coal ash reached such a high level of notoriety was probably back in December 2008 when a pond at the Tennessee Valley Authority's Kingston Fossil Plant in Harriman, Tennessee, ruptured, spewing more than a billion gallons of toxic ash into the Emory and Clinch Rivers and surrounding areas.

Catastrophic failures like those just cited have focused the American public's attention on the problem of coal ash for a time. And calls for reform have followed. The Tennessee spill was so bad that even before she officially became EPA administrator, Lisa Jackson promised to tackle coal ash regulations to prevent such spills from recurring (details in previous post). The current crisis in North Carolina has spurred public outcry and protests and investigations into possible malfeasance and corruption.

But unfortunately, crises don't necessarily lend themselves to effective rulemaking -- often a new crisis erupts, turning eyes elsewhere and causing the fervor for reform to fade. A case in point: today, more than five years after the Tennessee spill, we still await EPA's promised new regulations.It will be interesting to see if all the outrage in the Tar Heel State is anything more than political posturing that will fade as soon as North Carolinians become focused on the next crisis.

Intentionally Dumping Pollution -- Where's the Outrage?

While catastrophic failures of coal ash ponds can grab headlines and attention in a powerful way, there are other pathways for power companies to douse our waterways with pollution that gets far less attention, but at our own folly. Here are two.

When Rules Are Insufficient

Most coal ash ponds are not forever sanctuaries of pollution that never gets released into our waterways. Quite the contrary. The vast majority have permits that allow them to discharge their wastewater under specific conditions and limitations. In "Closing the Floodgates" [pdf], a joint report by the Environmental Integrity Project, Sierra Club, Clean Water Action, Earthjustice and the Waterkeeper Alliance, it is estimated that "at least 274 of the 386 coal plants [reviewed for the report] discharge coal ash and/or scrubber wastewater" to waterways.

Here's one of the problems: The rules governing wastewater discharges from utilities to surface waters -- last updated in 1982 -- are outdated. What's more, while these rules are designed to limit the amount of solid or particulate material that can be released into waterways, the bad stuff in coal ash is not just solid.

With the advent of air pollution controls, the coal ash wastestream now contains growing amounts of soluble and often toxic pollutants such as arsenic, selenium and mercury. Because they are dissolved, settling action does nothing to remove them. And while state permits often set maximum allowable levels of some soluble toxic pollutants in the wastewater that can be released, these regulations are often lax, and for some toxins the regulations are nonexistent. For example, according to "Closing the Floodgates":

"Of the 274 power plants in this review that discharge coal ash or scrubber wastewater, only 86 had at least one limit on arsenic, boron, cadmium, lead, mercury, and selenium discharges."

So while power companies and state agencies often point to the existence of permits as evidence that pollution from coal ash ponds is carefully regulated (see here for example), the wastewater from most coal ash ponds that is legally discharged into our rivers and streams is almost certainly loaded with a cocktail of dissolved heavy metals and other toxic substances.

There may be good news of the horizon. EPA is expected to finalize rules that would establish the first federal limits on the levels of toxic metals in wastewater. Just when that will happen remains to be seen. A deadline of May 2014 has been pushed back [pdf] indefinitely.

When Rules Allow Pollution

As lax as most permits may be for coal ash pond discharges, they at least provide some limitation on what can be released. But even this weak system of pollution control has a safety valve ever at the ready for power companies to exploit. Simply put, the safety valve allows power companies to intentionally divert wastewater from a coal ash pond -- directly into our rivers and streams.

I first learned about this from a New York Times story that reported on a system set up by Duke Energy that pumped wastewater from two coal ash ponds directly into canals that feed the Cape Fear River. The discharge, which was discovered by the Waterkeeper Alliance at a plant near Moncure, North Carolina, about 25 miles outside of Raleigh, has apparently been taking place since last fall.

While I, and perhaps you, might be inclined to refer to the practice of intentionally diverting wastewater into surface waters as “dumping pollution,” regulators prefer a kinder, gentler term -- a euphemism sterile enough to make George Carlin cringe. Instead of dumping, regulators call it a “bypass” [pdf] -- "an intentional diversion of wastestreams from any portion of a treatment facility."

Now, the specific rules under which a plant might exercise a bypass are governed by the permitting state. However, EPA also provides rules and guidelines [pdf] for these permits. Bypasses, according to federal government, are allowed under such circumstances as "to prevent loss of life" and when there are "no feasible alternatives to the bypass." However, the regulations are qualified such that

"this condition is not satisfied if adequate back-up equipment should have been installed in the exercise of reasonable engineering judgment to prevent a bypass which occurred during normal periods of equipment downtime or preventive maintenance."

With words like "feasible" and "reasonable" these guidelines are probably intentionally vague, giving the states some latitude to interpret and enforce them. It would appear that some states have given power companies lots of wiggle room to justify their dumping.

For example in the case of pumping as much as 61 million gallons of coal ash wastewater up and over the pond embankment into a canal draining into the Cape Fear River, Duke Energy claims that the discharge was part of "routine maintenance." Now, it might just be me, but an action that lasts for six months would seem to have had time to install "adequate backup."

In another case of dumping, this one by Louisville Gas and Electric into the Ohio River from 1993 to the present, the Kentucky Division of Water claims the discharges are "legally permitted." And how's this for double speak:

"While the permit ... describe[s] [i.e., restricts] the direct discharge ... to the Ohio River as 'occasional', the permit effluent requirements do not restrict the frequency of the discharge. Consequently, there is no violation of the permit for frequency of discharge."

Those are two documented cases of using the bypass rule to circumvent regulations intended to protect our waterways from direct toxic discharges. How many more of them are there I wonder? Whenever there is talk of tightening federal regulations of coal ash disposal, for example by treating it as a hazardous substance, the coal industry promptly calls foul, claiming there is a "war on coal." But with all the pollution from coal ash fouling our rivers and streams one has to wonder who's the warrior and who's the victim.

____________________________

End Notes

There are approximately 676 coal ash ponds across the country in 41 states. (See map of coal ash waste sites.) Dozens of toxic metals such as arsenic, lead and selenium are found in coal ash. (Details here [pdf].) Currently there are no federal rules on how to dispose of this waste although one has been promised by the end of the year. Some of the ponds are unlined and some are associated with impaired groundwater and surface water. ↩

Interestingly, this month TVA announced it has just finally finished a new containment wall. After five years and a cost of more than $1 billion. Cleanup is still ongoing.↩

While the leak at both plants appears to be the fault of the utility, circumstances surrounding the leak at the Dan River plant are different because the federal government had cracked down, in an agonizingly slow way, on potentially risky coal ash containment ponds. And the Dan River was one of the watch list.↩

This is why coal ash ponds are often referred to as settling ponds -- they are ponds where solid pollutants settle out before the water is released.↩

Keep up with TheGreenGrok | Find us on Facebook