This is the eighth installment of XX Chromosocial: Women Artists Cross the Homosocial Divide. Some of the concepts used in this post, such as "the homosocial," are introduced and elaborated in the first and second installments. Links to all seven prior installments are listed at the end of this article.

This commentary could prove lethal to the humor in Mimi Smith's and Susan Bee's art. Or so we might expect, were their humor based in the kind of societal repression informing conventional comedy. It is customary that explaining a joke--which entails exposing a deeply engrained prejudice in favor of one societal and often political order's repression of another--hinders the comic effect. A conventional joke falls flat with the mere intent to support or to scrutinize it. And then there is the audience embarrassment that ensues when the complicity of the audience is exposed for sharing in the satisfaction gained at the expense of the joke's target--the repressed subject. Even the element of timing, so essential to a joke or comic scene, depends on the audience's complicity with the comic's perpetuation of repression without scrutiny--complicity that reinforces the audience's suspension of disbelief, tolerance of inanity, even an unrealistic disregard for the absurd. Such collective conformity makes a successful joke entirely antithetical to analysis and criticism. For in analysis and criticism, we ferret out the social codes underpinning humor, thereby poisoning the very humor we admire--or detest. And all of this is because a sense of humor by convention can only be shared with a community that consciously or unconsciously recognizes and upholds the dominant code of societal repression referenced in a joke or comic skit.

But the humor employed by Mimi Smith and Susan Bee isn't conventional. In fact it is more an antihumor they indulge. Not anti in being against humor, but in being against a repression that has traditionally been the source of much mainstream humor. In fact, theirs is a humor that consistently taps not repression, but the repression of repression. The repression of women, to be precise. It is an antihumor that turns the tables on the traditional repressors of women, the profiteers of male homosocial supremacy. Unlike the humor of the bigot that reinforces cultural and class divisions, an airing of the structural and social conditions of the humor supporting and informing an activist art, such as Smith's and Bee's work, rewards us with a social and political subversion--or at least a gratification that comes in imagining that subversion at work. By now it must be obvious that I'm referring to the feminist humor that has informed the art of Mimi Smith since the mid-1960s, and the art of Susan Bee since the early 1980s. Smith's and Bee's art makes us laugh at the idiocy (the fears and myths) informing the male homosocial codes legislating women's repression, while asserting a feminist blockage of the conventional male humor perpetuating the history of women's persecution and enforcing a code of female homosocial norms in sync with male supremacy.

It is surprising that we don't see more of this kind of activist humor in the art world. It certainly is well digested by the liberal Left in such long-running and scathing mainstream entertainments as Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show, and The Colbert Report. And there is every reason to expect a more sophisticated, reflexive humor historically operative in art, at least since the far Left came face to face with its own proclivity for repression in the gulags and purges of the last century. No doubt the Old Left was unwilling to study the two-sided humor of Aristophanes, Shakespeare and Molière that exposed social repressions--artists they denounced for being bourgeois. But then the Old Left was largely deferential to the serious and explicit moralizing and propagandistic agendas of agitprop.

On the other hand, the literature of philosophy and psychology has both long supported humor as political strategy, given that Aristotle conceived of comedy as a powerful form of catharsis, and Freud excavated evidence of the mind confirming that the humor surfacing in dreams, double entendres and jokes evolved as an outlet for desires suppressed for millennia by a succession of authorities. Of course, since all these advocates of humor were men, it goes beyond expectation that any one of them might go so far as to set humor to work challenging male supremacy--though Shakespeare, who wrote in the reign of a powerful and attentive queen, comes nearest in his comic crossgenderings. Whether or not mainstream audiences understand that comedic expression exposes the proscribed drives of the body politic, today's audience for art should now be adequately drilled by feminism to understand that the history, pedagogy and marketing of the arts are largely shaped by male homosocial codes repressive to both women and men.

I'm citing the male homosocial imperative introduced to sex and gender theory by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick rather than settling for the more general and amorphous concept of patriarchy. For patriarchy insufficiently accounts for the mysterious solidarity that binds men with men. Similarly, the notion of matriarchy can obscure the perpetuation of male codes underpinning women's homosocial bonding by faciliating women with a modest social mobility that too often obscures the larger diminishment of women's political and social efficacy in affairs requiring contact and collaboration with men. In looking back on the art of history, we can find clearly depicted evidence to support the view that art has been instrumental in fortifying what in the last few decades has become conceptualized as the homosocial divide of civilization. By this I mean the cultural and geopolitical halving of humankind based not on gender difference alone--that is not by chromosomal determination--but as well by the presumed non-sexual, yet no less compelling, same-sex attractions cementing the alliances constricting power and privilege according to a culture's dominant XY (male) or XX (female) chromosome preference. In simpler terms, today's art is consciously being informed by what it always unconsciously reflected: the near-compulsory comfort found by men socializing exclusively with men and women exclusively with women.

Amid this steep social repression of individual desire, humor has phased in and out as an acceptable expression of the repressed urges of individuals and collectives, depending on the predispositions of governments. But it matters not whether a government is liberally tolerant or stringently suppressive of humor. In all cases, humor acts as an index of those desires enjoyed and proscribed by the social authority. And we not only find those indexes to humor best defined within the homosocial enclaves of men and of women, we also find that the humor of repression comes nakedly into play with the increase of defensively misogynistic jokes and allusions by men. In fact, the humor of men and women steeply conditioned by male homosocial codes are likely to provide the clearest evidence of how inclined a society is or how resistant it will be, to the rise of feminist activism. And what is most evident today, is that in the West, the art of women has elicited some of the most nervously, even desperately, misogynist humor by men in response to the recognition that the male homosocial divide is actively being leveled and crossed by women.

Humor may not come to mind easily when we think of significant feminist artistic activism. But perhaps it should, as much of women's art made since Freud has not been void of scandalous and double-sided humor. Georgia O'Keeffe, Meret Oppenheim, Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varos, Niki de Saint Phalle, Marisol Escobar, Carolee Schneemann, Yayoi Kusama, Eleanor Antin, Adrian Piper, Lynda Benglis, Louise Bourgeois--all have at sometime or other made humor attendant to the issues of sexuality and gender in their work. But except for a few noteworthy exceptions--Cindy Sherman's social mimicry poking fun at the social and political roles and signage imposed on women; Deborah Kass's Warhol Project and Feel Good Paintings that simultaneously make fun of and admire male homosocial artistry; Kara Walker's scathing depictions of sexual depravations heaped on African slaves by whites in the antebellum South; and Kathe Burkhart's Liz Taylor paintings that equate all that was good and bad in the life of the superstar icon with Western sexual politics--surprising little compelling and sustained critical humor has been paid to the sex and gender coding informing the global recognition of male supremacy. Which is why I wish to now draw increased attention to the art of Mimi Smith and Susan Bee for their satirical exposure of the women's homosocial codes that were imposed on them by men.

Only humor can replace humor. For humor is not only the psychological site of the self which has been homosocially conditioned to tolerate and approve the suppression of human rights and desires. Humor is also the first site of the refusal of the censor. We see this is realized fearfully by that most autocratic of philosophers, Plato, who in advocating tight control of the state's critics, admonishes, in Laws, "We shall enjoin that [comedic] representations be left to slaves or hired aliens, and that they receive no serious consideration whatsoever. No free person, whether woman or man, shall be found taking lessons in them."

Were Plato alive today, he would no doubt suppress the humor affording a new women's homosocial code with the most likely tropes for penetrating the consciousness of mainstream women and men. Which is why women's humor, with its own ascending, feminist-homosocial codes, is required to supplant those women's homosocial codes that for millennia had been legislated by men. The struggles facing women activists should not deter feminist humor, given that humor functions most economically and existentially in times of crisis. The more extreme the pressure, the greater the loss, the more urgently and purposely humor functions; the more deeply humor assuages unconscious impulses. It is at the bottoming out of the individual will that we locate the humor that succors the human core, the individual that is prior to desire and code--the self that can laugh at all that we and others should never befall. This is the human center at which Sartre and de Beauvoir located the birth of resistance, the rebel who socially disconnects from the stringent codes used to censor desires and legislate behaviors with the myth of sublimating the individual's will for the collective good.

Mimi Smith and Susan Bee show an understanding that the collective good need not be achieved at the expense of the individual will, that feminist art can be greatly facilitated by humor. And since Smith and Bee deploy that humor while routing out the codes that buttress patriarchal law and morality within both male and female homosocieties, their art can also be seen as leveling the homosocial divide by eroding the sharp differentiations defining gender and sexuality. Through the humor of Smith and Bee we come to see the feminist confrontation of the absurd--that interface at which the external world's indifference to the human will obstructs gratification of individual and collective desire. Comedy in their hands illuminates the feminist confrontation with the absurdity of male supremacy by highlighting the male-homosocial codes attaching and ordaining sexual and gender values and identities to a spectrum of behaviors that have not so much evolved through nature as been enforced by oligarchs--by both patriarchies and matriarchies--centuries, even millennia removed from us, yet conducting our conscious and unconscious behaviors today no less.

Together the work by these artists have compelled me to consider that humor is a vital critical process in the leveling of the homosocial divide while providing a bridge for both men and women seeking departure from the codes of the archaic and oppressive homosocieties that still dominate the ideological and commercial shaping of sex and gender codes. At the very least, Smith and Bee make art that assures us that feminist art possesses the self-assurance that comes with the vision of the future longevity and spread of feminist cultural codification. But then Mimi Smith and Susan Bee have for the last few decades demonstrated that feminist humor has nothing to lose by sketching an ironic, even self-deprecating caricature of the absurd sexual and gender codes that historically have been both imposed on women and assumed by them.

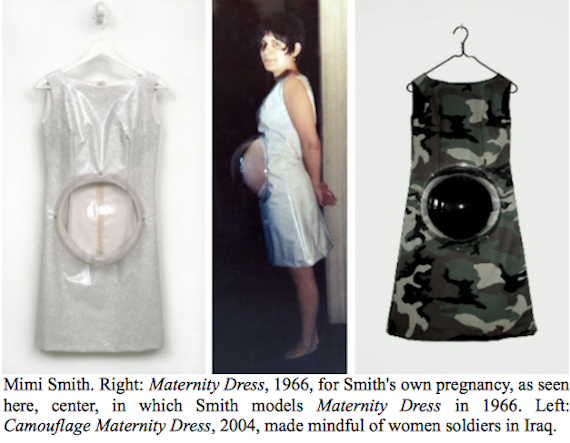

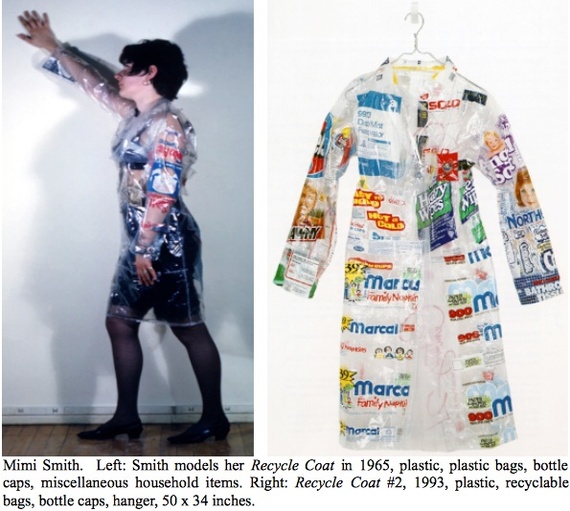

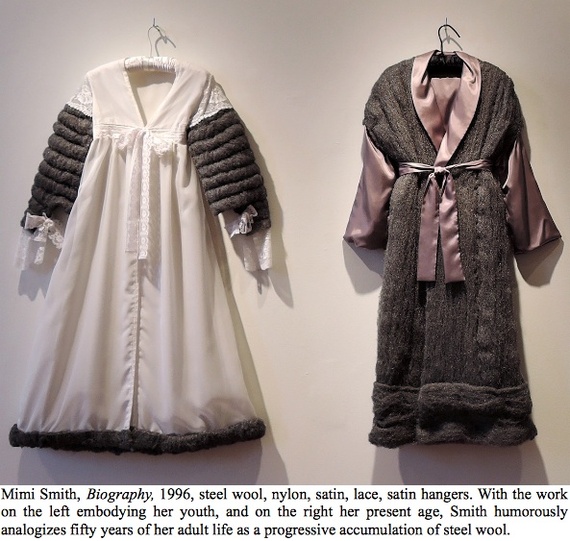

The history of sexual and gender coding indicted by both artists restricts itself to the recent past and present--a matter of the decades that the women have lived through. In Smith's case, the indictment unfolded in the present and personal tense, and only fifty years after it was begun can we see the continuous and persistent self-deprecation of her own conditioning as a woman informing her comically-exaggerated reconstructions of women's couture and leisure wear. Many of her clothing sculptures have been modeled on her own body, her needs, her life events--such as her pregnancy, her aging--though they can also be extrapolated as lampooning the sexual and moral codes restricting women's advancement for the sake of perpetuating the imperatives of male sexual gratification.

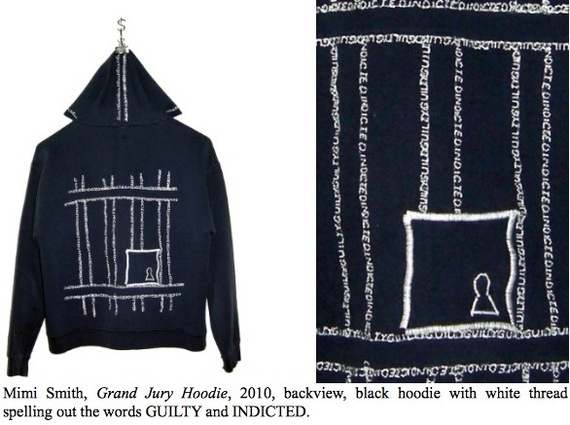

Smith couldn't have made a better choice than to scrutinize women's couture and the undergarments literally supporting it in the 1960s--given that women's fashion is both the most ubiquitous index to, and the most inhibiting harness of, the male sexual legislation of women. For five decades Smith evolved her lampoons in keeping with the fashions and political events of the day. Her work often departs from exceedingly personal circumstances--as with Maternity, a cocktail dress replete with transparent plastic bubble for her own yet-unborn baby in 1966--to evolve over the decades into the larger culture, as it did in 2004 with Camouflage Maternity Dress, made with women soldiers in Iraq in mind. Even in the less clearly biographical work, Smith's body can be perceived informing such zeitgeist icons as Girdle, hilariously made from rubber bath mats for women in their twenties (Smith's age) in 1966, to the more recent Grand Jury Hoodie in 2010, with its often deadly implications for people of color.

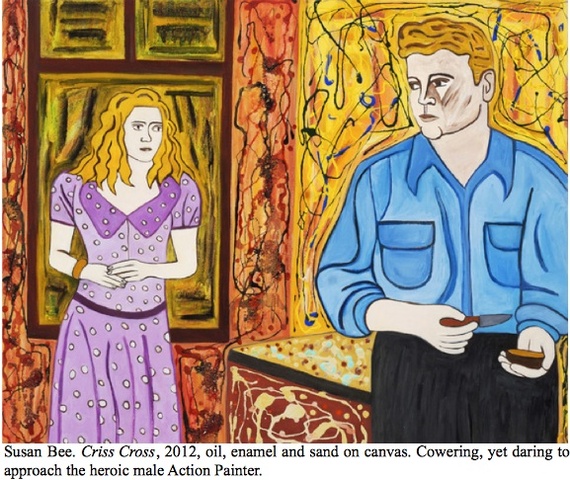

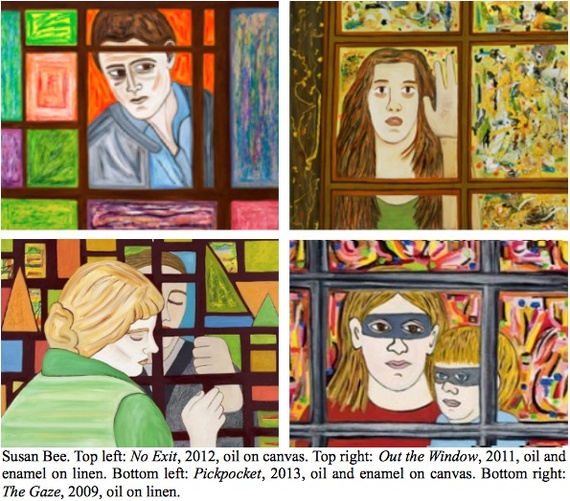

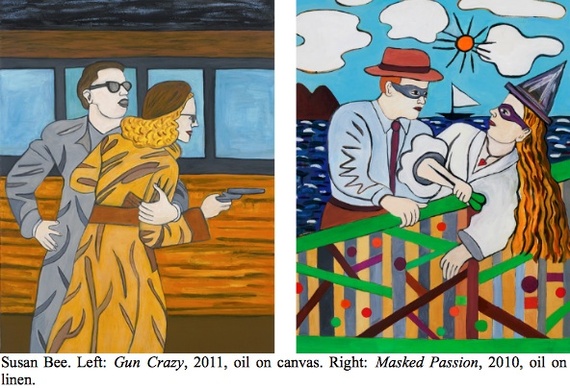

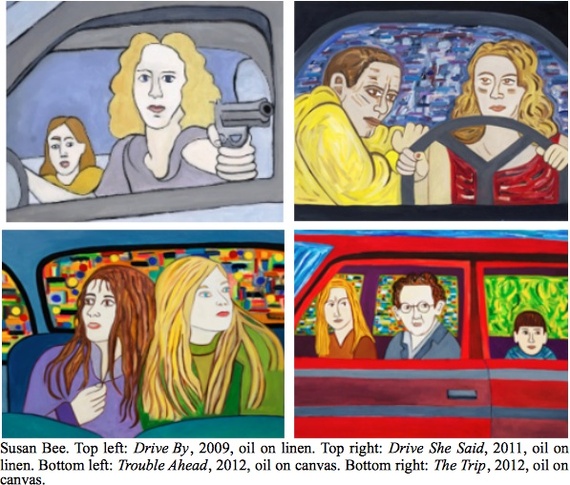

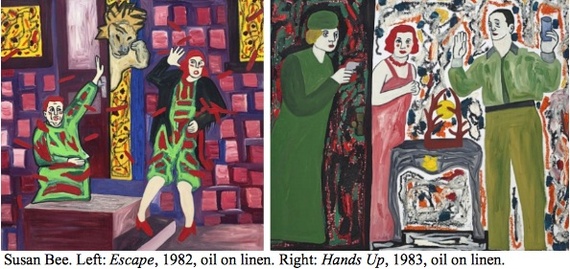

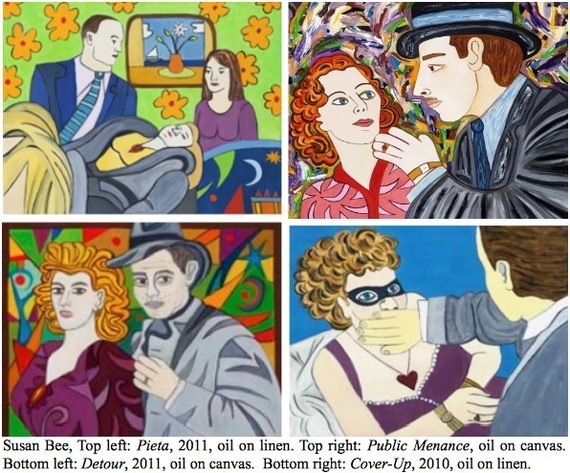

Since the early 1980s, Bee has similarly denoted popular culture in her evocation of vintage comics, film noir (Gun Crazy, Cover-Up) and women's melodramas (Pickpocket, Pieta) of the mid 20th century, but then slips in references to high modernist painting conveyed with interactive splatters and expressionist gestures that double as walls, skies and window views (Criss Cross, Hands Up). In the context of 21st-century feminism, Bee's paintings transform into a comedic, retrospective pictorial survey of the cliches and stereotypes that came out of the tensions erupting within the homosocial coding of women's prescribed behaviors and the frustrations that mounted as those codes collided with the increasing liberalism afforded women after the Second World War. We laugh today at the sight of the heartfelt longings of women on the verge of emancipation, yet still curtailed by their own divided psyches to conform to the codes of their mothers.

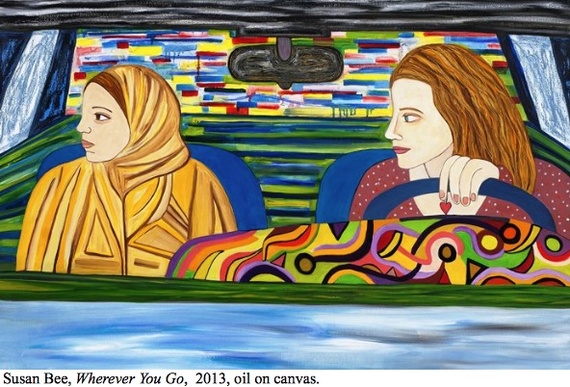

Women viewers of a certain generation may laugh at their former selves or their mothers and grandmothers. We all laugh at sight of the culture we came from, with women either peering through windows (Out the Window, The Gaze) and metal bars, perhaps in prison, but more likely restrained within some self-imposed exile. But Bee also depicts the alternative lifestyle of the day, the strong and capable woman driven to antisocial behaviors (Drive By, Drive She Said) for having no other socially prescribed outlet for her ambition or economic requirements. Claustrophobic interiors recur, particularly within cars (Trouble Ahead, The Trip) suggesting both repression and an aimless, fearful searching for a long-awaited destination, perhaps as a fugitive or outcast. Women in particular are pictured as if carrying about them a nervous anticipation reminiscent of Thelma and Louise (Wherever You Go). Others are seen being put in their place or taken advantage of by men (Public Menace, Detour), the best of which Bee adeptly surveys the codings of masculinity that have surged through comic books, Hollywood action flicks, and the overwhelmingly male-dominated mythos of avant-garde artists of the 1940s and 1950s.

What prompts us to laugh on first acquaintance with both artist's work gradually sustains within us as a reflection and criticism of the everyday homosocial codes (though we may intuit them more vaguely as conditionings) that inform traditional enclaves of men and women. Then, too, their humor is presupposed by a recognition that all humor is somehow informed by social repression. And with this realization we conceivably understand that the sustained humor informed by bigotry and ignorance can itself be made into the butt end of a joke by a truly democratic comic. This is what Smith and Bee do: take the absurd and archaically-informed bigotry and ignorance of male homosocial culture and transform it into a sign that comically exposes the misogyny being disseminated and perpetuated in the mainstream. Humor does accompany political emancipation, however much that emancipation requires a suppression of its own--the eradication of the very repression that a prior and maligning humor has historically presupposed.

This series has been written in tribute to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero and Sarah Charlesworth.

Parts 1 through 7 of "XX Chromosocial: Women Cross the Homosocial Divide" can be found at the underlined links below:

Part 1: Women's Hidden Homosocial Past, Shirin Neshat, Laila Essaydi, Deepa Mehta, Marina Abramovic, and Angela Ellsworth.

Part 2: Gender As Performance & Script, Yvonne Rainer, Sarah Charlesworth, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler.

Part 3: Women's Art of Renewal (Disseminating New Codes and Enculturations): Carrie Mae Weems, Vanessa Beecroft, Sharon Lockhart, Catherine Opie, and Lisa Yuskavage.

Part 4: From Victim to Victor, Women Turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out: Artemesia Gentileschi, Käthe Kollwitz, Frida Kahlo, Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Ana Mendieta, Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Janine Antoni, Kara Walker, and Sue Williams.

Part 5: Did Men Invent Art to Become Women? Must Women Become Men to Make Great Art? (Leveling the Gender Divide) Sherrie Levine, Deborah Kass, Collier Schorr, and Jenny Saville.

Part 6: Women's Mythopoetic Art: Going Back to Start, Heroically. Marina Abramovic, Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Mariko Mori, Shahzia Sikander, and Claudia Hart.

Part 7: Women Looking at Men Loving: Eve Sussman, Kathryn Bigelow and the Women Writers of Mad Men.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.