For such a storied vegetable, the pumpkin has a dull reputation in the United States. Except for a bit of excitement around Halloween and its proverbial presence on the Thanksgiving table, it's fairly dismissed. On the other hand, Italians, who grow more of them than Americans, love pumpkins far too much to smash them in the streets for a bit of fun.

Cucurbitaceae, the genus that includes pumpkins, squashes and edible gourds, has nourished people on nearly every continent for millennia. Although it is true that the Spaniards brought pumpkins and squashes to Spain along with other New World specimens, historical accounts from Apicius to Charlemagne place them on pre-Columbian tables throughout Europe. Of course, it was mostly the poor who ate them and other edibles from the plant world; only the higher classes ate meat with any regularity.

Pumpkins of Venice

Of all of Italy's gastronomically diverse 20 regions, none raises the pumpkin to such culinary heights as the Veneto, of which watery Venice with its 100 islands and 150 canals is the glittering fairy-tale capital. On the remote lagoon islands where the first settlers migrated from the outlying provinces in the fifth century to escape marauding barbarians, the inhabitants hunted waterfowl and small game, fished, harvested salt, and grew fruits and vegetables. Pumpkin, what the Venetians call zucca ("suca" in dialect), which lasted through the cold weather, kept the wolf from the door until spring.

The pumpkin -- marina di Chioggia (pronounced kee-ohj'-jah), also known as sea pumpkin, after its native town in the lagoon -- is by far the best I have tasted. Dense, flavorful and silky, it is hardly any wonder that so many delicious recipes have been derived from it.

Called "suca baruca" (warty pumpkin) in Venetian dialect, the slightly squashed sphere with gnarled, dark green skin and vibrant orange flesh is rich and sweet enough, once cooked, to eat as a confection. Once, vendors walked around the streets of Venice balancing wooden planks piled high with roasted pumpkin on their shoulders, hawking, "Suca baruca, suca baruca" to eager schoolchildren or anyone else wanting a sugary snack.

The "suca" criers are gone, replaced by souvenir peddlers, but Chioggia pumpkins have become universally loved in Italy and beyond, and vendors with their big golden wedges of pumpkin still ply the markets from the Rialto to Sicily. Mauro Stoppa, chef and skipper of the Eolo, a restored vintage flat-bottom sailing bragozzo, runs dining cruises on the lagoon and makes Chioggia's ancient signature dish, suca in saor, sweet-and-sour pumpkin, in his galley.

He salts slices of zucca in a colander as for eggplant to remove excess moisture. Next he dredges them in flour and fries them in olive oil until crisp. Then he smothers them in three alternating layers of thinly sliced and gently sautéed onions, sultanas, toasted pine nuts and white wine vinegar. He chills this mélange for several days before serving it as an appetizer. Each of the ingredients contributes to a perfect sweet-and-sour harmony, but of prime importance is the zucca, which alone provides the sweetness to balance the vinegar.

We could grow marina di Chioggia pumpkin in the United States commercially if there was a demand for it, though I imagine its sheer size would discourage the prospect of shipping it to market, whereupon it would have to be cut into smaller sections for selling. Still, all is not lost. Widely available, silky-textured butternut squash and the West Indian calabaza stand in nicely for sweet and savory dishes, and for pie filling.

Overall, the Cucurbitaceae family's bland and compact flesh makes these squash an ideal canvas for the savory and sweet creations the Italians cook. The blossoms are prepared in a variety of unusual ways, while the pulp is made into soups, Amarone-spiked pumpkin risottos, pumpkin tortelli, cappelletti and gnocchi, to name just a few dishes.

They can also be used in savory pumpkin tarts flecked with prosciutto, sweet versions with pumpkin-honey-candied orange filling and walnut-flour crust. One of my favorite recipes is one I grew up with, a colorful meeting of pumpkin (or squash), garlic slivers, black dry-cured Moroccan olives (if you've ever wondered what to do with these prune-like olives besides adding them to tagines, now you will know) and thyme.

Although my mother was born in Sardinia, when her mother died at a young age, she was sent to live in Rome with a family that retained a gifted Venetian cook. It's hard to know where this dish, redolent of garlic and tomato, came from, as it is more southern Italian in character than anything else. Perhaps it was my mother's own invention, but I can't help but wonder whether she wasn't struck with pumpkin love in that Venetian kitchen long ago.

In America, our Halloween jack-o'-lanterns were swiftly turned into suchlike as this stew (never did a good thing go to waste), thick minestrone with other vegetables from our outgoing autumn garden, or pumpkin budino (flan) on Sundays.

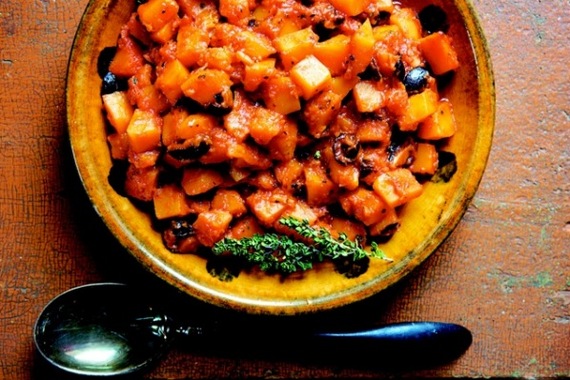

Italian Winter Squash Stew With Tomato, Dry-Cured Olives And Garlic

The combination of fresh pumpkin, cumin- and chili-spiked black dry-cured Moroccan olives, garlic and tomatoes may sound unusual to Americans, but it is superb, at once naturally sweet and intensely aromatic. Pumpkin or squash alone is bland, but the pungent dry-cured olives and garlic carry it to glory. Making this dish a day or two before you plan to serve it gives the flavors time to develop. Avoid serving it with other courses containing tomato sauce.

Serves 6

Ingredients

¼ cup extra virgin olive oil

3 large cloves garlic, sliced

1 cup canned tomato purée, or ½ cup tomato paste mixed with ½ cup water

1 medium-sized butternut or Hubbard squash or 1 small pumpkin (about 1½ pounds), peeled, seeded and cut into 1-inch dice

20 black dry-cured Moroccan olives, pitted and halved

1 teaspoon chopped fresh thyme, or ½ teaspoon dried thyme

½ teaspoon salt

freshly ground black pepper

Directions

1. In a saucepan over medium heat, warm the oil and garlic together until the garlic is fragrant, about 4 minutes. Add the tomato sauce, stir and bring slowly to a simmer, about 4 minutes. Add the squash, olives, thyme and ¾ cup water. Cover partially and simmer over low heat until tender, about 40 minutes.

2. Season with the salt and pepper to taste. Serve immediately or chill and reheat gently before serving.

Ahead-of-time note: This dish can be made up to 3 days in advance.

* * *

Growing your own zucca or selecting pumpkins and squashes

Gardeners with hospitable climates might want to consider planting marina di Chioggia. Johnny's Selected Seeds, which grows and preserves rare heritage seeds, is one of the few sources for it. For other seeds and information on squash and pumpkin varieties, Leslie Land's blog is one of the best resources. Sadly, she died in August, but her vast knowledge and gardening and kitchen advice will remain accessible online. See especially her advice for choosing the best variety of squash and picking a good pumpkin or squash at the market.

Top photo: Italian winter squash stew with tomato, dry-cured olives and garlic. Credit: Hirsheimer & Hamilton, "Italian Home Cooking" by Julia della Croce (Kyle Books)

Zester Daily contributor Julia della Croce is the author of "Veneto: Authentic Recipes from Venice and the Italian Northeast" (Chronicle Books), "Italian Home Cooking: 125 Recipes to Comfort Your Soul" (Kyle Books), and 12 other cookbooks.

Other stories from Zester Daily