Friends make fun of me for having a fireplace going on Netflix. And they're right, it is a bit ridiculous. But we do not deal with real things anyway, only copies. Candles, for example. Longtime chandler Yankee Candle has attempted to copy the smell of just about everything in the natural world, from Fresh Cut Roses to a mixture of Mandarin and Cranberry. Apparently, they can also smell like A Child's Wish and My Serenity. A Child's Wish, you guys.

One wish of children is to become rich. They think that will happen through robbing a bank. Of course, there's no money there. In what some theorists refer to as a postmodern economy, we rarely deal in cash. Cash is already a stand-in, a tangible iteration of what it represents. We know that ancient societies actually traded the goods they valued, operating without the abstraction of cash. And Jean-Jacques Rousseau would assert in his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality that societies began producing surplus, worthless without a cash money system. Cash therefore leads to inequality among individuals as it allows its possessor to obtain hierarchical distinction through the acquisition of unnecessary, "luxury" items.

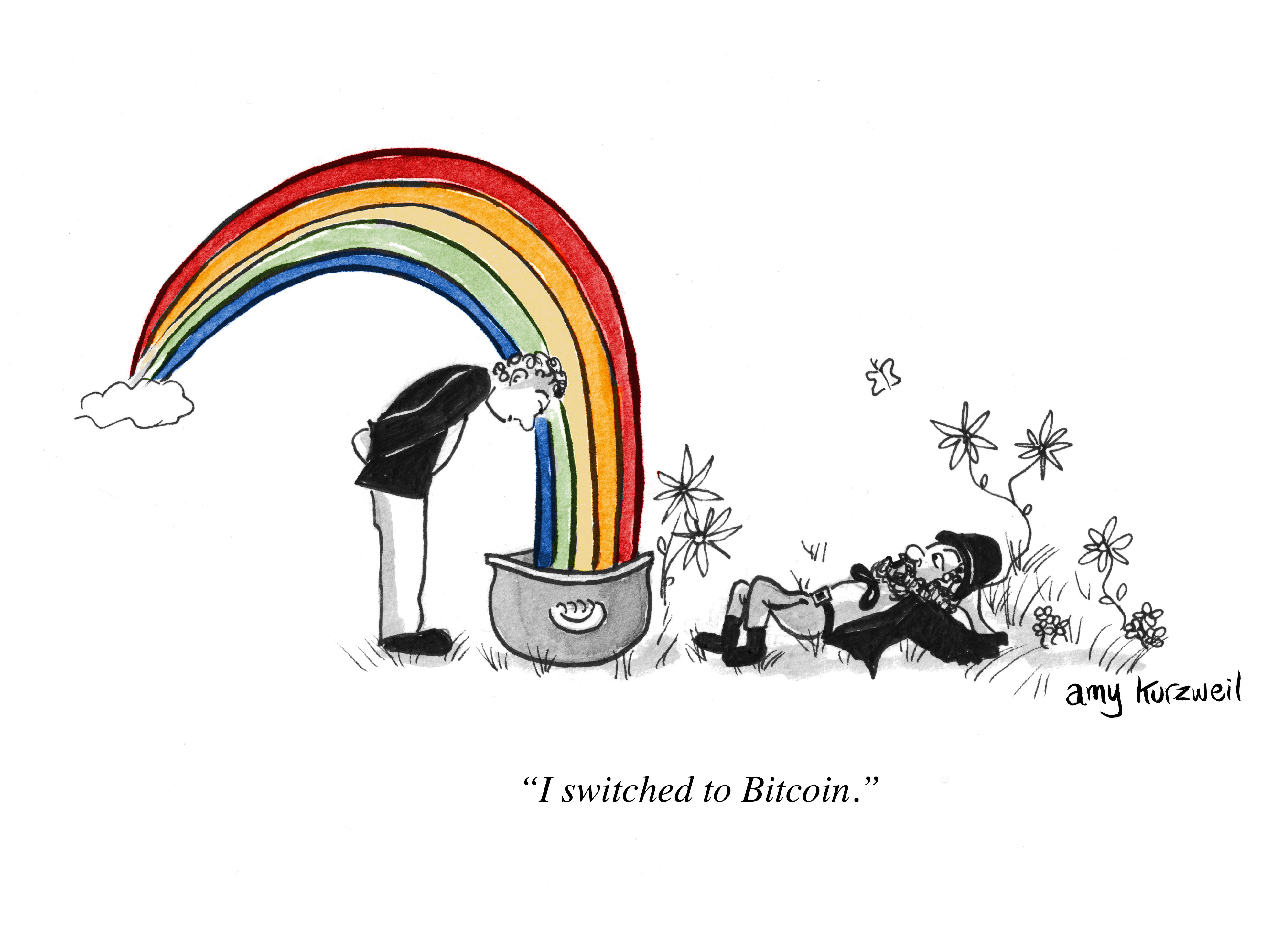

For a historical stretch, cash money was itself valuable, made as it was of precious materials, but it would eventually become but a copy of something valuable. Now we have developed credit, a conceptual stand-in, an intangible copy, for money. Some have even exchanged Bitcoins, digital assets, for real currency. Copies of copies of copies. While the complex function of money centers around production, exchange, and consumption, what matters is not its particular iteration, but how it functions. Its value lies in whether it does what we want it to do.

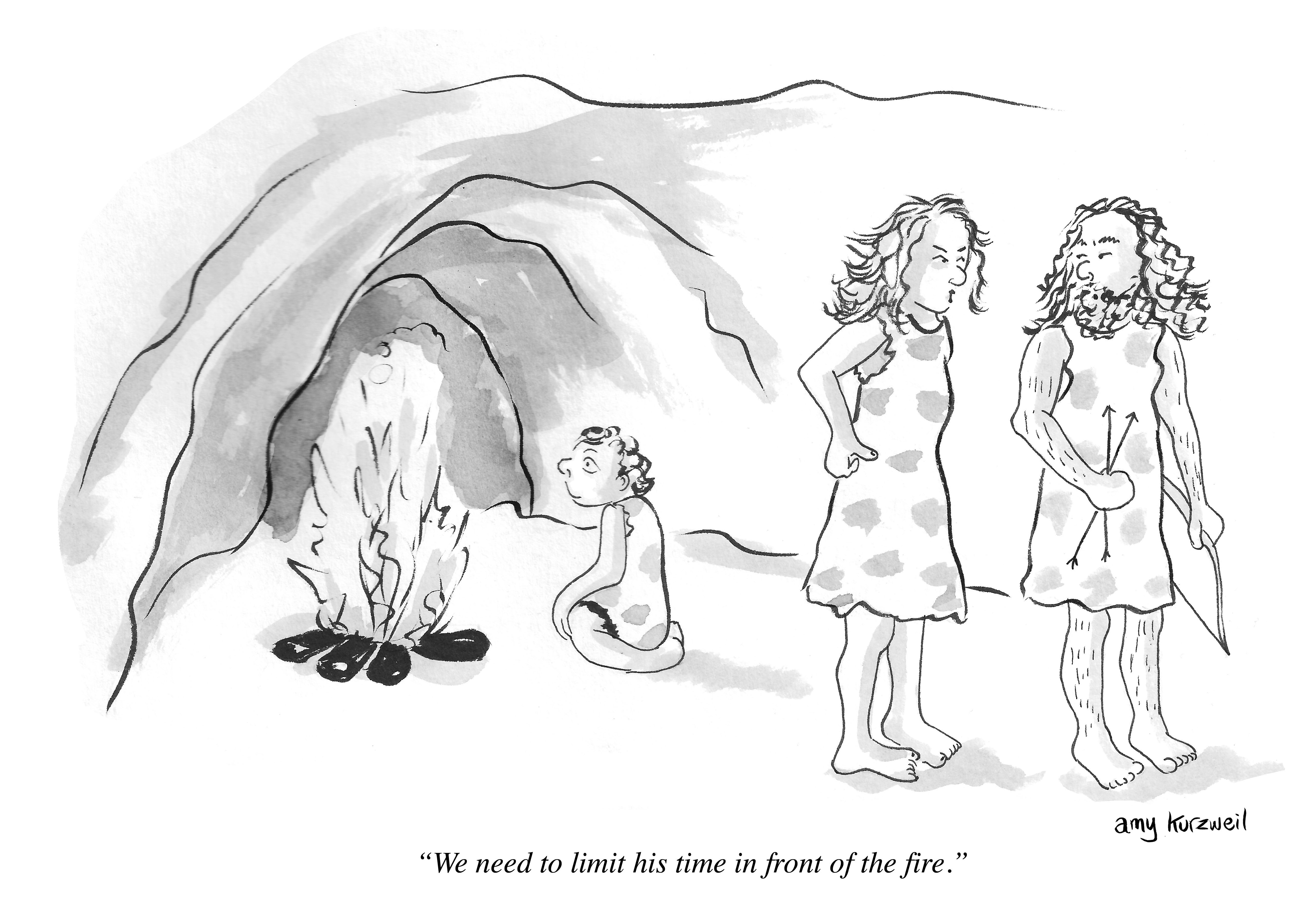

Let us consider copies replicated by AI for functional purposes. Many are fearful, in theory, of the "copies" of AI, and yet they are precisely what we want. What about people going on a vacation? Nearly everyone prefers touch screens to human service representatives, automatic kiosks to human airline personnel. Our desire is for the function to be fulfilled, and this appears to guide our daily actions most. This is not a statement of should, by the way--that is for another article. It does not bother us that pilots are aided by flying instruments, that AI gauges elevation, pressure, velocity. What about the customer service at our hotel? Would we stay at this weird hotel, where a humanoid helps you check in? Do we really care about who checks us into a hotel? Don't speak Japanese? It's okay, they have a dinosaur robot who speaks English, a copy of something, well, awesome.

Also, human being are copies. Though we are each unique snowflakes--or at least American millennials are--we are mostly functional copies of other human beings. Our genetic coding, determined through a mixture of the genes of our ancestors and, of course, chance, results in what individuals are like. Yet, with allowance for accidental qualities, our species copies itself. That it copies itself with a difference each time is responsible for our evolution as a species.

But this is the frontier of this conversation: to what extent the human brain itself can be copied. Recently, philosopher John Searle issued a series of objections to Ray Kurzweil, whose enthusiasm for the future of man and machine is well-documented. Kurzweil has spent his career inventing machines of artificial intelligence and theorizing the merging of human beings with AI. He believes that the human brain can be reverse-engineered. At the heart of their "disagreement" is whether the phenomenon of "consciousness" will likewise be replicated, copied.

But Kurzweil argues that he was never talking about an exact copy, and this is precisely where his observations dovetail with our own. He notes, "Searle writes that I confuse a simulation for a recreation of the real thing. What my book... [How To Create a Human Mind] actually talk[s] about is a third category: functionally equivalent recreation." Indeed, Kurzweil thinks we can create the candle that produces the "fireplace" scent, the television that produces an image of the fire crackling. We can create the functional copy, which is the point. "We already have functionally equivalent replacements of portions of the brain to overcome such disabilities as deafness and Parkinson's disease."

The fountain, stepchild of the waterfall, adorns the public square. The oboe, while not the wind in the trees, produces a lovely sound. The copy is what we have. It is what we were born into. And it will replace us.