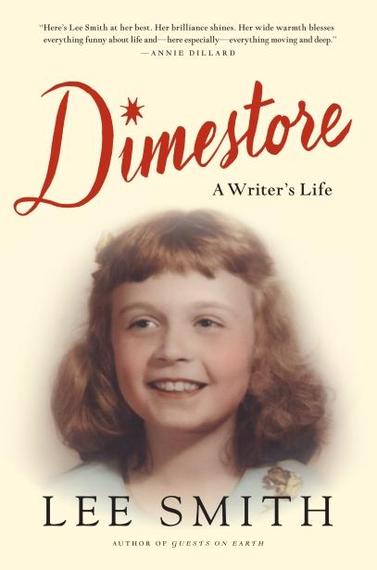

In Dimestore: A Writer's Life, Lee Smith reflects back on her growing up as a daughter of the Appalachian South and as a fiction writer. While she reports that her fiction finally clicked when she wrote about the life she knew growing up, her non-fiction clearly benefits from the same gaze.

You took some moments from your life and used them to spark fiction. In Dimestore, you told about them straight, a non-fiction. What did you learn about writing from these two approaches? What sets apart fiction from non-fiction to you?

Lee Smith: First let me say that I have been writing fiction all my life and publishing it for 47 years. I've never made a real living, but writing has given me a real good life. So why did I decide to turn to memoir now, after all these years? Quite simply, I got a kick start when my Appalachian hometown was demolished by a flood control project. I was present to witness the destruction of my father's Dimestore, which he owned and ran for 55 years. They blew it up along with 60 other main street stores and homes along the Levisa Fork River. Though I'd long known this was coming, I was devastated! A few years later, as the project continued, my parents' home (the house they built and lived in for 65 years, the only home they ever had) was bulldozed too. This time, I couldn't even be there. I couldn't stand it.. Several local people rescued the front door knocker -- brass, with a big engraved "S" for Smith on it -- and sent it to me here at my home in North Carolina in a handmade box frame. I opened the package and burst into tears and cried for two days. Then I sat down and started writing this nonfiction book, making verbal pictures of all those places that are gone now, and all those dear familiar faces, those people who lived and loved and worked and had their being in that town. I couldn't quit. I just kept writing.

The difference between using the stuff of your life for fiction and nonfiction is enormous. I find it much easier to tell the truth as I see it in fiction than non-fiction; in fiction, you can rearrange events and facts to prove your point or emphasize your theme or simply make a coherent narrative. Real life is messy -- in fiction, we can create an order, a shape, out of the chaos of our lives. Another problem with nonfiction is that what we believe to be true may not be true at all -- it may be just our own opinion. Often in Dimestore, I found myself writing a a sentence and then saying, "Is this true? Is it?" Who knows? On the other hand, the great -- and most surprising, to me -- gift of writing nonfiction is, quite simply, MEMORY -- and at my age, this is major! The more you write, the more you remember. This is the most precious gift of all.

I found myself agreeing with the lines: "For a writer cannot pick her material any more than she can pick her parents; her material is given to her by circumstances of her birth, by how she first hears language." But then I stopped and played devil's advocate -- is there any exception to this rule? What does it mean for you in practice? How does it impact a writer's ability to write about things or ideas influenced by their later years?

Lee Smith: Of course there are many, many exceptions to this rule. I'm afraid I was extrapolating from my own experience in that statement. Place has always been paramount for me as a writer simply because I was born into such an extraordinary place which determined its extraordinary culture -- a small coal mining town set deep in the rugged mountains of far southwest Virginia, very near eastern Kentucky, and very remote and isolated in those days. My father owned and ran the Ben Franklin Dimestore on main street; my mother was a home economics teacher at the high school. I was an only child born to them late in life, so I grew up mostly around the older folks in my daddy's big, raucous family. I don't know how many nights I fell asleep on somebody's lap on somebody's porch trying to stay awake long enough to listen to the end of the story being told. Even today, stories come to me in a human voice. All I have to do is write them down. Sometimes it is the voice of the narrator or another character in the story, but often it is the voice of the story itself. I'm really a storyteller instead of a writerly writer.

And since it's true that in a long life of writing, we all DO sooner or later use up our own given material, our childhoods in our families of origin...what then? Again and again, I have turned back to the human voice, using the techniques of oral history, interviewing real people in order to flesh out the lives of my characters, often people totally unlike myself. People love to tell their stories. The world is filled with variety and wonder -- all there waiting for us to ask, things we could never imagine... You just can't make this stuff up! Anne Tyler once said, "I write because I want to have more than one life." Me too.

One of my students recently asked me how to handle objectives family might have to being featured in a memoir. You write about women struggling for "permission to write." What advice would you have for a writer afraid of hurting feelings or facing criticism of their desire to share their personal stories?

Lee Smith: In writing, as in the rest of life, we are always responsible for any pain our actions may cause others But I think each would-be writer has to make this decision personally, on a case-by-case basis. We should never write simply for vengeance, to settle scores, or to purposefully cause pain to living people. However, in writing to set the record straight, or to present our own point of view, or to change something, we may unwittingly step on somebody's toes. This is the risk we take. But it's worth it. Remember this: it's YOUR LIFE. It's your story. You have a right to do this. Your life is precious -- it's important. This is the only life you've got. Records are precious. So go for it!

I love the image that ends the chapter, Blue Heaven, of the four girls walking and laughing and the one that has "no idea what's going to happen to her in the years to come." Would you have wanted to know what was going to come for you as a woman, mother or writer before it happened? Why or why not?

Lee Smith: No, I would not have wanted to know what was going to happen to me as a woman, mother, or writer before it happened, because then I would not have lived so hard, experienced it so deeply, felt so much, even if it's painful, I want it all. Just like the girl at the end of that chapter!