Imagine a world in which a woman keeps bees in secret. She is not supposed to leave her house without permission, she is not supposed to work, and she is certainly not supposed to work as a beekeeper, a job reserved for men. But she does. And when she watches her bees take flight, she dreams of her own freedom and freedom for all Afghan women.

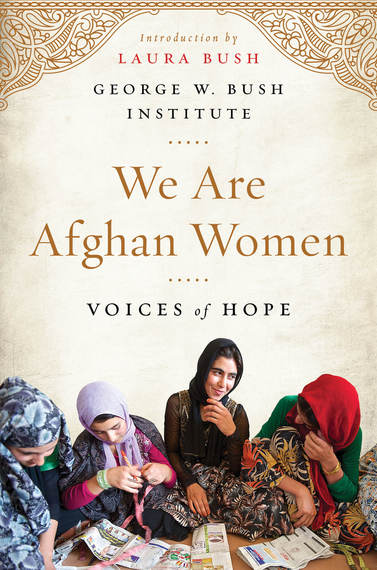

The stories told by the women in "We Are Afghan Women: Voices of Hope" lift the veil on Afghan life, before the Taliban and after, and also further back, to the time before the Soviet invasion and then its aftermath. They speak of the price of decades of war, of their struggles to survive and find a place in the world, and how, despite everything, they have found their worth as women.

Zainularab Miri, known as "the beekeeper," tells of her own brave story to work in Afghanistan in "We Are Afghan Women." We are honored to share part of her story here.

"I was born in Kabul, into a very modern, open-minded family. My father was a member of a council of elders, the council of wise men from his village, but he wanted all of his children to accumulate wisdom, daughters as well as sons. He and my mother gave me all the same chances that my brothers had. Everything my brothers did, I did too. If they ran around playing soccer, I ran around playing soccer. If they learned to play chess, I learned to play chess. I was never a stereotypical Afghan girl, playing only with dolls or sent off to wash clothes. Most importantly, I went to school. I attended a well-regarded elementary school. In high school, I concentrated on studying Dari, my native language, and even some English.

"Although my family was very progressive, Afghanistan is a very traditional society. Historically, men have frowned on women working outside of the home. It has been considered an affront to the man that he cannot support his wife himself or be a father who cannot support his daughters. But I wanted a profession, and for a woman, one of the best ones was teaching, so in college I studied education and child development."

Zainularab taught Dari to eleventh and twelfth graders, but after she married and had a child of her own, she taught Dari to first graders in a school closer to her home. As the Taliban took control of Kabul, Zainularab's family moved to the Ghazni province, in the eastern part of Afghanistan. There, she and six other women taught girls in secret, risking their lives. But she did not just teach.

"I was very lucky to have married a man who is just as open-minded as my father. As I moved around teaching, I realized that there were five men in our area of Ghazni who kept bees. In Afghanistan, beekeeping is traditionally a male job. But that only made me more passionate to learn the business. As when I played soccer or chess as a girl, just like my brothers, I wanted to be like these men. I wanted to keep bees. I started buying two hives from a friend of my family's, and as part of the bargain, I asked him to teach me what he knew. I, the teacher of Dari, became a student of bees.

"Once I had my two hives, I wanted to expand. I was paid as much money for my nectar and honey as the male beekeepers were. No one thought to segregate my honey or pay me less because I was a woman. And each year, I added more hives and more bees. The Taliban did not know. They did not know that I was working, and that every year I was determined to double my cases of bees.

"For a beekeeper, even a woman beekeeper, the part that's the most challenging is making the queen bee. Without a good queen, the hive cannot be productive. The queen is what gives life to the hive, laying as many as 1,500 eggs in a peak day. In a colony, the queen is the one bee that will never leave the hive. She spends her entire life inside the honeycombs. She can never escape the walls around her, never take flight. My honeybees could spread their wings and move from flower to flower or plant to plant, drinking in the sweetness. They could come and go as they pleased. I wonder if that is part of what makes honey so sweet, if it is the taste of that feeling of freedom, of flight.

"As women in Afghanistan, during those Taliban years, many of us felt like the queen bee, trapped in our own hive. The bees build their honeycombs in the darkness. We too survived by working in darkness, behind curtains, under the cover of cloth; even my beekeeper suit hid who I was. But the darkness was appropriate, because the Taliban period was a very dark time for women.

"When the Taliban fell however, we found that we had our own honey. The girls who had been in seventh or eighth grade when the Taliban took hold were now in twelfth grade. Those years had not become a void in their young lives. They had continued with their education. Like the bees, they couldn't leave the hive, but when it was over, their learning was our honey, the residue of all their hard work.

"Each season watching my bees leave and fly off and then return laden with sweet nectar for honey fired in me a passion to be able to move about freely. But not just for me, for as many women as I could find. I believe that in order to change a country, first you must work on the women."

Watch an animated video of the beekeeper's story, and read more about her life and 28 other inspiring stories of resiliency in the book, "We Are Afghan Women: Voices of Hope."