Daft Punk at O2 Wireless Festival, July 16, 2007, by Fabio Venni via WikiMedia Commons

As the old saying goes, better late than never. That could apply to the arrival of electronic dance music or EDM to the mainstream. Compared to rock and hip hop, it took more than 30 years for this once-underground sound to finally reach its current commercial peak, thanks to such stars as Daft Punk, Skrillex and Avicii. The popular music of choice these days for millennials, EDM is reportedly a $4 billion annual business that attracts audiences to events like Ultra Music Festival and Electric Zoo. (Last year, about 400,000 people flocked to the Electric Daisy Carnival (EDC) festival in Las Vegas).

Now the history of EDM in the U.S. is told in a new book The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America by Michaelangelo Matos, who has extensively covered electronic music for Rolling Stone, NPR and Red Bull Academy. In this interview, Matos talks about the evolution of the music from its early roots to its present popularity.

Why is electronic dance music so popular now compared to the '90s when there was a crop of dance music artists such as Moby, Fatboy Slim, and the Prodigy?

The Internet. It's a fallacy to compare somebody like Skrillex to Kurt Cobain because a lot of people did, but it's also true. They're nothing alike artistically; they're a lot alike socially and they're very alike historically. It's the Sex Pistols effect. When did the Sex Pistols go gold? Fourteen years after the album [Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols (1977)] was released. Why did they go gold? Because they never stopped selling records. They stayed put. People grew up thinking this was always the most popular music around, when nothing in fact could be further from the truth. And that's dance music -- specifically, that's Daft Punk. I have that quote in the book from Gerry Gerrard, their old booking agent: "They sold 3,000 copies a week, every week. It was just consistent, forever." That's what happened with dance music as a whole. It never went away. It was easier to assimilate that as a kind of pop music when you can just access it. You couldn't do that in the '90s.

Dance music also faced a lot of "Disco Sucks" rockist crap. There was a lot of resistance. And it wasn't like there was a shortage of good music outside of dance music in the first half of the '90s. If you just wanted to listen to rock in the early '90s, there was nothing wrong with that. There were loads of good rock to go around. If all you wanted to do throughout the '90s was listen to hip hop, go nuts. For Americans, there was no reason to switch. So they didn't.

The origins of the genre can be traced back to the early '80s in the Midwest with Chicago house music pioneered by the late DJ Frankie Knuckles along with the development of Detroit techno. Why did electronic dance music flourish in that particular region?

You have to make your own fun. Particularly in Chicago, this was the offshoot of disco. Frankie Knuckles came out of disco -- he was a New Yorker, and he brought to the Midwest that style of making your own edits and mixing. Before Frankie, disco was about playing records for people. It wasn't necessarily about mixing. He promulgated that.

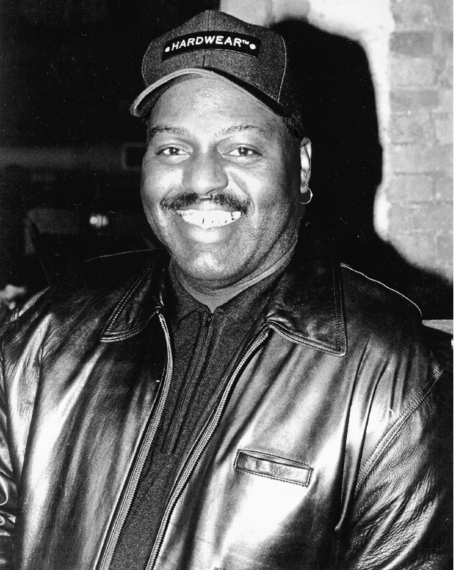

Frankie Knuckles, circa 1988, by Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images. Image provided by Dey Street Books

Also, "disco" was a bad word. The Warehouse [where Frankie deejayed) was a gay black club for most mostly under-25s and teenagers; it was completely underground. It had a small core audience and that core group got bigger. But there was nothing like the Warehouse in Chicago prior to the Warehouse. And that's Robert Williams, the guy who opened it, as much as Frankie. He came to Chicago from New York and wanted to make his own Loft, and it set off a chain reaction. Other DJs started playing in Frankie's style. Farley "Jackmaster" Funk took his entire playlist from Frankie. They all did.

New York DJ Frankie Bones is credited for bringing rave culture to the States after his trip to U.K. in 1989 by introducing events known as Storm Raves.

He was one of the first people along with Todd Terry to make tracks that fused hip-hop and early house music. He was making DJ tracks with samples and drum machines and using the obvious hip-hop source material. He saw what happened in England -- he was like, "I have to do this now." You get a real sense that every party was a progression from the last party. The Storm Raves were just pure mayhem. People would slam dance and it was so different for anywhere else. The music is getting louder and more obnoxious. You can map the progression of the scene through those parties all through '92. And the Storm Raves were the bellwether in many ways.

The evolution of electronic dance music in the '90s coincided with the emergence of the Internet, in which fans talked the parties and the scene in general through the message boards.

And also to talk about drugs. No one thought anyone was going to read this stuff except each other. It took until the mid '90s for those lists to go up to 500 people. There weren't that many members because there weren't that many people online at all. It's a way to talk about the scene because there's no one else was doing it. This was a very small secretive self-selecting society, and that's what the internet was at first, too.

There is no escaping the fact that drugs -- especially Ecstasy -- drove the movement, especially the rave scene.

Obviously so. Whether the people who invented the music liked it or not -- the techno people of Detroit who disdained drugs -- that's what it became. It's very significant and it certainly fueled the music. Certain tonalities, certain sounds, and certain patterns and certain production styles lent themselves to being heard on giant systems in altered states.

With the drug factor in mind, there has always been an uneasy relationship between movement and law enforcement authorities, most notably with police raids on rave parties in Milwaukee in 1992, and in Utah in 2005.

[The Utah party raid] was like the nail in the coffin as far as a lot of people were concerned. 2005 felt like the nadir of the scene. I remember watching it [on YouTube] and be like, "Oh my God, this is horrible," and everybody started to hear the horror stories. "Grave" [the party in Milwaukee in 1992 that was raided] happened when I was a senior in high school. You heard rumors and you saw it on the news and you were like, "What? There are mass arrests at these things?" It was enticing. I talked to more than one person who was like, "I heard about "Grave"! I'm gonna go to the next one!" It made people want to do it. And [there's] these other things where it's like, "The cops are coming in and cracking skulls." It makes you not want to do it.

Yet those incidents hardly prevented people from mounting and going to these EDM parties.

They stopped calling them "raves" -- they started calling them festivals. I spoke to a friend of my sister's, who is a party habitue -- she basically started going to EDC in 2012. She was like, "These aren't raves. Raves are for losers." I would encounter that sort of thing a lot talking to younger people, and they were like, "They aren't raves because raves are old. That's not what we do." That's exactly what you do, except it's supervised.

Electric Daisy Carnival 2010 in Los Angeles. By Npatchett via Wikimedia Commons

So what event made the music industry finally take notice that EDM was a viable commercial entity?

It was Daft Punk at Coachella [in 2006]. That's it. Daft Punk at Coachella for dance music is the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. They owned the [show], no one else came close. It was the presentation, it was the music, too. They're Daft Punk. Daft Punk's genius was to just utilize the tricks of dance music as themselves but make them seem like pop songs. They were amazing at that.

With the current success of EDM how do you see its future? Has it finally staked its claim alongside the genres of rock, pop and hip-hop?

It's too big to be ignored. The numbers of people may well shrink but they won't disappear overnight, and they're the same numbers the more established genres have, or bigger. Every generalist rock festival is at pains to include some EDM, because they need the numbers. It's not really possible for more pop artists to borrow the sound because it's been saturating pop for nearly a decade.

Michaelangelo Matos' book 'The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America,' published by Dey Street Books, will be available on April 28. For information, visit the book's Tumblr site.