Internal strife, poor economic performance, major importation of food supplies, and severe crowding along a thin strip of arable Nile land can only mean disaster for Egypt in the coming years.

"The danger of not developing new land is expansion over fertile land, such as around Cairo in 20 years," said world renowned expert Farouk El-Baz, setting off the alarm he's been sounding for a couple of decades.

The current Nile Valley and its Delta are too squeezed to handle Egypt's exploding population - estimates of 85 million -- and rising needs.

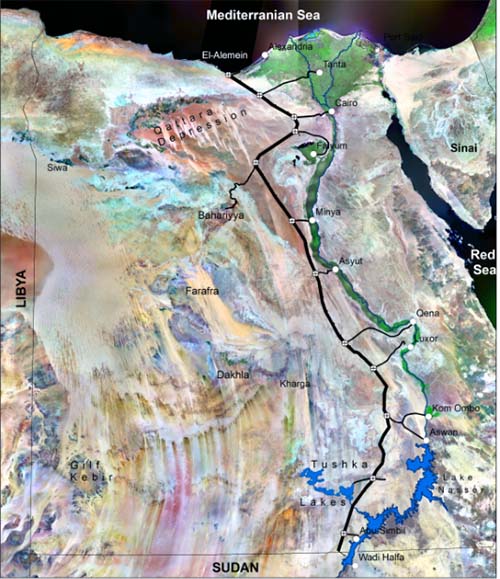

But it doesn't have to be that way if high-density urban areas and people move west, incrementally, literally into the desert, along a parallel corridor from the Mediterranean Sea to Egypt's southern border with Sudan, he argued.

Farouk El-Baz' parallel urban corridor for Egypt (courtesy Jason Margolis)

Farouk El-Baz' parallel urban corridor for Egypt (courtesy Jason Margolis)

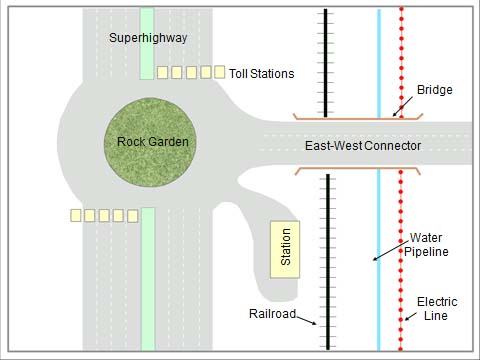

All it takes is extending living spaces into the desert, creating a north-south superhighway connected to the main urban centers from east to west, building a fast rail system, providing a water pipeline, and powering it all with the sun and wind, amply available, in that geographic area.

It's a daunting project with a humongous price tag.

East-West corridor and superhighway (courtesy El-Baz)

East-West corridor and superhighway (courtesy El-Baz)

El-Baz believes the return on the investment for future generations far surpasses the projected cost.

He figures it's probably four times what experts originally estimated at six billion dollars some 20 years ago when he presented his plan to Egyptian officials.

The proposal would provide countless opportunities for the development of new communities, agriculture, industry, trade and tourism around a 2,000-kilometer (1,242 mile) strip of the Western Desert.

Water is a critical resource in the Arab world but El-Baz has it all figured out: the corridor would take advantage of the gently downward-sloping plateau west of the Nile from Aswan to the Mediterranean and create a new path for agriculture.

"Water for human consumption along the north-south corridor would be supplied from Lake Nasser, Egypt's immense southern reservoir (behind the Aswan High Dam)," he explained. "Crop production would be limited to areas where there is groundwater within the Nile Valley and west of the Delta."

El-Baz envisions the corridor to be built in stages, to attract poor Egyptians from the clogged cities to the open land. The first step would be expanding large cities westward along the Nile, one mile at a time.

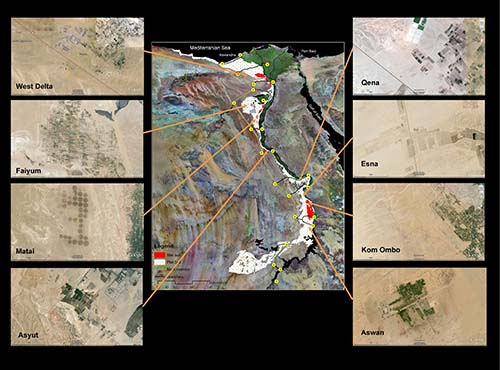

The Aswan/Kom Ombo area to the corridor, for example, would be ideal for wheat production and save Egypt the staggering expense and trouble of having to import this vital commodity. It is a plain of about 1,000,000 acres of good flat soil.

The proposed corridor would pass west of 10 million acres of flat land with a zone of it capitalizing on the Nile's rich silt. Several areas within that projected zone are already in use by local people to produce agricultural crops.

A private/public partnership would be tasked with building the superhighway and a modern rail network to connect the urban areas, north to south, to ensure these two projects don't fall victim to typical government bureaucracy and sloth.

Egyptian development corridor (courtesy El-Baz)

Egyptian development corridor (courtesy El-Baz)

I asked El-Baz if there was enough water in Lake Nasser to sustain mass migration and development given rights disputes Egypt has had with Ethiopia and Sudan over the Nile's waters.

"The people who would live around the corridor are the same that live in the valley today - the water needs are the same," he said. "As they move west a mile at a time, they take the needed water though pipelines like any development today."

Water for agriculture would come only from where groundwater exists beneath the new tracts of land. There are currently eight tracts within the zone west of the Nile.

Eight tracts west of the Nile using groundwater (courtesy El-Baz)

Eight tracts west of the Nile using groundwater (courtesy El-Baz)

The groundwater originates from seepage within the Nile so it is the same amount of water for use in Egypt and has nothing to do with Sudan or Ethiopia, he explained.

In 1978 El-Baz told me there could be water under the Western Desert. Today he said there's an ample supply in the area of the desert's five oases.

Few Egyptians bought into moving all the way into that wilderness when he worked with the late president Anwar Sadat to encourage creating new urban areas, hence his new call for such a move to be gradual.

The benefits, according to El-Baz, are:•Ending urban encroachment on agricultural land in the Nile Valley•Opening new land for desert reclamation and the production of food•Establishing new areas for urban and industrial growth near large cities•Creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs for Egyptian labor•Arresting environmental deterioration throughout the Nile Valley•Relieving the existing road network from heavy and dangerous transport•Initiating new ventures in tourism and eco-tourism in the Western Desert•Connecting the Tushka region and its projects with the rest of the country•Creating a physical environment for economic projects by the private sector•Involving the population at large in the development of the country•Giving people, particularly the young, some hope for a better future•Focusing people's energy on productive and everlasting things to do.

Once the proverbial dust settles on the unrest in Egypt, he hopes officials will take serious steps to implement his proposal in a bid to ease the country's economic, social and environmental problems.

The Egyptian-born El-Baz is Director of the Center for Remote Sensing at Boston University, and is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Science at Ain Shams University in Egypt.

He began studying the Earth as a geologist, before turning to outer space as supervisor of lunar science planning and operations at Bellcomm, Inc., a division of AT&T, that conducted systems analysis for NASA. At NASA he helped select Apollo 11's landing craft touchdown location.