Eve Ensler has inspired women worldwide to love their vaginas and their whole selves, so you'd think the award-winning playwright of The Vagina Monologues was one of those rare women who's felt comfortable in her skin. You'd think wrong. Until recently, the award-winning playwright has felt so excruciatingly uncomfortable, she effectively disembodied herself.

It's no small irony that the tireless activist has moved women of all ages to love and protect their bodies but, for much of her life, she has neglected and abused her own. Given her mother's remoteness and father's sexual abuse, the extreme measures Ensler has taken to dissociate from her body -- promiscuous sex, anorexia, substance abuse -- start to make sense.

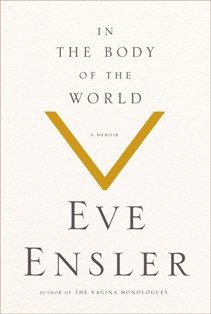

If a lethal cancer hadn't forced Ensler to take care of her 57-year-old body, she may have gone to her grave never knowing what it's like to feel embodied. Happily, she has lived to tell about her early separation and eventual union with her body, herself and the world in her new book,

In The Body of the World. The memoir completes an unintentional body-image trilogy, which also includes The Vagina Monologues and The Good Body.

I was lucky enough to catch Ensler on day one of her 13-city book tour. What follows are questions and answers from our recent phone interview. Be forewarned: Ensler's message may hit uncomfortably close to home. Although it hit a little too close for my comfort, it's exactly what I needed to hear. Read on and see what you think.

Q. How did you preoccupation with women's bodies start?

A. It began with my own body. A series of circumstances forced me out [of my body] early on. In an attempt to get back, I began asking other women: "Do you live in your body?" "How did you get in?" That exploration made me aware of how many other women didn't live in their bodies. Often if you go deeply enough into your own story, you find the story of other people.

Q. The author of The Vagina Monologues getting uterine cancer sounds like a cruel joke, but it's been a real gift. How so?

A. There's nothing good to say about the disease itself. It's arduous, terrifying, horrible. But I will say, because I had incredibly loving people around me, I was able to clean out a lot of my own personal pain. That was a gift! And because of cancer, I'm in my body. From being pricked and poked to being ported and chemo-ed, there's no way you can not be in your body.

Q. Cancer survivors often talk about feeling disconnected from their bodies, but you established a deeper connection. How's that?

A. Before cancer, I was obviously disconnected. I had a tumor the size of a mango inside me and didn't do anything about it. It wasn't like I didn't know something was wrong. But cancer blew off that somnolence, where you're half awake and half asleep. When I woke up from surgery and had tubes and ports coming out of me, I was just a body. When you come into your body, you become porous. There is no separation between you and the world.

Q. You lost 30 pounds with cancer treatment, but you didn't become anorexic. You write about risking your life for a hamburger! But you did struggle with anorexia earlier in life. Tell me about that.

A. Anorexia was a period where I didn't want to be in my body, but I wanted control over it. It seemed like the only thing I could control. I don't know how it ended, but I finally got to this place where I had enough love around me to "get" that I actually wasn't in control. And I began to direct my need for control into writing, and left my body alone.

Q. How would you describe your body image before cancer and now?

A. When I wrote The Good Body, I turned 40 and suddenly had this stomach. It seemed like the end of the world. Because I didn't value my body. I was constantly judging it, but I also didn't live in it. Now I begin most days rubbing my scar, thinking, "How incredible that I got to live." I have such respect for my body. I can't believe it's been so clever to figure out how to survive without seven organs and 70 nodes. Even if I start to go, "You look a little old and saggy," it doesn't last because I know I could have easily died. Whatever happens, if I wake up tomorrow and the cancer's back, I'm grateful because I will die in my body. That means I will die connected to the earth and other people.

Q. Why do you think so many women struggle with bad body image?

A. We can go down the list: capitalist ideology, image making, hatred of girls and our bodies, the desire of the world's patriarchal mechanisms to control women's bodies. It's kind of a genius thing. They got women to be preoccupied with their little country called their body while they got to take over the world. One of the most radical things women can do is to love their body. The truth of the matter is, every moment we spend worrying about our bodies, and not necessarily taking care of them, somebody is figuring out how to take money away from the poor, destroy the environment, drill, frack, burn, rape and violate women, and we're not paying attention. Be radical: Love your body!

Q. Anything else you'd like to say?

A. What we're told creates our experience. If someone had told me before chemo, "This is going to be utterly devastating. You just have to survive it," that would have been my experience. But somebody said, "You have the opportunity to burn away your past and your demons. The chemo is not for you, it's for your perpetrators, your cancer." I would love to see chemo wards become transformational zones, where they'll work with us on how to use cancer to transform ourselves.

Eve Ensler photo by Brigitte Lacombe

If you're struggling with an eating disorder, call the National Eating Disorder Association hotline at 1-800-931-2237.

Jean Fain is a Harvard Medical School-affiliated psychotherapist specializing in eating issues, and the author of "The Self-Compassion Diet."

For more information about Jean Fain, click here.

For more by Jean Fain, L.I.C.S.W., M.S.W., click here.