La sangre llama. Blood calls. Every Latino child in the United States, even those who can't or won't speak Spanish, has heard that proverb. Its English equivalent, Blood is thicker than water, seems tame, even sluggish. A measure of thickness isn't the same as a call to action. As a retired professor of English literature, I can look back on a lifetime of trying to respond to that call. Although Spanish was my first language, an intense awareness of my Latino ancestry began during my twenties, with a brother-in-law's wedding toast: "To the Anglo-Saxon attitudes that bind us together." Although I was surrounded by those attitudes, and even would spend a career teaching their literature, they were not mine. I was the daughter of an undocumented Spanish immigrant whose story below sums up my attitudes.

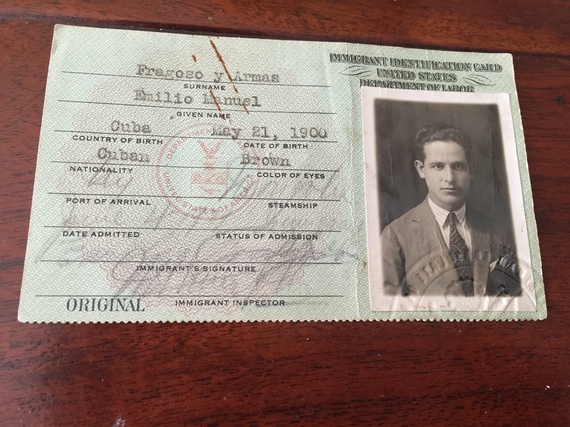

On June 4th, 1929, my father sailed into New York City on the steamship Margolis. He arrived clutching a fake green card issued five days earlier by the American Consulate in Havana. Now over eighty years old, this Immigrant Identification Card sits framed on my desk. Issued by the Department of Labor as VISA No. 3248, it includes a photo of my father in a grey linen jacket and herringbone striped tie, his eyes focused on a future that would include two daughters born in the USA and five granddaughters he would never meet. All seven women are college graduates.

Born in 1902 in one of the westerly Canary Islands--La Gomera, where Columbus replenished his ships on all four voyages to the New World--my father was a Spaniard by nationality. The green card, however, claims his country of birth to be Cuba, and his birthdate, two years earlier. All that data belonged to someone else. My father borrowed a birth certificate from a Cuban-born cousin and presented it to the American Consul in Havana as his own. After disembarking into the violent world of the 1929 Depression under the cousin's "given name," my father carried this man's identity into a brave new world of breadlines and desperate jobless men.

Why was it necessary to secure a sham document from the American consul in Cuba? Family legend had it that Spaniards could not enter the USA easily because of the 1898 Spanish-American War, a memory still active a generation later thanks to Americans who did not forget to "Remember the Maine!" Less legendary, however, was the Immigration Act of 1924, which passed with overwhelming congressional support and targeted immigrants based on their nations of origin. Also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, its declared aim "to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity." Along with other Southern Europeans and all Jews, Spaniards were regarded as "undesirable"--as hungry and sickly and less able to adapt to North American culture. Those trying to enter the USA after 1924 encountered such restrictive immigration quotas that it was less risky for my father to pretend to be a Cuban national. The Act set no limits, amazingly, on immigrants from Latin American countries.

This was not my father's first immigrant experience, although it was his first in a new language. He had sailed from the Canary Islands to Cuba ten years earlier with his family, aiming to find work in the copper mines. Instead, he signed on as an apprentice to a family of Turks, itinerant tailors who sold copies of Cairo-Western fashions to farmers and miners up and down the dirt roads of eastern Cuba. He served as their bookkeeper, entering credits and debits and customer measurements into a lined notebook in his elegant calligraphy. He worked with these Turks for nine years, always giving a part of his wages to his family, now settlers in Matanzas living hand-to-mouth under the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, known to Cubans as "Nero the Second"--un segundo Nero. Although assured a steady income with these kindly employers, my father wanted más mundo than tailoring across the Cuban provinces. He decided to leave for el Norte. By now twenty-seven years old--thin, grim, and still unmarried--he readied himself for yet another New World. His Turkish employers gave him their blessing and a green gabardine money belt. It would carry years of savings from his wages as their employee.

In May of 1929, my father embraced his parents for the last time and headed for the steamship in Havana harbor. Within a week he was greeted by that "Mother of Exiles" in New York City, the Statue of Liberty: Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.... My father would not, could not, read these English lines until years later, when he had a wife and children, a profitable bodega, and the deep vein thrombosis that would kill him in his fifties.

But on that June day of 1929, dragging his cardboard suitcase across the pavements of New York City, his focus was on survival. After checking into a small furnished bedroom in a cold-water flat off Broadway and 134th Street--a room whose window looked into a sunless courtyard--he sewed his savings into the mattress. The next day he went looking for work.