Why do writers embrace a particular genre? Is it a conscious process? "I love writing. Should I write fiction, non-fiction, plays?" Or do writers simply fall into a genre driven by inspirational experiences? "I read Moby Dick as a teenager and then knew what I wanted to do in life."

For the last three years I've moderated a panel at the annual Hunter College Writers' Symposium titled Literary Road Show: Pitch the Experts. Writers attending my panel are invited to give a brief "elevator pitch" of their book proposals to the panel, which includes leading editors, literary agents, and other publishing-world experts. The variety of genre pitches begs the question of why that genre. Then, to my delight, when I listened in at the afternoon fiction panel at the conference, the moderator's opening question to the panel of award-winning novelists was "Why did you choose to write novels rather than other genres?" The variety of answers led me to conclude that there is no useful answer to the genre question: writers just write. Thus, I put the question to rest--or thought so.

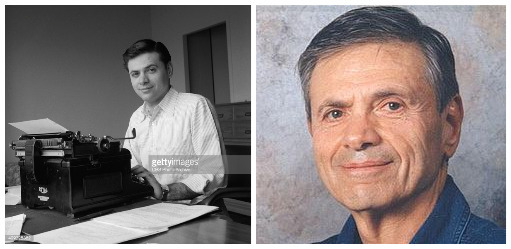

But it hauntingly returned when I learned that playwright Ronald Ribman, whose eminently successful career I've followed for over thirty years, switched genres.

Ribman is a critically acclaimed dramatist. Theater critic Martin Gottfried called one of Ribman's early plays, Harry, Noon and Night, "unquestionably the most exciting, the most original, the most theatrical thing that has appeared this season.... It is wildly unique, written with a maniacal ferocity and it comes from a mind that is bursting with stage-oriented energy."

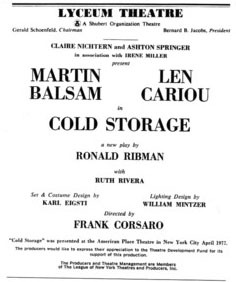

Since then, Ribman has won a slew of awards for his plays, which have appeared both on and off-Broadway, including the Obie award-winning Journey of the Fifth Horse, starring Dustin Hoffman; Buck, starring Morgan Freeman; and Cold Storage, starring Martin Balsam and Len Cariou, which received the Dramatist's Guild's prestigious Hull-Warriner Award and was subsequently nominated for a Pulitzer prize.

His television and film credits include: the CBS Playhouse special, The Final War of Olly Winter, which received five Emmy nominations; the screen adaptation of Saul Bellow's novel Seize the Day, starring Robin Williams and Jerry Stiller; and for United Artists, Bernard Malamud's The Angel Levine. The New York Times has acknowledged that, "Mr. Ribman has long been one of our most independent-minded, moral, and daring playwrights." The Times also praised his television play The Final War of Olly Winter as "the most moving original television play of the season...a brilliant introduction of the CBS Playhouse...that advanced the artistic horizons of television drama." Ribman has been honored by the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, The National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim foundation, and Rockefeller Foundation for his "sustained contribution to American Theater."

That's an impressive portfolio of success.

And now, after seven years of writing, Ribman has just published a novel, Infinite Absence, which he says "may well be the single most important work of my career." And it's not just a novel. It's an epic quartet published all at once!

I interviewed Ronald Ribman to learn about this new work and to explore the new direction he has taken with his writing.

Starr. Why on earth would a successful playwright suddenly shift gears and elect to spend seven years writing in a totally different genre? You did tell me it took you seven years?

Ribman. Yes. And then some. But I didn't exactly "elect" to write a novel. It kind of elected me.

Q. How's that?

A. I was doing something--what it was I don't remember anymore--when a line suddenly presented itself to me. Just sort of walked up, said hello, and popped itself into my mind. I couldn't shake it. The following day, because it still hadn't buzzed off, I went over to the computer and typed it in. And that was the beginning of Infinite Absence. And for the next seven years, six days a week, for about six hours a day, that's pretty much all I did with that computer--taking hold of a line with all its ambiguities and following it along.

Q. Is this your usual work method? Is this the way you write your plays?

A. I don't really have any usual work methods. And if I thought I had discovered one I could use over and over again, I can't imagine anything much good could come out of it. It would be a cardboard land, in which cardboard figures thrashed about in their pre-arranged modular boxes, their fate totally controlled, totally pre-destined. The human mind is far too indeterminate to be confined this way, too filled with random, unplanned-for thoughts that pop like bubbles into and out of existence. Just sometimes, at a moment seemingly no different than any other moment, and for no particular reason you can conceive of, one of them jells itself sufficiently to let you engage it further, gives you a jumping- off place toward a destination you're not even sure is there.

Call it a voyage into a bubble-land. But if you enter this place, which surely has chosen you more than you it, and you let the characters that dwell there respond to each other without too much conscious manipulation, you may actually discover something worth writing about. And this is your first draft. The moment when, if you return to your beginning, to quote T.S. Eliot in probably one of the most profound statements ever made concerning the arts, you will find "the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time."

Thereafter, each subsequent draft becomes another going out and return to beginnings, each time seeing yet more clearly what it was that first presented itself to you. How many drafts? How many returns? I think the current catch phrase here is, "Wash and repeat as often as necessary."

Q. Your plays have the reputation of being notoriously unpredictable and original, and now in this novel one of the things I noticed is also just how different this novel's structure is from most novels. Gone, for example, are the usual chapter headings, etc. But what impressed me most was how I was immediately seized not only by the poetic expressive language, but also by the pace of the action. The experience was like watching a movie. How did you achieve this effect, or put another way, is that the effect you wanted to achieve?

A. My instinct was to look at the novel as a playwright would, bringing to it the same skill set and devices familiar to me on the stage to create conflict and drama. Where the novel form is often hugely narrative description yoked to occasional internal reflection and punctuated by bits of dialogue, Infinite Absence cascades on rivers of charged dialogue and internal monologue, only punctuated by narrative description. Also, the lengthy chapter construct of the novel has given way to shorter, more irregular, and unpredictable beats of action whose length is determined solely by their dramatic force. On some occasions these beats of action may go on for extended pages, as in the traditional novel, but in many other instances they may only be a few paragraphs or sentences in length before driving to their climax and abruptly ending.

Q. You've spoken of this novel as "A circumnavigation of the soul from Magellan to P." It's clear that P is Peabody, the central character of this tale, but why is he never given a first name? And what exactly do you mean by "circumnavigation of the soul?"

A. Infinite Absence in some ways mirrors Magellan's archetypal transit through the strait that bears his name and then out across the globe. It's Everyman's soul making its individual voyage of exploration, the risky going out and back into an unfathomable cosmos of sun and shadows in which we bounce from enlightenment to ignorance and back again, and from which all signposts are down and God chooses to make Himself infinitely absent. As for Peabody who signs his letters with a grandiloquent P, and no one speaks his first name, nor does he appear to even have one, each individual will read the book and make up his own mind why that is so.

Q. Why did you choose to publish the four parts of Infinite Absence in two separate volumes all at once rather than four stand alone novels? Many authors "serialize" their novels publishing them separately as soon as each part is completed. Why did you hold off until all four parts were completed?

A. Infinite Absence is one complete story. It's meant to be read one part into the next. Until I reached the end of the very last part of the very last draft and saw that it was all whole could I be sure it was ready for publication. Some philosopher once cautioned artists and writers not to show their work "in embryo." I believe that.

Q. By the way, what was that line that made you write Infinite Absence?

A. It never made it into the novel. For all the effort I spent brooding over that line, when I came back to my starting place after finishing the first draft, I saw that line for the first time, and came to understand it truly didn't belong to Infinite Absence at all.

Q. Wow. That says tons about the writing process---or the lack of a fixed process.

One last question, Ron. You made another major switch in your life sixteen years ago by moving from the Northeast--New York City and South Salem in Westchester--to California and then to Denton, Texas, outside of Dallas. Many would say that's a bigger genre change than switching from playwriting to writing a novel. Did the move to Texas have any impact on your writing, since you wrote Infinite Absence in Texas?

A. Back in the mid-1950's when I was in the Army, I was stationed for half a year or so at Ft. Hood, TX, taking advanced tank training, so moving to Texas is more like a return to an old familiar place. By birth, I'm a native New Yorker, born in the old Sydenham Hospital that used to be up on 125th Street in Manhattan before they tore it down. Most of the rest of my youth I lived in Brooklyn, working every summer as a kid in the amusement parks of Coney Island. New York is filled with wonderful energy, productivity, and a sense of aliveness, not to mention the theater and the arts. But there is so much wonderful about Texas, too.

Q. I sense PR for Texas coming.

A. Well, you can't not live here and feel its pride and "can-do" attitude, its spirit of individuality and self-reliance, the endless construction that's turned its dusty roads into six lane highways and clover leaf masterpieces of concrete architecture, the constant reshaping that is turning this state into a Mecca for cutting edge innovation in science, business, technology and medicine. The old Texas is somewhat gone, but in its place the 21st century has found itself a vital new home for opportunity.

Q. And how does that relate to your writing?

A. Reflecting on all this motion and change, it seems my life, too, has in large part been spent moving around--wanting permanence, and mostly getting motion. Until the time I graduated Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, I lived at 17 different addresses, my family sometimes sharing our series of apartments with less fortunate relatives who were temporarily dislocated, or occasionally moving in with other relatives when the situation was reversed. The impact of Texas on my writing was one more of time than locale. I think, without any conscious will on my part, it was just time for me to lay down the familiar and move on to different challenges.

Q. I'm not going to give away any plot details, but will say that in addition to the elegance of your writing, comments of customers who posted reviews on Amazon capture the essence of Infinite Absence: "a novel that held me throughout... the story line is totally fresh and unexpected ...a fast moving adventure...twists I never could have imagined."

Thanks Ron. In addition to giving us a great read, your courage in taking this new direction might inspire other writers with the temptation to venture into another genre to take the leap.

For more information visit ronaldribman.com.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is professor emeritus at the City University of New York (Brooklyn College) where he directed a graduate program in gerontology that spanned seven graduate departments. He is founder, and for 25 years, the managing editor of the cutting edge Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Starr was also the editor of the Springer Publishing Company series Adulthood and Aging and another series Lifestyles and Issues in Aging. For three years he wrote commentary and op-ed articles on healthcare, the boomers, and issues of an aging society for the Scripps Howard News Service. And for seven years he was writer, producer, and host of the award winning radio feature The Longevity Report on WEVD-AM radio in New York City.