In the early 1940s, Jan Karski was a courier for the Polish underground who snuck into the Warsaw Ghetto and then tried to warn Allied leaders about the Nazi extermination of Europe's Jews. At approximately the same time, Hannah Arendt -- a brilliant philosophy student and refugee from Germany -- was fleeing an internment camp in France, and finally arrived in New York. While each of their trajectories was unique, both became influential university professors in the United States.

I am juxtaposing them because I recently attended two formidable festivals that featured documentaries about these towering individuals. At the 25th Krakow Jewish Culture Festival, Slawomir Grunberg's Karski & The Lords of Humanity was screened inside the restored Wysoka (High) Synagogue--a poignantly appropriate locale for a film about the Polish hero who embodied a "Righteous Gentile." A week later, I was watching Ada Ushpiz's Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt at the Jerusalem International Film Festival. Because it includes her coverage of the 1961 Eichmann Trial in Israel, I was again aware of being in the very country depicted onscreen.

While both films explore a major figure of the 20th century who confronted anti-Semitism, Arendt is far more controversial: she perceived a pervasive totalitarianism that transcends borders, and articulated the menace of all ideologies. For some critics, her book Eichmann in Jerusalem was morally reckless (from the possibly reductive coining of "the banality of evil" to criticism of the Jewish leadership in ghettos); for others, she was ethically restless and succeeded in raising discomforting questions -- including a few about the state of Israel. I could feel audience members around me bristling at the counterpoint of Arendt's term "racist chauvinism" with footage of Palestine in the 1940s.

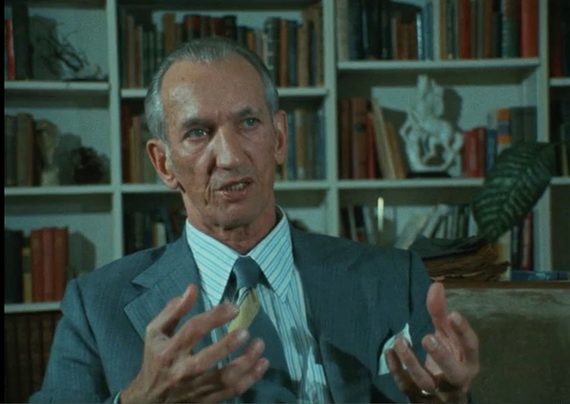

She developed her trenchant provocations in books like The Origins of Totalitarianism. But Karski -- disheartened after the world did not heed his wartime warning -- didn't speak about his experiences for decades. Grunberg's documentary shows him primarily in excerpts from Claude Lanzmann's Shoah (1985) -- where he broke his silence -- while interviews with historian Martin Gilbert and former U.S. National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski assess his legacy in our own time. E. Thomas Wood, author of Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust, says of his former professor, "Karski had an air of moral aristocracy."

Photo: Jan Karski courtesy of: SHOAH by Claude Lanzmann © 1985

Born in 1914 Lodz when it was a multiethnic city, he later escaped the Soviets and joined the Polish Underground in 1939. Twice he infiltrated the Warsaw Ghetto, and tried to warn the American government of the horrors he witnessed. But he encountered passivity: President Franklin Roosevelt feared the possible perception that the United States was entering a "Jewish war."

Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter met with Karski and concluded, "I can't believe you": he was not implying that the courier was lying, but admitting his own inability to absorb the truth. Karski used the term "Lords of Humanity" -- perhaps ironically -- in referring to leaders such as FDR and British Minister for Foreign Affairs Anthony Eden.

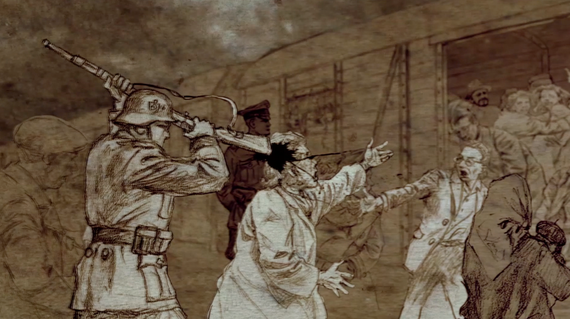

From a script co-written by Katka Reszke, Grunberg visualizes Karski's exploits via animation: in a manner similar to Ari Folman's Waltz with Bashir (Israel, 2008), this distancing technique questions recollection and representation. Given the film's inclusion of archival footage of the Warsaw Ghetto -- propaganda shot by German cameras -- the animated scenes heighten our awareness of how images can be fabricated.

Photo: Animation/Drawing by Tomasz Niedzwiedz

During the q/a session that followed the Krakow screening, historian Michael Berenbaum--who spoke at Karski's funeral in 2000 -- added a memorable detail: "The Jewish community flew over a traditional yellow star, the type that Jews were compelled to wear in the Ghetto as a badge of shame, and asked that it be placed on his chest for burial -- a tremendous honor, a gesture of unparalleled majesty."

Recognized as a "Righteous Among the Nations" by Yad Vashem in 1982, Karski says on camera, "We have infinite power to do good or bad. We have choice." This kind of existential awareness permeates Ushpiz's Vita Activa as well. The opening titles make clear that the Israeli filmmaker has an agenda: Arendt's legacy includes "the dangers of ideology, any ideology," and "the need for pluralism."

Arendt's vision was indeed global, if anchored in her understanding of "right-less" refugees between the wars because she was one herself. She fled illegally to Paris in 1933 and was interned in 1940 at the Gurs camp, but escaped to New York before the German Occupation.

Photo of Hannah Arendt courtesy of Go2Films

Archival footage and interviews supplement her words (voiced by an actress) from letters and books. Unsurprisingly, the most pungent scenes are those of the aged Arendt herself on television, chain-smoking and unapologetic for her analysis.

In 1964, she defines as "banal" Eichmann's inability to imagine what others go through. What Arendt calls his "lust for functionality" was less "demonic" than a failure of the moral imagination to go beyond what one is told -- a danger that can exist in many times and places. While Karski's wartime call for action went unheeded, Arendt's search for a more vigilant awareness continues.

Annette Insdorf, Director of Undergraduate Film Studies at Columbia University, is the author of PHILIP KAUFMAN.