Plastic is everywhere. Not just in our homes and cars and offices - it has moved beyond our garbage bins and can be found littered on our city streets, parks and beaches. As a consequence, we increasingly see it on our beaches and in our rivers, lakes and oceans. There's even disturbing evidence that it's now inside the fish that we eat. I interviewed Dr. Chelsea Rochman, a postdoctoral Smith Fellow at the University of California in Davis and the University of Toronto, about her research on the impacts of plastic debris in fish:

Question 1: What kind of research has been done to indicate that plastic found inside of fish is a widespread problem?

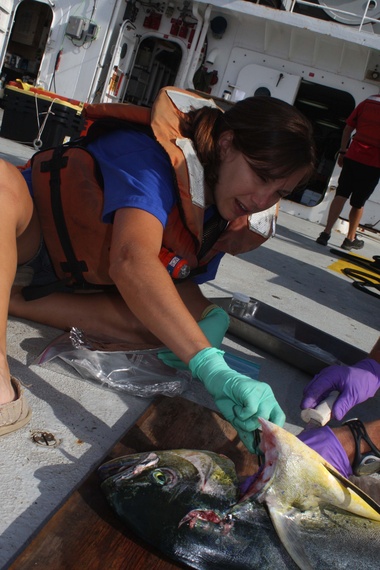

Answer: Scientists have looked inside the stomachs of many different kinds of fish from lakes and oceans all over the world. Besides the usual algae, worms, plankton, fish, etc... we are increasingly finding something a bit more familiar to our own species--plastic. Many of the fish sampled to look for plastic are fished from oceans and lakes during research cruises. Some of these studies pointed out plastic debris in species we consider commercial. We wanted to look a bit closer, asking a more direct question related to these findings: Is there plastic debris in our seafood? To answer this question, my colleagues and I purchased roughly twenty different species of fish from fish markets in Makassar, Indonesia and California, USA. We also purchased one species of oyster from Californian markets. We found plastic and fibers from textiles (e.g., clothing, carpet, fishing nets) in about 1 out of every 4 seafood items sampled. (read the article in Nature Scientific Reports here). Were we surprised? Yes. But why, when we said earlier that plastic debris is found in many species of fish globally? We were surprised because suddenly our findings were directly relevant to us. Our data went straight to our stomachs--the ghost of waste management's past is indeed coming back to haunt us on our own dinner plates.

Question 2: How harmful is this plastic - both to the fish, and to humans who might eat them?

Answer: We know much more about how plastic debris is harmful to fish and much less about how plastic debris in our fish is harmful to our health. Several laboratory studies have demonstrated that plastic debris can harm fish. Plastic can get stuck in the gut of fish and make them feel full, thus changing their feeding behavior. Small pieces of plastic can cause inflammation in organs and tissues. My own research demonstrated that small plastic debris can transfer harmful chemicals to fish, cause stress in the liver and change the activity of genes related to reproduction. For humans, all we know at this point is that there is no doubt we are eating plastic when we eat seafood. Studies have shown plastic debris in shellfish, fish and even sea salt. So, yes, we need more research to answer questions about how plastic debris may impact food security (i.e. fish stocks) and food safety. But more importantly, our results suggest we take our waste management more seriously now to prevent plastic debris from ending up on our dinner plate period.

Question 3: What can be done, realistically, to reduce to flow of plastic into our waters and into the food chain?

Answer: In general, the most effective way to prevent further contamination is to cut off plastic pollution at the source. If we focus only on clean-up efforts, we will be wasting time and money. For example, let us imagine you have a flood in your basement. The pipe from your washing machine has exploded. Where do you spend your energy first, mopping it up or turning off the water? If we focus all our efforts on cleanup, we are not stopping the millions of tons of plastic entering the ocean from land every year (Jambeck et al., 2015). As such, we need to focus our efforts on a diversity of local solutions to this global problem, including building new waste management infrastructure, education and outreach, local environmental cleanup, creating laws that prevent the consumption of non-sustainable single-use plastic items and the innovation of sustainable items that are less likely to become persistent plastic pollution. Together, these efforts will help ensure cleaner oceans and seafood for future generations.

Question 4: I understand you also research the impact of plastic microbeads from facial scrubs that go down the drain and end up in the oceans. Why are these a threat?

Answer: Plastic microbeads are one of the many sources of plastic pollution that are found in hundreds of species of wildlife. These tiny beads, which are added to our facewash, bodywash and toothpaste as abrasive scrubbers, are particularly problematic because, by design, they are more likely to enter the ocean than many other forms of plastic. These tiny beads rinse off our bodies, go down the drain and travel to the wastewater treatment plant in our city. There, they either settle into the sludge or remain in the final effluent--the cleaned water that is sent directly into streams, rivers, lakes and oceans. Wastewater sludge is often applied to land as fertilizer. During rainstorms, runoff from land flows back into aquatic habitat, carrying some of the microbeads with it. Our own estimates suggest that at present, roughly 3 trillion microbeads enter aquatic habitats in the United States every year. This is enough beads to wrap around the Earth more than 7 times when lined up end-to-end. That's a lot of beads! Thus, removing these from our daily products prevents a lot of plastic from becoming plastic pollution.

Question 5: Do you think the recent congressional vote to ban microbeads - a rare act of congressional unity - goes far enough?

Answer: I think the recent vote to ban plastic microbeads from all rinse-off personal care products in the United States is a major victory. It is one of the many steps necessary to prevent plastic debris from landing in our oceans. There are a couple of things that are special about the Microbead Free Waters Act: 1) it is bipartisan; 2) it won with a unanimous vote; and 3) environmental activists and industry both support the legislation. This bill demonstrates how important this issue has become to all our members of congress and their constituents. It also demonstrates the recognition of plastic pollution as a contaminant of concern in the United States, which is a critical step for future prevention and cleanup. As such, while this bill may not ban plastic beads from all personal care products, it likely will open the doors and carve a path toward more funding for marine debris research and further mitigation strategies for prevention and cleanup of persistent plastic pollution.

Dr. Chelsea Rochman is a Marine Ecologist with emphases in Marine Ecology, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Chemistry. Her overarching goal is to use objective science to inform positive environmental change. She is currently a David H. Smith Postdoctoral Fellow in Conservation Biology working at UC Davis and at the University of Toronto. Her main research focus has been about the implications of the infiltration of plastic debris into aquatic habitats. Her work has asked questions about the sources fate and toxicity of plastic in aquatic habitats.

Tim Ward is co-author of The Master Communicator's Handbook. "Communications: it's not about output, it's about impact."