American journalist Christian Parenti and his Afghan interpreter travel to southern Afghanistan to conduct an important yet very dangerous interview with members of the Taliban. The moment comes when the men fear the interview may turn ugly, and they quickly grab their belongings, jump into their taxi and race off. In the car, Parenti asks his fixer, Ajmal Naqshbandi, if he will tell his fiance about the interview. Hell, no. The men laugh. Telling the fiance would be more dangerous than meeting with the Taliban.

In another scene, the documentary flashes forward six months, and the same fixer, Naqshbandi, stares into the camera but this time without the look of the jovial young man who was laughing in taxis and eating dinner with friends. Naqshbandi has been kidnapped, and his lighthearted expression has been replaced with one of fear. Sweat drips down his cheeks as he tries to reassure his family that everything will fine.

By juxtaposing scenes of laughter and friendship with video images of kidnappings and beheadings, HBO's "Fixer: The Taking Of Ajmal Naqshbandi," directed by Ian Olds, uses the relationship formed between an American journalist and his interpreter to tell the story of the war in Afghanistan.

The HuffPost sat down with Parenti to talk to him about the film, modern war reporting and why he thinks Obama's current Afghan policy is bound to fail.

How did you find Ajmal, the fixer in the film who is kidnapped and killed?

My friend Teru Kuwayama is a photographer with whom I did a book from Iraq who went to Afghanistan right after the invasion. And he met Ajmal, when Ajmal was basically working front desk at somebody's guest house. Here's this kid, who at that point was really a kid, who spoke perfect English and Teru was like, "You can make a lot more money as a fixer."

When you go to a place where you have no connections, you don't know anybody who's ever worked there as a journalist, you don't know anybody in any aid organizations or anything, and I've been in situations like that, the best thing you do is go to the local college, and you find the English department, and you try and find some bright, ambitious, young person who's interested in working as a fixer.

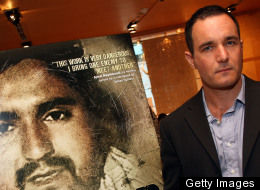

Journalist Christian Parenti attends the HBO Documentary Screening Of 'Fixer: The Taking of Ajmal Naqshbandi' at Asia Society on August 12, 2009 in New York City. - Getty Images

Have you ever worked with a fixer who was a spy, or who worked for the government or had interests that weren't aligned with yours?

No, but in Iraq you would basically have to have a Shia fixer and a Sunni fixer.

If the fixer is a Ba'athist, you know what the line is going to be, you know what the spin is going to be, so the source and fixer have the same kind of point of view. It's not that the information is never distorted, but you know the fixer is at least going to tell you what the person is saying. Whereas if you took a Ba'athist who hated Shia to some Shia neighborhood, they could very well start distorting what the person is saying to you.

Do you consider a fixer a journalist, and does it matter?

I don't know if it matters particularly. It's semantics. If you don't want to call a photographer a journalist, or if you don't want to call a TV producer a journalist, then don't call a fixer a journalist. But if you have a broader definition of a journalist as people who produce the news -- editors, fixers, producers, photographers, sound people -- then a fixer is a journalist. Certainly the task of a fixer is very much like a producer on a television program. [A fixer is someone] who arranges things. They work with the reporter.

How does Ajmal compare to other fixers you've worked with?

In many ways, he was the most professional, the most ambitious, and the most together fixer that I ever worked with. And he was active in the Afghan journalist association. After the invasion a lot of money went in ... to build up civil society. So there was a lot of money for journalism in Afghanistan. And out of that came some pretty decent, strong Afghan journalist organizations.

Scattered throughout the film are scenes of Taliban kidnappings and even beheadings. Where did you find the video of these?

A lot of it was online, a lot of it was on DVDs.This propaganda is everywhere in the bazaars. The Taliban produce their own media. Video equipment is cheap, the Internet allows you to distribute things practically for free, and they don't really need journalists the way they used to. They don't need foreign reporters to get their message out. They can get their message out on their own.

So they are citizen journalists?

Yes, they are citizen journalists with AK 47s. They produce this terror propaganda. It's part of what they do and so, far from that being exclusive, hard to find, they're doing everything they can do to get that into people's hands. So it was actually pretty easy. And then there were numerous different sources. We used the internet, we bought a whole bunch of weird DVDs from shady people.

As you discussed after the HBO screening, the original idea for the documentary was a film about the mechanisms of war reporting. Olds traveled around Afghanistan with you and Naqshbandi, filming your interactions for this purpose. But as the film was being made, the Taliban kidnapped Naqshbandi. You and Olds said you almost abandoned the film entirely. Instead, you decided to return to Afghanistan, investigate the kidnapping and killing of Naqshbandi and ultimately tell his story.

The fact that Ajmal dies inherently makes the film more compelling and dramatic. Given that he was your friend, how did you grapple with that?

Because we were his friend, and we had this intimate footage, there's a responsibility to not make a exploitative, cheap film but to use this footage that we had accumulated to make something meaningful that would reach a large number of people, which we've done, by having it on HBO. We're reaching a lot of people.

I see it as an obligation. We try to honor Ajmal and also all the fixers who mostly labor unrecognized and at great risk.

War has defined a lot of the politics in the Bush administration and still does in the Obama administration... Journalism and war reporting and foreign reporting became a vaunted career that was a focus of so much attention, in a way that I had never seen before. And it was like, in a way, a hey-day of foreign reporting under the Bush administration. So our culture and our politics over the past eight years were really defined by these wars ... and in that fixers were absolutely essential and really have not been explored and honored as characters and as laborers and as workers in the war zone.

Did Ajmal's death affect the way you work with fixers?

Not really. There's a simplistic version of what the relationship is between a journalist and a fixer -- that the journalist has all the power and the fixer just works for him. But it's not like that. There's a lot of negotiation. And back and forth. And just as journalists pitch stories to editors, fixers pitch stories to journalists.

Earlier this week, Obama said the war in Afghanistan is necessary to U.S. security. Do you agree?

No, I think that Obama's escalation of the war in Afghanistan is probably undermining U.S. security. The Afghan government is totally corrupt and populated by drug dealing warlords and is going to be incapable of functioning as a real state. And the escalation in the name of bolstering this government is succeeding in widening the war into Pakistan, and we've seen what the effects of that has been. These drone strikes, these aerial strikes, though they have killed Baitullah Mehsud, they have also engendered tremendous outrage amongst the Pashtun people along the border, and now Pakistan is much less stable than it was.

I think that the only real [option for better security] would be a grand bargain in which all of the problems of the region are put on the table, and there's some sort of long-term, huge negotiations at which all of the states that are parties and proxies to these fights -- meaning, everybody from Israel and Saudi Arabia [to] Russia and China and India -- are all sitting down and dealing with all these questions.

What impact do you think the Afghan presidential election will have?

[Afghanistan] is so unbelievably dysfunctional and such a violent political culture - so riven with drugs, corruption. If one guy becomes president who happens to be a decent guy, he's not going to be able to change that much because he's up against this class I described of warlords. There are 32 ministries. These are like 32 barons... This class is powerful and cannot be overthrown by one presidential election. And there is nowhere near the faith in change amongst the Afghan people that there is amongst the Iranians. People are really, really beaten down there.

It's deadly when you have the best and the brightest of the next generation, men and women in their 20s, who want to participate and do stuff, who are like, "Ok, forget it. I want to get out of here, I want to go to Pakistan or Sweden or whatever."

I'm very cynical about this election doing much besides being a stamp of approval.

Fixer: The Taking Of Ajmal Naqshbandi premiered on HBO on August 17. For the HBO schedule, go here.