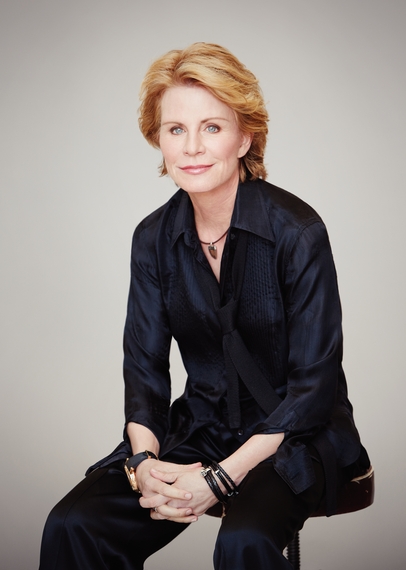

Photo credit: Patrick Ecclesine

Patricia Cornwell is the internationally bestselling and award-winning author of 33 books, the most famous and widely read being the 22 novels of the "Kay Scarpetta" series.

In Flesh and Blood, Kay Scarpetta notices seven shiny pennies, all dated 1981, placed on the wall behind her Cambridge house. She soon learns of a shooting death nearby, where copper fragments are the only evidence left at the crime scene. Scarpetta links the murder to two other deaths in which the victims were killed by a serial sniper. The victims had nothing in common, but seem to have a connection to Scarpetta herself.

You were a technical writer and computer analyst for the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of Virginia. Your Kay Scarpetta novels are so richly detailed in medical forensics, it's hard to believe you're not a physician. How did you learn so much forensic pathology?

People mistakenly call me 'Dr. Cornwell.' I was an English major in college. For thirty years, I've been a self-educated student of medical forensics, ballistics and all things related. It's my avocation. I constantly cruise the Internet looking for new information. I have consultants on whom I rely for the latest technologic advances. I also do field research. For Flesh and Blood, I went to Texas firing ranges to test high-tech assault rifles and ammunition, the things you'll read about in this book. That's how I continue to learn. While I would not qualify as an expert witness in court -- I don't have the pedigree -- there's nothing to stop me from educating myself.

Did you ever want to become a physician?

No. I'd rather write about a Scarpetta or Lucy or Marino than do what they actually do. I'm a writer first and foremost. Before writing fiction, I was a journalist. My background puts me in a good position to write about and let the world see what these really cool professionals do.

Your Kay Scarpetta novels have influenced TV programs such as CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, and Cold Case Files. Do the television writers ever ask for your advice?

I don't really want to be a consultant on other people's shows. However, I'm writing a pilot for a CBS show called Angie Steele. It's about a woman investigator who went to MIT, but decided to become a cop. So, I'll be a consultant for that show, but I don't have an interest in consulting for other shows.

Your writing style has varied in the Scarpetta series -- from past to present tense, from first person to omniscient narrator, and you've gone back and forth. What brought about those stylistic changes?

I think a writer looks for different ways to explore abilities and skill sets. You always want to evolve, and my goal has always been to get better at writing. I'm constantly exploring different ways to do it. In writing a series, there's a lot of latitude for experimentation, opportunities to stretch your wings. In 2003, with Blow Fly, I switched to a third person point of view. The fans didn't like that. They wanted to be inside Scarpetta's head. I write these books for my readers. So, I switched back to the first person point of view. I'm quite sure I'll continue writing in the present tense. I've always thought of writing as a glass window pane through which the reader enters a new world. I try honing my writing style to be as immediate, physical and tactile as possible, almost like the reader is watching television.

For me, the present tense lends immediacy to the work, makes it almost cinematic. The great challenge for writers is to draw the reader into the novel, as though it's a movie. When you're reading, the brain must translate printed words into sights, sounds, smells and taste; whereas you don't have to do that as much in movies. That form gives you an immediate emotional response. The limbic system is on fire when you're watching a movie or when you're at a rock concert. When reading a book, the brain has to do the work of getting the reader to that place. So, I do whatever I think is necessary to help the reader make the transition to those emotional responses. In a sense, you can call me an emotional facilitator (Laughter).

Conflicts between Scarpetta's associates--in Flesh and Blood, between Marino and Machado--often occur. What's the reason for this?

Police are people. They get competitive. I often see investigations where detectives don't collaborate well. You're dealing with human beings, so this sort of thing happens. The biggest bear trap in police work is having multiple jurisdictions working on a case. It's not always the seamless collaboration you wish would occur. But that's true in non-law enforcement workplaces, too--in the academic world, hospitals, law firms--actually, it happens anywhere. It's like any family: there are rivalries.

What do you think so fascinates readers about forensic work?

I think it's the same thing that's so fascinating about archeological excavation. Or, your own discoveries when you find an object like an old arrowhead buried in your backyard. You start recreating the scenario of how that object got there. Why is it here? What happened? Did someone live or die on this very spot? Our human nature demands that we be intensely curious about these mysteries and try piecing together our surroundings so we're better informed. That's what forensics is all about.

To me, this goes back to our tribal survival instincts. If you can recreate a situation in your mind about what happened to someone, how that person died, there's a better chance it won't happen to you. I think it's part of the life-force compelling us to look death in the face. We're the only animal with an understanding that someday we'll die. I think we all want to make our temporary stay on this planet less mysterious, more knowable. We want to learn what happened here, so we'll feel less vulnerable about the same thing happening to us. It's the kind of curiosity that propels us to study monsters.

More than 100 million copies of your books have been sold; they've been translated into 36 languages and are available in 120 countries. After all this success, what has surprised you most about writing?

What's surprised me most is the very process of creativity. I've been fascinated by where ideas come from. I feel when we really open ourselves up to our urges and get our conscious brains out of the way, we're almost channeling things from areas we don't begin to understand. It's both a scary and amazing experience. I've been repeatedly surprised how secret parts of my mind are creating something without my conscious knowledge. Hemingway was very aware of this phenomenon. He had an ironclad habit: when he had written a very good sentence and knew where he was going next, he would quit writing and not think about it until he went back to it the next day. He wanted to give his sub-conscious mind enough time to work on the story. That continues to surprise and amaze me: this ability the human mind seems to have. It even goes to the issue of genetic memory. We channel things creatively that really come from someplace that's part of our genome, our primal heritage.

What do you love most about writing?

I love the way it keeps me company. I find no matter what's going on in my life, I don't have to wait on somebody else to fill my time or give me satisfaction. If I have an hour or two, I can sit at my desk, open something I'm working on and be transported to the same world I want to take the readers. I probably developed that ability for a very good reason. As a child, writing was my best friend. If I wrote a poem or an illustrated short story, or described the scenery while I looked out over a valley in North Carolina where I was brought up, it made me feel less by myself.

I think being on this planet is a lonely experience and without imagination, it's very isolating. For me, writing has been a gift. Creative expression is a great coping mechanism. If you're sad, scared or lonely, much as I was as a child, writing was my retreat. I played sports and all that, but the thing that healed my soul and touched those parts of me nothing else could, had to come from within myself. If you can reach inside yourself and create something--a painting, a drawing, a book-- it can be healing and very life affirming.

Who are the authors you read these days?

I'm an eclectic reader. I read a lot of biographies. I love non-fiction, especially history. In fiction, I enjoy reading Lee Child, Dan Brown, Michael Connelly, and Harlan Coben. It has to be something very engaging; otherwise, my attention will wander.

If you could have dinner with any five people, living or dead, from history, politics, or literature, who would they be.

I'd love to have dinner with Dickens. I'd love to have dinner with Agatha Christie. I'd love to have met Lincoln. I'm so sorry I never got to meet Truman Capote. I think In Cold Blood is one of the greatest true crime books ever written. I think dead people might be my specialty (Laughter). And then there's Harriet Beecher Stowe. She's supposedly a relative--allegedly, an ultra-removed aunt of mine. It may be part of my genetic heritage, because she and I write basically about the same thing: abuse of power, whether it's slavery or anything else. I visited her home in Connecticut and can honestly say I felt a kinship, something almost akin to channeling something from her.

What would you be talking about at dinner?

I'd be fascinated about their writing processes. I'd love hearing how they started their days and the things that compelled them to write what they did. I know Dickens was influenced greatly by his childhood--working in a bootblack factory by the age of twelve. It would be fascinating to talk with Agatha Christie. I understand she was incredibly shy and introverted. Becoming a celebrity was difficult for her because she was happiest staying at home and writing. Also, both Dickens and Agatha Christie were heavy into research, so we'd have a great deal in common. If she were writing today, who knows? Miss Marple might have been a medical examiner.

What's coming next from Patricia Cornwell?

I've started the next Scarpetta book. I'm finishing the remake of my Jack the Ripper book. I'm also writing the pilot for the CBS series, Angie Steele. It's about a woman investigator who has a fraternal twin brother who's a sociopath, and she's very worried about having a child because of what her genetic heritage might entail.

Congratulations on penning another Kay Scarpetta novel, Flesh and Blood. It's certain to keep your fans very happy.

Mark Rubinstein,

Author of Mad Dog House, Mad Dog Justice and Love Gone Mad