After getting revived with naloxone from a near-death experience, people find there are neither affordable nor appropriate treatment options for opiate addiction.

By Hyun Namkoong

James Sizemore, a community pastor in Fayetteville, North Carolina, lets out a loud sigh and shakes his head in frustration when he talks about the inadequate resources available for substance addiction and the numerous obstacles that stand in the way of getting help for the people he serves.

Sizemore quickly rattles off a list of barriers that span from lack of health insurance coverage, unaffordable treatment options, long waiting lists and what he calls the Catch 22 of treatment, work, detox and the criminal justice system.

"People who really want and need help have a very difficult time getting housing, employment or other services due to a criminal record or lack of money. So they stay on drugs, get caught up in the legal system, and it starts all over again in an endless cycle," he said.

The problems in Fayetteville reflect what has been unfolding nationwide ever since the resurgence of heroin and the soaring use of prescription painkillers such as Percocet or Vicodin. Although these drugs have claimed thousands of lives in the U.S., healthcare resources and services have failed to catch-up to meet the demands for opiate treatment programs.

"Nobody seems to be noticing that this is a national epidemic," said Les Quagliano, clinical team lead for Greensboro Alcohol and Drug Services. "There are so many people dying."

Rather than strengthen and increase access to opiate treatment services, several state governments have taken actions to do the opposite, such as Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner's recent veto of a bill that would have expanded Medicaid coverage to include treatment for opioid addiction.

"We get the same amount of funding every year from the state," Quagliano said.

"The community is flooded with drugs, but not with treatment," Sizemore said. "What are we supposed to do?"

Unaffordable treatment for minors

Treatment options available to minors are even more scarce and piecemeal, something parents may find troubling considering the FDA's recent decision to approve the use of OxyContin for children as young as 11.

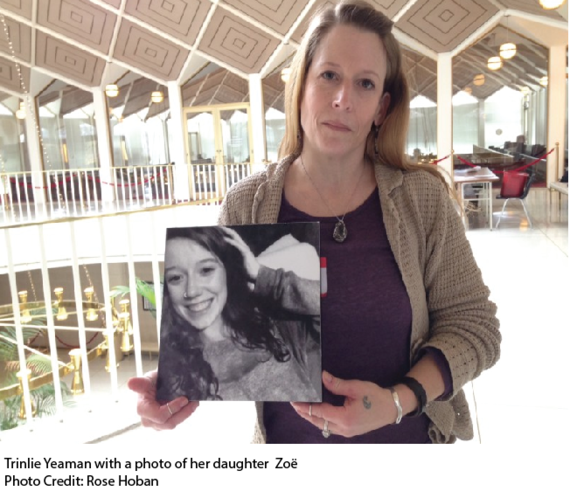

Like so many faces of the heroin epidemic, Trinlie Yeaman's then 17-year-old daughter Zoë first started using pain pills and later turned to heroin, a cheaper and more easily acquired drug. Yeaman exhausted numerous resources and tried multiple avenues to get Zoë into treatment only to run into bureaucratic, legal or financial barriers for getting Zoë the help she needed.

To get into treatment, one must first check into a detox facility, and that's where Yeaman encountered first of many hurdles for finding appropriate care for her daughter.

"There weren't any detox facilities for adolescents at the time," Yeaman said. "There are eight beds in Asheville. It's not enough."

The U.S. Census estimates that 89,000 people live in Asheville.

Yeaman's insurance company then wanted her to pay $40,000 up front for a stay in a private detox facility for adolescents and Yeaman even tried to re-finance her house to foot the bill, but she wasn't able to do it fast enough.

Zoë died from an overdose on August 6, 2014.

"The resources just aren't there [for substance abuse and addiction]. Even in a hospital, they kept telling me, we're a mental health facility," Yeaman said. "We really need better services."

Waking up dope sick

Continued heroin use leads to an increased tolerance and a dependency on using it to avoid the effects of withdrawal. Many people may want to stop, but withdrawal symptoms that range from extreme pain in muscles or bones, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and insomnia make it an uphill battle for recovery.

"When you wake up [from naloxone], you're extremely dope sick," said Caitlyn Phillips, a resident of Asheville who used intravenous heroin for several years. "It's the most painful way to wake up."

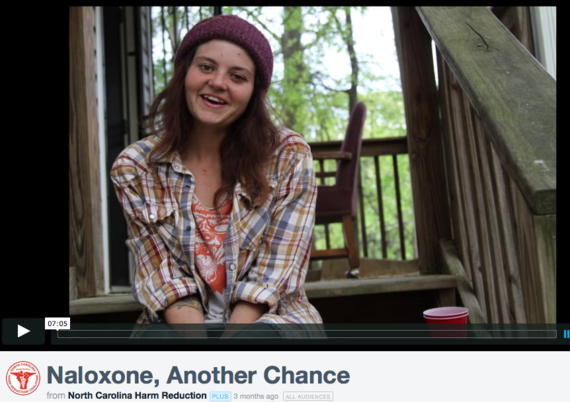

In the short film, Naloxone, Another Chance, Nicole, a young woman from Alabama shares the difficulty of stopping drug use even after overdosing and receiving naloxone.

"I'm still continuing to use, not because I love it or I want to," Nicole says. "Right now, it's due to the sickness, just to maintain."

Phillips said for some people it takes more than the overdose experience to make a change and seek help.

"For most addicts, the lifestyle really wears you down. That's what people get tired of," Phillips said. "It's exhausting...The stress of using, hiding from the people you love, hiding from the police, trying to get enough money, get drugs. You don't have hobbies anymore, family or a job. A person can't do that for very long and still want to continue."

There are numerous factors that can push or pull people to go down the path towards recovery and treatment.

Amy Garner, long-time director of Carolina Treatment Center, emphasizes the importance of viewing addiction as a disease that is not curable, but treatable.

"During the course of someone's addiction, as in any disease, there are periods of progress, remission and recovery," Garner said. "There are also periods of lapse and relapse, when the disease flares up and takes control. Addiction is a terrifying brain disease."

Inappropriate treatment

Unbeknownst to many people outside of the rehab world, the 12-step program goes far beyond the famous line parodied in movies and pop cultures, "My name is John and I have a drinking problem."

When Phillips was ready, she checked in to a 12-step in-patient rehab because that was the only kind of treatment available in North Carolina that didn't have a price tag of $40,000.

The 12-step program is guided by overtly spiritual and religious principles that include steps such as require attendees to make a moral inventory of flaws, admit and repent of your wrongs to God and others and the final 12th step is to carry the message to other people who are addicted to drugs.

People who don't believe in religion or a higher power find this approach ineffective and inappropriate.

"Every professional treatment provider only ever talked to me about a 12-step program and it was just never helpful for me," said Conner Adams who used intravenous heroin for six years.

"I was feeling suicidal over why 12-step wasn't working for me. It was confusing and I tried really hard to be spiritual or religious, but I don't think it works that way," she said.

Adams described 12-step meetings as something that more closely resembled religious services that involved holding hands and saying the Lord's Prayer rather than a therapeutic treatment.

"It's so outdated. The 12-step program was founded in the late 30's and that's our standard of care for addicts today," Phillips said exasperatedly.

"It never occurred to providers that maybe the 12-step program wasn't appropriate," Adams said.

Phillips suggests alternatives to 12-step programs that she believes would be more effective.

"There are so many possibilities and we should be surrounding people like this with community, love and support," she said. "We should be supporting them with every other different recovery avenue until they get better. Hopefully we're on our way, but this is just the beginning."

"The need for more affordable and appropriate treatment options is definitely there in the community," said Robert Childs, executive director of the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. "Passing out naloxone is absolutely important to saving lives and preventing death, but more has to be done to improve the community's capacity to provide care."

If you need naloxone, please contact the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition and we will make sure you receive another free kit.

You can also contact SAMHSA @ (877-726-4727) for more information on treatment options near you.