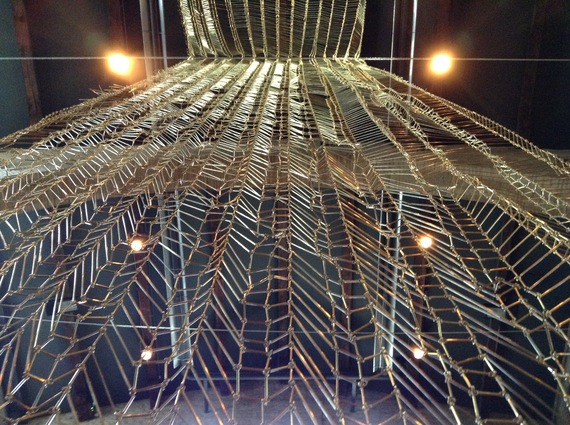

For those who hold out hope of finding a magic carpet spun of gossamer gold, look no further: it hangs from the beams of a grand light-flooded port warehouse, Bordeaux's Museum of Contemporary Art.

Catch a tram ten minutes away to the regional Musée d'Aquitaine, however, and you'll find yourself entombed in another sort of magic, the unending savage war that has engulfed the paradisiacal jungles of Colombia for going on four decades and still shows little sign of ending.

These two winter exhibitions capture the polar promises of the two worlds all of us now inhabit: the first comes from Leonor Antunes a master textile and metal weaver--her carpet is not really gold but shimmering brass wires--and the second is a collection of brutalist--or amateur if you like--collection comes from ex-guerilla murderers working through their nightmares.

Leonor Antunes, born in Portugal, has worked all over Europe but especially in Brazil, exploring what she sees as the classical relation between the human form and the many textiles--or weavings--that surround us day in and day out. If her training is in classical sculpture, her inspiration, she says very often comes from the indigenous weavers of South America.

"Recently I have been looking at the ways certain indigenous tries in Brazil are weaving different materials, how they manipulate and produce volume within different densities and purposes. The Xingu tribes, in Mato Grosso, which I am visiting this year, are still using their traditional techniques, and working with natural fibres that they cultivate in their region," she writes about her current show. She is particularly fascinated by handcrafted mats that "can literally expand infinitely in space, in all directions, building a structure with no apparent limits or end."

The screens, nets, even the floor designs that take over this former port warehouse where slaves were once shackled to the walls, speak to her and to the visitors who go there of the intense rhythms that still burble out of Amazonian Brazil and its architectural and industrial modernity as an emerging global power. To fully see and feel them requires a quiet period of prolonged meditative watching.

The green jungles and overgrown settlements on the north of the Amazon in Colombia, where Gabriel Garcia Marquez spun out his famous literary masterpiece, A Hundred Years of Solitude, remind us with brutal force that can surface when power, greed and ideology overwhelm the artfulness of indigenous design. Called La Violencia during the Liberal/Conservative civil war between 1948 and '58, promoted in part by the U.S. Government's Cold War obsessions, the blood-letting took away the lives of at least 300,000 people and then re-emerged in the 70s as a Narco-Guerilla war among roaming bands of para-military killers, revolutionary squads and Colombia's own military forces. More than 5 million people have lost their homes.

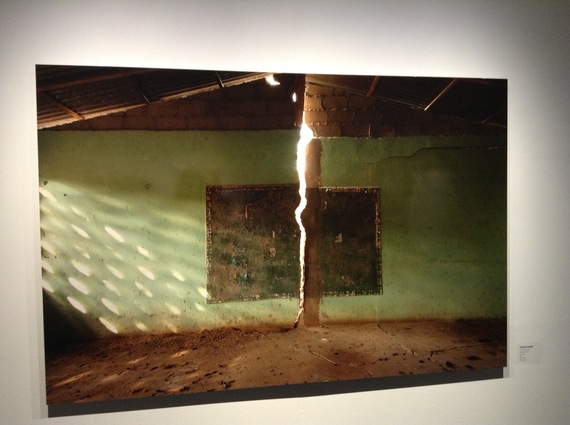

The exhibition at the Musée d'Aquitaine has two parts: the paintings and tapestries made by the guerillas and their victims, and a series of large, rich photographs of school houses that have been abandoned in the wake of "The War We Haven't Seen," many of the buildings literally eaten by the jungle vegetation. The 17 photographs were made by Juan Manuel Echavarria, a man well past 60 who trudged through the outback both to document what had happened to the schools and to work with the mostly men who made the paintings.

By far one of the most striking images is signed simply "Juan," a former government fighter. It is titled "My First Dismemberment."

"Sometimes," he told Juan Manuel Echavarria, "you keep it inside yourself [but] when someone gives you the opportunity to talk about it, it's as if your burden has been lightened."

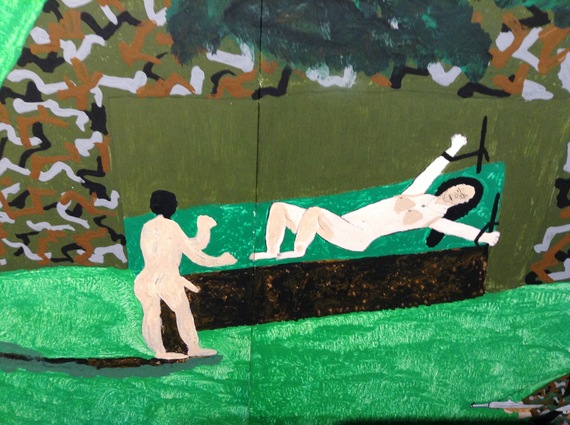

Another para-military ex-fighter, "El Sueco," who joined Colombia's para-military forces at age 18 (the same age that many young jihadists joined ISIS) depicts how he tortured people to extract confessions. He made the painting, in which the action seems to take place on a forest framed stage set, in black and white, he told Echavarria, because it was the only way to capture his sadness over what he had done to an opposition guerilla: "He was a human being and I imagine that he had a family. It is always hard to recall those things...you feel a great void in your heart. Remorse. Remorse."

Hangings and rapes are omnipresent--as in this image by a young man who joined the fighting at age 16 and calls himself "Caliche."

Decapitations, dismembering, slow shooting in the outer limbs until the victim begs to die, teachers assassinated and their schools turned into indoctrination centers by one armed force or another, all surrounded by an otherwise peaceful jungle: these are among the stories recounted in several dozen almost chromatic paintings. All the paintings exist because Juan Manuel Echavarria mounted a project from 2007-2009 to draw the grief-riven former fighters to express themselves in paint. The tradition follows at once the arguments and tradition of Jean Dubuffet, who argued fiercely that "academy art" had lost the capacity to draw deeply inside the artist's soul and expose the myriad ecstasies and terrors that lay hidden within. More recently, the Outsider Art movement has even further advanced Dubuffet's brutalist style to force us all to rip away the skin of formalism, to see, hear, feel the global passions that are engulfing us.

Each in their own ways, Echavarria's unending silent war and Antunes's filigree screens and shadows, propel us into world's that we must see and might at the same time hope for.

All photos of exhibits by Frank Browning