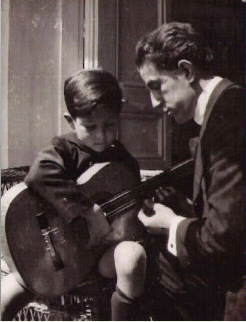

Tarragó's folksong arrangements are colored by flamenco and infused with "duende," the heightened emotional/spiritual connection that exists in the realm beyond technique -- what could be loosely translated as "soul." (Photo by Carlos Saura)

Music informs identity. The little tune that floats into a window from the street below, the lullaby that vibrates in a low hum from a nearby room, the half-remembered refrain of a long-ago lovesong -- these souvenirs-in-sound tell us where we are from and where we are going. And in sharing our songs of joy, loss, sorrow and hope, we discover our most primal bonds and connect with who we really are.

Composers have long taken inspiration from homegrown tunes. Haydn and Beethoven published hundreds of folksong arrangements, and the Romantic symphonists -- Brahms, Bruckner, Tchaikovsky et al -- breathed new life into the symphonic form through their use of regional music. In folksong, they discovered the sinuous, singable melodies and bracing rhythms that refreshed their compositions like so many country breezes.

During the first decades of the 20th century, classical composers intensified what Australian composer/arranger Percy Grainger called their "folk-fishing trips." With industrialization eroding rural identity, composers tapped their musical roots and began to notate what had been a purely oral tradition of cradle, campfire and countryside. Dvořák, Britten, Bartók and their peers ushered in a nationalist music movement that fused the folk and the classical, preserving what globalization threatened.

Fernando Sor (1778-1839) was the first in the great line of Spanish guitar maestros and, like Tarragó, he collected and arranged various folksongs. He also had fabulous muttonchops.

Graciano Tarragó (1892-1973) was among these 20th century composers who mined their countries' musical gold, in his case against the backdrop of Franco's Spain. A teacher, performer, composer and arranger, Tarragó was part of the lineage of Catalán guitar maestros -- from Fernando Sor to Francisco Tárrega to his own teacher, Miguel Llobet -- whose contributions elevated the guitar from a humble "tavern accompanist" to a solo instrument deserving of dedicated study and nuanced composition. His studio at Barcelona's Conservatorio del Liceu nurtured a generation of Spanish musicians that included his own daughter, the virtuosa Renata Tarragó, and the young soprano Victoria de los Angeles. Working within the standard European Late Romantic aesthetic of his youth, Tarragó mined Spain's two particular motherlodes: its early music treasury and its rich folk tradition. From these complementary veins, he forged an inimitably Spanish musical voice.

Celestial jam session: detail from a mid-16th-century Spanish painting by Juan de Juanes featuring the vihuela, Tarragó's Renaissance instrument of choice.

For Tarragó, who played Renaissance vihuela in addition to guitar, early music was an artistic touchstone. The musicologist Felip Pedrell had recently recovered the compositions of Renaissance master Tomás Luis de Victoria (a.k.a. the "Spanish Palestrina") and his contemporaries, offering new clues to the origins of Spanish musical identity and influencing Tarragó profoundly. The perfectly balanced contrapuntal and harmonic elements of these early works spoke to Tarragó's innate clarity of style and his pedagogical impulse toward efficiently honed technique. In arranging these pieces, Tarragó found "a purity of musical structure," to quote his student Jaume Torrent, that demanded utmost tonal clarity and focus. Like Bach arias, these works locate their magic, as well as their difficulty, in their deceptive simplicity.

By contrast, Tarragó's folksong arrangements offer the more extroverted, fiery elements we typically associate with Spanish sound: infectious rhythms, exotic flamenco scales reminiscent of their Arab origins, improvisatory flourishes. Many of these pieces are colored by flamenco's cante jondo (literally, "profound singing"), their vocal lines soaring and plunging to express praise, longing or desire. They are infused with duende, meaning, loosely, "soul" -- the heightened emotional/spiritual connection that exists beyond technique and is said to be the essence of Spanish artistic expression. In Tarragó's folksongs, we experience, in the words of Albéniz, something "of the people, our Spanish people... color, sunlight, flavor of olives... like the carvings in the Alhambra, those peculiar arabesques that say nothing with their turns and shapes, but which are like the air, like the sun, like the blackbirds, like the nightingales in the gardens..."

My grandfather, Adolfo "Doe" Zamora, worked long hours in a refinery, but after work, he cleaned up well and serenaded my grandmother with the folksong, "No me mates con tomates." The tune was silly but had its charms, apparently; she gave him seven kids.

My own journey with Tarragó began several years ago on a hot afternoon in Madrid when, taking refuge from the midday sun in a dusty music shop, I stumbled across some out-of-print folios. My Spanish-Texan-New-Yorker self recognized in the yellowed pages certain essential parts of my own musical makeup: the canciones my father sang to me as a child while accompanying himself on his guitar, the stories of my grandfather serenading my grandmother in his sweetly scratchy baritone, my first classical recording of Victoria de los Angeles singing zarzuela in her crystalline soprano (her family hailed from the town of Zamora, allowing me to imagine her my angelic distant cousin), a certain Spanish light-dark sensibility built into my voice as it is into my DNA... The more I learned about Tarragó -- unmentioned in the history books, an unsung hero in so many senses -- the more I was reminded of how we all carry within us those who came before, and how music informs identity, again and again.

In Tarragó's simple, exquisite setting of the 16th century song "Si la noche se hace oscura" ("If the night grows dark"), a woman calls to her love, pleading to know why, hour after dark hour, he fails to come to her. Her confusion and grief pour out in her ascending melodic line, a rising sob as inexorable as nightfall itself. It is a song of heartbreak and withdrawal. In Tarragó's expert hands, it is also a song of restoration and the return to wholeness that is made possible through the self-soothing act of singing. Through song, Tarragó seems to say, we are restored to the people and the places we love; we are restored, ultimately, to ourselves. In singing, we honor our heritage, our loves, our teachers, those we've lost -- and we reconnect with who we really are. Aun si la noche se hace oscura. Even if the night grows dark.

Camille Zamora and Cem Duruöz perform "Jaeneras," arranged by Graciano Tarragó.

This post is part of a series produced by The Huffington Post as part of Hispanic Heritage Month. For more, click here.