In New York City, there's a street where you can stand before the childhood home of a man who said, "If this is the best god can do, I am not impressed."

The words belong to glorious George Carlin, of course, the man perhaps best known for his monologue about the Seven Words You Can't Say On Television. Carlin was also well known for his contempt for the world's religions. "I've always drawn a great deal of moral comfort from Humpty Dumpty. The part I like the best? "All the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't put Humpty Dumpty back together again." That's because there is no Humpty Dumpty, and there is no God."

There's also a street where you can stand before the place where one of our greatest religious thinkers was baptized, a man who asked, "Why do we spend our lives striving to be something we would never want to be, if we only knew what we wanted? Why do we waste our times doing things, which, if we only stopped to think about them, are the opposite of what we were made for?"

These insights belong to Thomas Merton, Christian mystic and Trappist monk, the author of The Seven Story Mountain. It was Thomas Merton who had an epiphany on the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville, (a spot now marked with a plaque) a moment when he realized, "that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers...But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun."

If you went looking for these two streets in New York-- the site of Merton's baptism and Carlin's youth--you wouldn't have to walk far to get from one to the other. They are, of course, the same block: 121st Street between Broadway and Amsterdam.

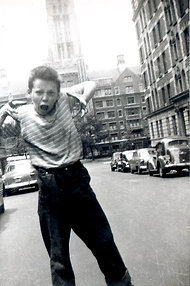

On a recent Sunday afternoon, I went walking through Morningside Heights (Carlin liked to call it "White Harlem"), in hopes of gazing upon the apartment building where Carlin was raised, the place where he stood upon the stoop at eleven years old and did his routines. I was listening to "Class Clown" on my iPod. ("If god is all powerful, can he make a rock so large that he himself can't lift it?")

As I explored the block, though, it was impossible not to be simultaneously drawn to Corpus Christi, with its lovely grey facade and its bright red door.

I walked up the stairs to find a service in progress, the air thick with the smell of incense. I sat on a pew, listening to the service, and thinking about Merton's baptism in this place on November 16, 1938, a moment he later described this way: "God...incorporated into this immense and tremendous gravitational movement which is love, which is the Holy Spirit, loved me. And He called out to me from His own immense depths."

And I thought about Carlin, who said that this same place "gave me all the tools I needed to lose my faith."

I also considered the twin journeys that I had been on myself over the last year or two, one Mertonesque, the other Carlinesque.

Sitting in Riverside Church on a January day last year, I felt something so profound and insistent that I can only describe it as a "call," something begging me to give myself over to it, and to live a life devoted to love.

Meanwhile, I'd also spent an absurd autumn on a tour bus, with Caitlyn Jenner and a group of transgender women, being filmed round the clock for a reality series on the E! network.

On the bus, I'd spent a lot of time arguing politics with Jenner and the other women. There'd been shouting and yelling, slamming doors.

We faced, on that journey, the same dilemma that now faces the country, the question of how to speak to people with whom we disagree. About half the country, more or less, cannot even have a conversation with the other half. And no matter who wins the White House in November, we'll still face this dilemma of how to regain the thing we have lost as Americans: our sense of love for one another.

I left Corpus Christi and walked down 121st Street. As I reached Morningside Drive, I looked up and saw the street sign that marks, "George Carlin Way," and thought about the ways that it was perfect poetic justice that a street named for Carlin would also be linked forever with the life of Merton.

Because just as America is not two countries, but one, so too is 121st Street one street and not two. And the key to our survival is all of us learning to listen to each other with love, and to recognize what is both carnal, and eternal, in each other.

Maybe comedy is just another form of faith: the Seven Dirty Words and the Seven Story Mountain just different ways of dwelling on one profane, immortal street. Can you tell, without googling it, which one of these men said, "Every person you look at, you can see the universe in their eyes, if you're really looking." Was it the comedian or the monk?

Are they really so different from one another? Am I really so different from you?