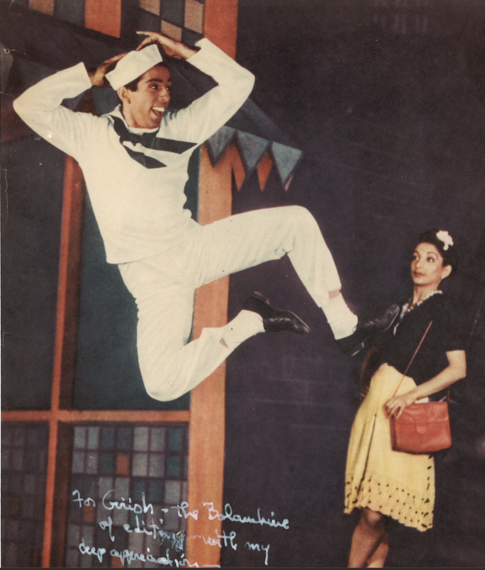

Girish Bhargava and Robert Joffrey. Photo courtesy of Girish Bhargava.

"Look at that!" Girish Bhargava shouts, his voice booming with excitement.

In a fraction of a second, Jennifer Grey goes from sneakered student to dirty dancer as a pair of heels replaces her scuffed tennies. The transition feels seamless, but it represents so much. Before, she was a timid teenager. Now, nobody is going to put Baby in a corner. She's a woman; you see it in her toes.

"I don't care about a face," Bhargava says. "I care about the feet! You don't want to cut off feet, because that's where all the work is."

He would know. For four decades, Bhargava has edited dance on film. The iconic scenes from Dirty Dancing are his doing. "Dance in America" was once his main stomping ground. He has cut choreography by some of the biggest names in the United States. Twyla Tharp is the only woman to ever have sent him flowers -- a bouquet of roses three feet long. When prompted to provide a clip for the Tony's, Jerome Robbins asked Bhargava to choose it for him. He became the go-to guy in his niche, and still is. Last fall, he and director Matthew Diamond collaborated on Ballet Hispanico's CARMEN.maquia and Club Havana for Lincoln Center at the Movies, which hit theaters in November.

"Balanchine, Robbins, Taylor, Ailey, Joffrey, Mark Morris -- he's worked on everybody's material, so he's really experienced," Diamond said. "The conversation is very, very, very high end. It's not a conversation you can have with many people, so that's fun."

Coincidentally, Bhargava never intended to edit dance. Growing up in Delhi, he wanted to be an engineer. He didn't have the venue to watch television in India, where three-hour film tragedies proved the popular form of entertainment. And he wasn't a fan of what he found onscreen, except for a 1961 musical by Robbins, who would prove one of his greatest influencers.

"I always felt with these three hours I could have done something better. I never liked that," Bhargava said. "The only movie that I enjoyed [was] West Side Story. We all came snapping out of the theater, because of Jerry."

After specializing in telecommunications at his university, the Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Bhargava spent a few months at home, where he listened to the radio every day. He fell in love with one of the female host's voices and applied to work for the local station in hopes of asking her on a date. When offered the opportunity, he left radio for an internship at the German television broadcasting company ZDF. His father -- a hunter -- sold his gun to fund the trip. Bhargava stopped in Italy on the way to Germany; starving, he searched for something to eat. He had never seen pizza or pasta, and the only food he recognized were peas. So he ate them cold for dinner, and they were terrible.

But Bhargava found his stride once he arrived in Germany. ZDF gave him a crash course in cinematography and TV production. He tried his hand at every department, gaining a basic knowledge of each peg that motivates the machine. "You could be developing film that day, or you could be recording, or you could be editing," he explained. "If I was learning in America, it would take months. Here, it was so easy."

Enticed by color television, a 26-year-old Bhargava moved to New York City with a one-way ticket. He worked for CBS, first in golf and then in news. Once, he translated a German interview for the evening report, which rolled live on air.

"It worked very well," he said. "Everything went fine. And then a couple of days later, I got a letter from Walter Cronkite thanking me for a job above and beyond the call of duty. Because I was just editing, you know? And I helped this newscast happen."

By the 1970s, Bhargava had established himself in the business. He got a call from PBS asking him to serve as chief editor for "The Great American Dream Machine," conceived and produced by Alvin H. Perlmutter. "He is without question the best editor I have ever worked with," Perlmutter said. "He's thoughtful, he's imaginative, he's efficient, and he's got a great creative streak."

Then, director Merrill Brockway approached Girish about WNET's "Dance in America," and the rest is history.

A layman in dance, Bhargava quickly developed his own sensitivity for music and motion. Brockway was a musician, and he mentored Bhargava to cut to the counts of any score. Soon, musicality was Bhargava's forte.

"I put the edit in the breath," he said. "Every time you see somebody land their foot, you can't cut it there. No, you have to wait until the foot is landed."

Most people assumed he had professional music training; how else could he have developed such an attentive ear, they wondered.

"I was working," Bhargava said, "and then Jerry said to me, 'Where do you get your musicality? You hear things -- how do you do that?' He said, 'Where did you study? Did you go to college?' And I said, 'No, it's in here. I feel it.'"

"Girish's musicality is as good as anybody's I've ever met, which is saying a lot because I've met people like Paul Taylor, and Mark Morris, and Lar Lubovitch, and Alvin Ailey. People who are remarkably musical," Diamond claimed. "In his world, he's just as musical. What exactly is that? I don't know -- it's like defining anything."

It is this musicality that gives his edits such ease. "You just know that it's his work, the way that it flows so freely, smoothly from one scene or one segment to another," Girish's wife Rosaleen Bhargava said. "All this special editing that he did, it just came natural to him. And I still don't understand why, because he's one of the worst dancers you've ever danced with. He is! He just doesn't get it."

Jodee Nimerichter, director of the American Dance Festival, seems glad that Bhargava's eye has more talent than his feet. From 1999-2002, she worked alongside him at "Dance in America" and witnessed his process.

"He is able to make a pretty miraculously perfect decision always about where a cut should go," she said. "It was fascinating to see how fast he can work, to see how he could put pieces together, to see his rationalization for why things should happen when they do happen. And he was completely concentrated and invested in what he was doing, but always very, very generous and willing to share."

"When you see a great choreographer or a great editor, you don't question what comes first, what comes second, what comes third," she continued. "It's a fluid progression of what you see onstage or on film. So when you don't have to question what's being done, it's a master."

Nimerichter was not alone in her comparison between dance and film editing. On his way to Lincoln Center, the glamorously statuesque artistic director of the New York City Ballet beamed at the mention of Girish Bhargava, pulling his hands to his heart. "He is the best in the business," Peter Martins said. "He is a choreographer and a dancer."

And with Bhargava, most agree that editing is an art, just like dance. As director Emile Ardolino wrote in 1987, at the start of his career, he had made "the assumption that videotape editors were merely technicians." After meeting Bhargava in 1974, he realized "I was working with an artist of the first rank -- one whose precision, talent, and passion have given me the gift of an ever-deepening collaboration."

You could call Bhargava a collagist. His mastery comes from the ability to take raw footage and fuse it with the music for an ideal compilation of takes. "I'll screen all the shots," he said. "I have like four hours worth of shots. And I listen to this music 10 times. And I'll say, 'Ah, I like that,' so I take that shot and stick it where it belongs. I've filled up the music with the most beautiful pictures that I like. Now the only thing left is these tiny segments, so now I'm looking for accents. Someone throwing a hand up."

Dance is an especially tricky medium to edit, as one mistake can ruin an entire shot. If a corps member turns a second too late, or the soloist falls off her pointe in a pirouette, the frame is not "very perfect," a phrase Brockway associated with Bhargava. "I will take the best take of the main dancer and somehow put it into the shot, if I can, and take the good part of the other dancers, and merge it together," Bhargava said. This is the benefit of dance on film: it allows editors and directors to clean the chaos of live performance for the most pleasing visuals.

"When you shoot from the back and you see the line, cut to the front before she goes into the arabesque," Bhargava said. "Perfect! The only thing the other angle helps is to enhance. It enhances what's coming up, not in itself, but it puts more light on what's next."

De Mille signed a photograph for Bhargava with a personal message. Photo courtesy of Girish Bhargava.

His crowning accomplishment was the closing of Agnes: The Indomitable de Mille, a 1987 documentary on the woman who gave us Rodeo. "The last scene with the fan out on the trees, it just breaks my heart every time I see it," he said. "I think that was my biggest point in my career, when I picked that shot."

It is this attention to detail, this deliberate obsession with perfection that has made choreographers feel comfortable with putting their work on tape. Dancers are often wary of offers to record their oeuvre, as few film professionals grasp how to translate dance onto the screen. "One of the problems is it's not a proscenium art, obviously, so you have to restage things like exits and entrances," said Barbara Horgan of the Balanchine Trust. "You can't just appear on the camera."

Horgan was George Balanchine's personal assistant for over 20 years and watched his frustration with dance filmography. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Balanchine was hired to choreograph for a few movies in Hollywood, where, she claimed, "he really had an education in film." Later, he recorded 14 of his ballets in Germany and was disappointed by the outcome. For decades, he didn't allow his work to be captured on tape. Then, in the 1970s, "Dance in America" convinced him to give the screen another chance.

"Balanchine more or less was thinking he wasn't ever going to do this again, and then he flew out to the editing studios. He met Girish, and obviously they spoke the same language," Horgan said. "I think Girish was impressed by the knowledge that Balanchine had of the editing process, and Balanchine was impressed by Girish, because he said Girish -- and I'm just going to use a slang word -- I think he got it. In other words, he understood right away the choreography, the musical impetus of the choreography, where the pauses were, and he wasn't adverse to having long sequences of dance."

Bhargava and Balanchine mug for the camera in allegedly the last photograph ever taken of the choreographer before his death. Photo courtesy of Girish Bhargava.

Bhargava became a favorite among choreographers for his patience and willingness to collaborate. On an especially idiosyncratic occasion, Paul Taylor sent him a handmade chandelier out of gratitude.

"When hung this here whatchamacallit can revolve and throw lights on [the] ceiling in two directions at once!!! That is, if there's a breeze," Taylor wrote in a letter. "If no breeze, which seems likely these days, try a fan. Or if that doesn't work, blow on it. Hard. Or give it a good kick."

Chandelier jokes aside, the confidence choreographers like Balanchine and Taylor shared with Bhargava prompted the dissemination and preservation of some of the most important dance works of the 20th and 21st centuries. If Bhargava is the reason we have recordings of Apollo and Company B, his contribution to dance can't be denied.

"He's been a gift to this field, a treasure now and literally for always because we are so fortunate to have these masterworks available for our viewing pleasure," Nimerichter gushed. "And he will be an inspiration forever."

Bhargava's projects function as an extensive archive for dancers, choreographers, and scholars looking to understand the history of their field.

"The combination of Merrill, and Emile, and Girish, it was so fortuitous," Horgan said. "It all came at the right time, and I think the programs are brilliant. They still stand up today. I mean, they stand up in a big way. They really capture the feeling of the company at that time, the feeling of the dancers at that time. They're classics."

Film can also inspire new audiences to celebrate dance. It can even motivate a young child to try on his first pair of ballet flats and jump into a studio. When Matthew Diamond shot Lar Lubovitch's Othello for San Francisco Ballet, he asked Desmond Richardson why he began dancing. Richardson answered that he had seen a program Diamond directed and knew he wanted to move like those performers.

"For so many people, this is the ballet, or modern dance, or Broadway show that they get to see. They can't get to New York, or they can't get to their big city, or they can't afford tickets, and yet they love it," Diamond said.

Nimerichter reciprocated Diamond's feelings about why dance on tape matters. "Television can reach mass audiences, so it is incredible when you can bring the highest level of performance into the living rooms, or bedrooms, or homes of people across the country," she said. "And you can experience what's happening in New York City -- for example, at Lincoln Center -- if you live in Iowa. It's brought right to you, and masterfully done."

For Bhargava, his ability to capture dance and share it with the American public is a source of intense pride. In Los Angeles, he lives with his wife and near his two daughters, one of whom is an Emmy Award winning producer. A wanderer from India, he has devoted his career to conveying the art of American dance onscreen. Against all odds, he's made a name for himself in television. He's created a home for himself in the dance-film world, and by doing so, he has sourced a new community for American dance.

"I always thought that America is the country where you could achieve your dreams -- where it doesn't matter what you look like, or what you are," he said. "And I feel very strongly that way. Yes, there is the American Dream. I have become it."