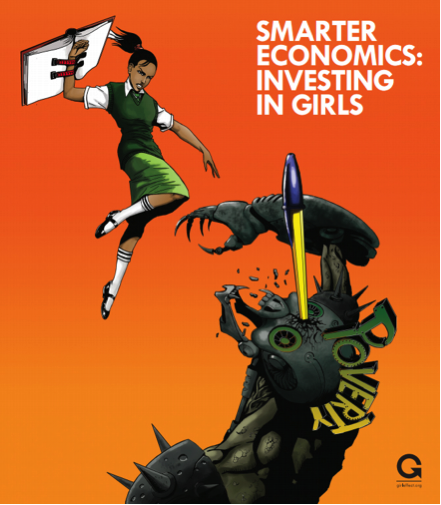

Source: Graphic from Girl Effect Report. Available here. Accessed: September 22, 2016

It is critical to analyze the narratives and visuals of development campaigns to explore what they convey beyond the frame. This includes analyzing not only the marketing/communications materials but also the languages employed by prominent advocates since they facilitate the production of a societal consensus.

Representations - textual as well as visual - are not innocuous; they are constituted by, and constitute, our ways of imagining the world, individuals, and social projects. Hence, it is crucial to ask: what kinds of knowledges about people in the global South are produced in/through development campaigns? What is highlighted and what is erased? What are the consequences of such representations for development policy and practice?

Such an interrogation is important because these ideas, which sediment over time, directly influence how we, as scholars and practitioners, engage in development policy-making and projects.

A cursory look at the textual and visual representations of dominant girls' empowerment and education campaigns, for example, highlights that this discourse is about black and brown girls from poor communities in the global South. However, these very differences of race, nation, and class are also elided.

Consider the image below. There appears to be a concerted effort to establish uniformity across differently-situated girls in the global South. Similarly, Gordon Brown, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and United Nations Special Envoy on Global Education, erases Malala's specificity by calling her "everyone's daughter."

Source here. Accessed: September 22, 2016.

Such representations allow for girls in the global South to appear as stable, knowable subjects: if we know one, we know them all. If we design a development intervention for one, we can apply it to all. If we know the hindrances for one, we can extrapolate for all.

Yet, development practitioners are deeply aware of how identity vectors - such as race, social class, urban/rural location, sexuality, religion, ability, among others - intersect to influence the opportunity set available to women and girls.

Feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw uses the term 'intersectionality' to point to the different locations and experiences of women. Writing in the context of African American women's history, she notes that the experience of a specific group of women will differ from another due to the multiplicity of identities that they embody. These analytics are significant for us to take up because hierarchies of race (and sexuality, ability, etc.) effect women's opportunities and challenges, as well as the oppressions they experience.

If we were to seriously take up intersectionality in the field of gender and development, we would begin then not with the present moment - where poverty is portrayed as a 'given' and girls as 'superheroes' who will deliver societies from it (as the above Girl Effect graphic so aptly illustrates) - but with a look into the past in order to examine how we got here.

This would lead us to explore the histories (and legacies) of colonization in the global South. There would then be no way of avoiding an analysis of the consumption patterns in the global North and how they are interconnected with the persistence of poverty in the global South. We would have to undertake a critical analysis of foreign policies and how aid is often tied to political interests.

Such an analysis would recuperate the political import of development work. It would also enable us to understand the investments and concerns that girls themselves have - an understanding which is crucial for interpreting their own narratives and representations. If we do not have a clear sense of what commitments/ challenges/ opportunities different girls have, we will undoubtedly end up reading our own concerns onto them, which might do more harm than good. Paying attention to local histories and deepening our engagement in gender and development by taking up race, sexuality, religion, nation, etc. promises better policy-making and practice.

In short, representations matter. The words and images we use in development campaigns tell a story - they amplify some ideas and erase others. It is, hence, crucial for us to be attentive to the cultural and ideological work of such campaigns. Foregrounding the analytics of intersectionality is one way in which we can ensure that we do not erase historical memory or hide the prevailing racial/sexual/religious hierarchies.

This analysis piece was presented at the Overseas Development Institute in London and posted at the LSE South Asia blog.

Dr. Shenila Khoja-Moolji is a postdoctoral scholar with the Program on Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism and the Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania. She draws on transnational feminist and postcolonial theories to write about the intersections of gender and development in the global South. Her development-related fieldwork includes projects in Afghanistan, Kenya, Pakistan, Syria, and Tajikistan. Her academic publications are available here and she tweets at @SKhojaMoolji