I've just gone to see two solo shows by two artists I've been following for several years: Melanie Vote's Images of Overgrowth at Hionas Gallery, and Nicolas Holiber's Stolen Idols at Gitler &_____. Both shows veer farther into conceptual territory than my expertise can reliably support, so I apologize in advance if I fall down a little on the job. I am writing about both shows together, despite their lack of thematic relation, because there is a striking contrast in how they were made which will emerge as we discuss them.

--

Vote's show, Images of Overgrowth, consists of an installation and several paintings. The installation is as follows:

Installation view

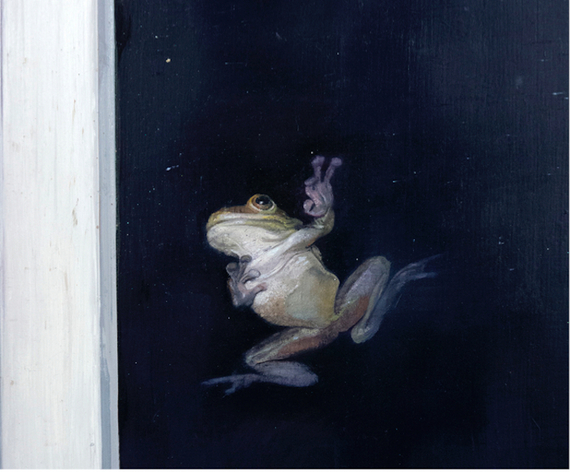

Night Visitor, (left) 2016, oil on wood, 40 x 22 x 2 in.

Growing Bed, (right) 2016, mixed media, 32 x 60 x 45 in.

As you can see, a bare room has faint regular markings on the walls - blue chalk, as it happens, which is eager to get on your shirt. Young plants erupt from a roughly person-shaped hole in a simple bed. The bed, clearly, has something to say about death, and in a serendipitous twist, the night visitor in the painted window, this theoretical bedroom's window, is a frog. Serendipitous, because for me at least, the frog in the window at night is a harbinger of death.

In another room, there is another painting, the very large Excavation of Life and Death.

Consider Vote's topic in these pieces, the installation and the painting. It is not death precisely, nor life. To be exact about it, it is the interface of the dying body with the Earth. In Growing Bed, the body prematurely dissolves into the soil and plant life which will ultimately replace it. A riot of dirt and plants trespasses on the resting place of the living, carrying the living away before its time. In Excavation of Life and Death, conversely, the archaeologist has dug down into earth undisturbed for many years, and found a human body refusing to yield to decay. The body is so complete as to seemingly retain life, to have fallen rather than died. Each piece is an unstable, even uncanny, intrusion of one element - body and Earth - into the territory of the other. They are mirror images of one another.

The final major piece in the show operates as a kind of synthesis of these opposites. A self-portrait, Place Like Home, situates Vote herself inside the borderland territory she is exploring.

Vote lies in funereal repose, a bouquet clasped in her hands. Her flesh is not corrupt, but she does not reject the plants either. Where is she lying? She is spotlit on a tiled floor, an artifact of intention and human life. And yet plants creep inward from the dark edges of the frame, usurping the role of life in this place. The place, like the pose, merges the realms of the living and the dead. Vote's eyes are closed, but she does not appear dead. Her eyebrows are lifted, so that her eyelids are only lightly closed, like the eyelids of a dreamer. She seems to be imagining herself through the phases of life and death, considering her place in many variants of the world. Therefore the painting is the world she is imagining around herself, as is the rest of the show. Of course this is true of all art, and may even define art. But this conceptual aspect of art, which always hovers in the background, moves into the foreground here, through Vote's elegant network of narrative and formal choices.

--

Moving right along, we come to Nicolas Holiber's Stolen Idols. Here is one of the odd pieces in this show:

It appears to be extraordinarily crudely made. And, indeed, it is. But there is a difference between art crudely made because of ineptitude, and art so pointedly crude, and so well conceived and executed, that it testifies to an intention smart enough to demand further thought. So, let's think.

The actual content of this piece includes the props of various classical modes of still life: cut flowers, wine and cheese, a Greco-Roman bust. These elements are contextualized in a familiar narrative as well: the bohemian studio-apartment of an artist in the city, with its cheap tablecloth, pet dog, and view of the tenement windows across the street.

And yet these elements are squashed down into a distressingly isometric space. There are no lines of perspective, because isometric representation doesn't have vanishing points. It has only a flattened plane, where every meter of edge is equal in the image to every other meter of edge. The materials from which the image is constructed are similarly offensive: sawed-up pieces of utilitarian wood planks, screws, and for color, mainly polygonal regions of flat paint.

In person, the presence of inappropriate materials is even more pronounced, as all angled views reveal the sandwich of materials which form the piece, little distinguished from a beat-up forklift pallet.

We have become accustomed to an incomplete model of the charisma of Van Gogh. He's sold as appealing on the basis of his color, his images, and his romantic biographical details. Just as important, I think, is his lack of facility. His paintings look like he's really testing the outer limits of his ability to make an image. The paint fights against him, so that it feels like a triumph that he gets it to look like anything at all. Its rebellious physicality is never far from overwhelming the ends Van Gogh bends it to. It hardly matters if this impression is true or false. The raw clumsiness of his representation, the finger-slathering thickness of his paint, makes his scenes, his themes, and his insights uniquely accessible. There is no great distance, the layman viewer feels, between his own lack of artistic skill, and that of Van Gogh. The layman thinks, "If I painted, it would probably look awkward like this." And therefore, whatever titanic insights Van Gogh may have reached, the layman feels he might reach as well. Van Gogh preaches in the common language of his congregation, giving his congregation a profound sense of ownership of the gospel.

Even so, Van Gogh uses a traditional medium of art, oil paint on a canvas. Holiber, focusing more specifically on the use of materials that do not want to make a picture, has found his medium of board and screws. There could be no more common medium; I saw a pile of it in the trash on my way back to the subway. Holiber's medium fights him every inch of the way, and its hostility never subsides. Vividly present in every piece in the show is the punk miracle of its mere being. Here, paintings of wood grain bump right up against actual wood grain:

That he is painting classical imagery suggests that he wishes to lay hands on the canon; he wants to become comfortable with the vast tradition of the West, and in so doing, pass it readily to his viewer.

--

Now we return to the reason I wrote about these two shows together, which is that they provide a striking juxtaposition of means, of the very feminine and the very masculine. To fully express their visions, Vote and Holiber find it necessary to press non-traditional media into artistic service. Their choices read almost as caricatures of gender.

Vote's concept of death does not include heaven or hell, or the void, or even much in the way of cessation. It is death-as-womb, of one thing giving up its nature to nourish the nature of the next. There is conflict at the boundary, but the drive of the show is toward reconciliation with this passage. She selects her media accordingly. Could any art be more immediately feminine than one made from growing plants? The conversion of the gallery into the garden, housing the total fusion of artistic and organic fertility?

On the other hand there is Holiber's work. His isometric projection is a system used by engineers. His media are the media of the workingman: the wood plank and the screw. He shapes them with a pencil and, I'd wager, a table saw and power drill. There is no part of his art which Holiber has not worked over to be more male. His vision is of a struggle between the heroic will of the artist and the mute antipathy of building materials.

Making art involves a filigreed procession of assertions and relinquishments of control. In the relinquishment, chaos and inspiration creep in alike, and both leave their mark on the work. Good work is lit by inspiration, and nearly as often scarred by chaos. Without the scars, as much as the light, it might readily fail to live. Vote and Holiber have, most peculiarly, found gender-specific ways to relinquish control: Vote by inviting her living materials to overwhelm her work, and Holiber by setting up an endless contest for dominion over his unconquerable media.

I have no grander conclusion to draw from this. I just thought it was interesting, and delightful, and funny. I am awfully glad that we have a Vote and a Holiber. One of the main reasons I look at art is to have interesting ideas, and this art gave me ideas I thought were interesting enough to pass along.

--

Melanie Vote, Images of Overgrowth

Hionas Gallery, 124 Forsyth Street, New York, NY 10002

until April 17th

Nicolas Holiber, Stolen Idols

Gitler &_____, 3629 Broadway, New York, NY 10031

until April 11th