I have spent four weeks trying to write a piece about race in America. Adding to an already complex and taboo topic is the alarming news about the Ferguson and Eric Garner indictment decisions. In numb disbelief, I am juggling anguish and anger while trying to keep up with the continued racism that was unfolding right before my eyes.

As is often the case after something tragic happens, we scramble to make sense of what we are thinking and feeling. Social media has served as a limitless platform for deeply stirred citizens to express and organize, displaying an American stream of consciousness that is simultaneously empowered and powerless.

You may have shared a couple articles on Facebook, retweeted some powerful quotes, or shared your own stories; please, I urge you, do not stop there. The hard part is now ahead of you - it's time to get uncomfortable.

The uprising we're witnessing in our digital and physical communities should be the impetus for engaging in some real discomfort with our friends, family, neighbors, and colleagues. To truly move forward, we have to move within ourselves to have some uncomfortable conversations about race in America.

Some people will naturally be more comfortable discussing race. Others less so. But everyone has an opinion. A good friend and mentor once explained that we all "breathe the same smog of racism," perpetuated by selective media and absorbed by all. Consider that we grow up with all types of learned biases - about the way we recycle, make lasagna, clean our apartment, and inevitably, the way we see race. After years of news consumption and fear-mongering, our underlying - and too often, unrealized - racial biases inform our behavior daily, whether we believe we have them or not.

Studies reveal that subconscious bias is pervasive. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) explained our biases in race within the context of hiring processes. David Amodio, a neuroscientist at New York University, conducted a study on implicit racial biases, revealing that "white participants might write down on a questionnaire that they are positive in their attitudes towards black people...but when you give them a behavioral measure, of how they respond to pictures of black people, compared to white people, that's when we start to see the effects come out."

Before you begin having conversations about race, a little introspection may be in order so that you can consider what racial biases you hold. For example, you may ask yourself, what thoughts come to mind when I observe a group of young black men on TV or walking past me on the street? What am I thinking when I walk through Chinatown and hear loud chatter in a foreign language? What stirs in me when I read headlines on immigration reform? What comes to mind when I receive a resume from someone by the name of "La'Trice Jackson"? Give it a week, maybe two, and observe the thoughts - and subsequent actions - that ensue. If you'd like some digital assistance, the Implicit Association Test - taken by over two million people online (myself included) - is an anonymous and trusted way to gauge your subconscious preferences.

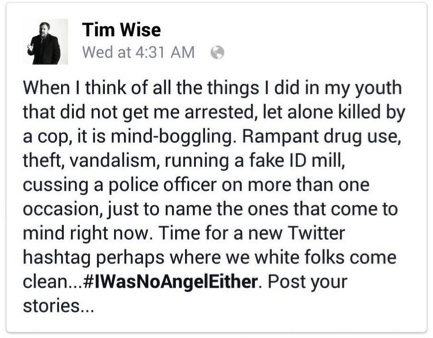

For some perspective, a number of famous and personal accounts of white privilege powerfully demonstrate a necessary acknowledgment of winners and losers in racist structures. Hashtags like #IWasNoAngelEither, #CrimingWhileWhite, and #AliveWhileBlack expose personal accounts of racialized privilege and oppression. Tim Wise, the author of Colorblind, starts with exposing his own white privilege:

For Asian Americans like me, the challenge is to awaken from the divisive nature of the "model minority" myth, arising in the 60s amidst the civil rights movement, which succeeded to pit Asian and black communities against each other. The Asian and Pacific Islander Americans (APIA) Writers' open letter of support for Mike Brown's family compellingly demonstrates why the model minority myth can and should no longer hold power against afro-Asian solidarity. Asian American civil rights activists Yuri Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs may remind us that our struggle is not so different.

I am, of course, not without my own trials and errors. A number of years ago, I was taking BART in the San Francisco Bay Area, and began to observe a bias of my own. When I stepped into a train, the decision of which open seat to take subconsciously depended on who was already seated. Without awareness, I had been biased towards taking the seats next to white and Asian people, less likely to take seats next to Black and Latino people. The observation allowed me to consider the validity of such an action. When I thought deeper, it made no difference to me whom I sat next to, so I consciously adjusted my behavior. I recall later purposely choosing to sit next to a heavyset, young, black man, greeting him as I seated. To my surprise, he actually celebrated the act and called out the rare black and Asian "solidarity" that my action silently embraced. We laughed and shook hands before he got off a few stops later.

Protestor shows off sign during a march against police brutality in Washington, DC. Photo credit: Jennifer Bryant

After you've become familiar with your own racial biases, first and foremost, accept yourself for them. Wherever you come from, whatever your background, you have been taught that those racial biases are true. The true test of your character will be how you practice unlearning them.

Civil rights attorney Morris Dees similarly prescribed, "There should be no shame that we harbor some prejudice on issues such as race...What is shameful is our failure to examine theses prejudices. "

One way to unlearn these racial biases is to turn them into conversations. (Like I said, uncomfortable conversations need to happen, but hear me out.) Only when you are aware of your own racial biases - and what triggers them - can you be open to unlearning them. Here's one trick you can try - each time you mentally arrive at a racial bias or stereotype, practice turning that thought into a question. For example, if you experience fear when passing a group of young black teenagers on the street, perhaps you may ask, "Where is my fear coming from?" "What influences in my daily life affect my perception of these teenagers?" "How does my perpetual fear of them - magnified across American society - affect their psyche?" "What is their lived experience when people constantly react to them in fear?"

The premise of these open and non-judgmental questions is that within your racial biases, there is always something deeper - an oppressive system, a family history, a tradition, or simply put, a lived experience. When you ask questions, you are allowing your mind (and heart) to expand into a deeper understanding of another human being's lived experience. This is the very nature of empathy.

Like any other charged topic, discussions of race can only be effective if guided by empathy, which is defined as "one's ability to understand and share the feelings of another." As we gear up to ask questions (and answer them), acknowledge that the person who may be sitting across from you has a unique lived experience worthy of your understanding, and truly hold space for the questions they're bravely asking, or the responses they're candidly sharing. Then try and sit with whatever discomfort arises.

It can be infuriating - and endlessly unproductive - when I open up about my racial experiences and the listener responds with justifications or explanations as to why my experiences are incorrect. Despite his or her best intentions, such a response dissuades me from sharing openly and honestly next time. As a result, dismissive or negating responses effectively build barriers and divide people.

As W. Kamau Bell puts it, "when a person of color shares a racial experience with you, acknowledge it." I would add, acknowledge, empathize, and ask another question. In other words, get comfortable with getting uncomfortable.

These uncomfortable conversations don't necessarily have to be shared with a member of the community in question. The power of asking questions at all is that it opens your mind to start considering. A good place to start might simply be with someone whom you trust, and therefore share an understanding - free of judgment - that many of us are learning to deal with being uncomfortable in how we explore real racial experiences. If you're feeling tongue tied and really unsure of where to start, then here's an easy one for you - "What do you think of Ferguson?" All you have to do is empathetically listen, and maybe ask more questions. The alternative of silence is unacceptable because it quietly perpetuates our dormant racial biases and assumptions.

Sincere curiosity behind these open and non-judgmental questions is deeply profound because it is a symbol of recognition, that a person of color has a lived experience predicated by their race. The continued practice of and commitment to empathy and trust across racial lines is the only way we will breakdown America's taboo around race and our alleged colorblindness, making way instead for our raised color-consciousness.

Join the dialogue in my blog Teng Tied.