My subject in these posts is how we look at the world. In future columns, I will be writing about all sorts of things, from hieroglyphs to ice halos, from postage stamps to insect wings. I want to gently undermine the idea that there's nothing to be said about seeing because it's easy, automatic, and natural.

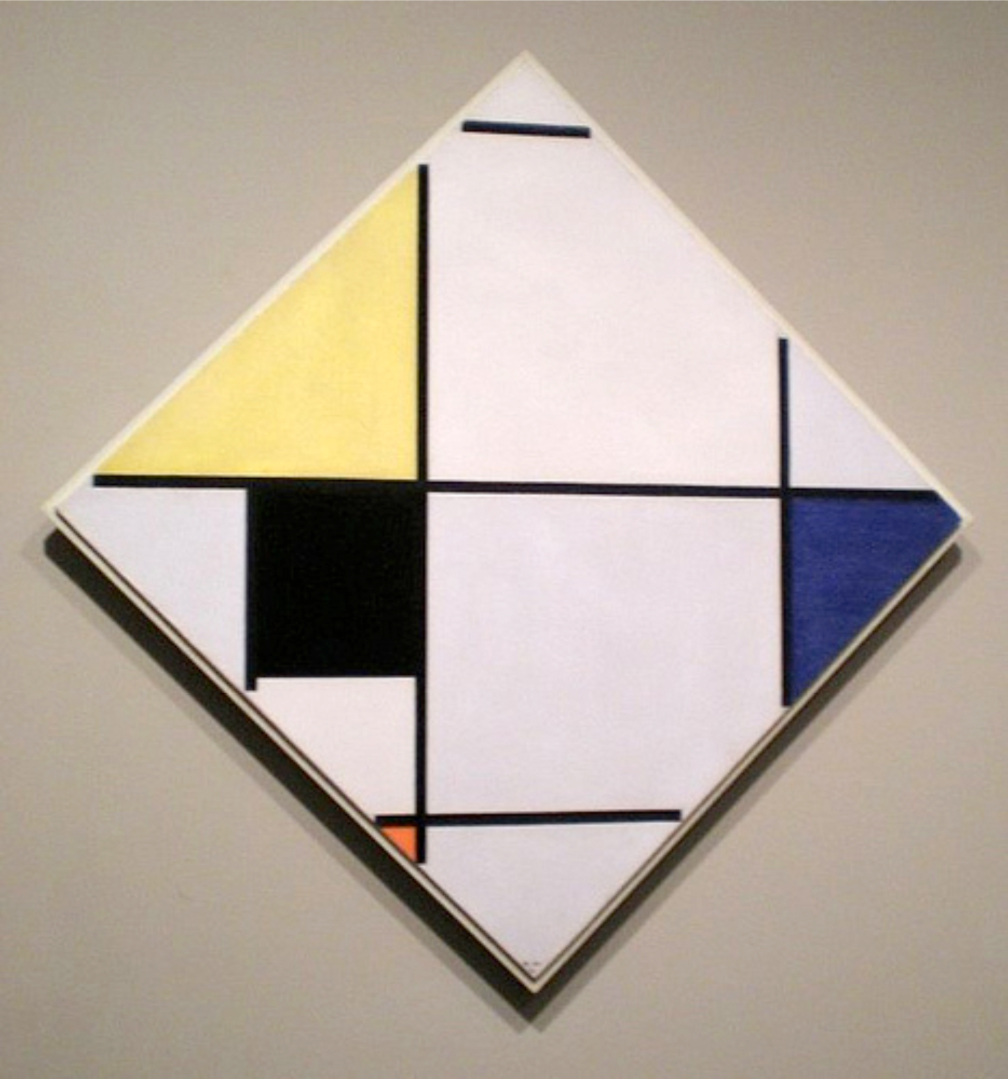

The first column in this series was about Mondrian paintings, and how closely it's possible to look at them. (Very closely, I think, even microscopically closely.) It took me more or less three years, on and off, to learn to see that Mondrian painting. If I had added up the hours I spent in front of it, and in front of my computer looking at JPEGs of it, it would probably be about 100 hours, or about 2 weeks of looking, 40 hours a week.

That is a lot, but it's nothing compared with some people. When I taught classes in the Art Institute in Chicago, I ran into people who came to the museum regularly, over a period of years.

Rembrandt (school), Young Woman at an Open Half-Door

An elderly woman told she came to see one of the Art Institute's Rembrandt paintings -- a curious picture of a young woman, leaning on the bottom half of a Dutch door -- three or four times a week during her lunch hour. How long had she done that? I asked. She said, "I don't know. Decades." To be conservative, let's say she meant two decades, and let's say her lunch hour was one hour. That's 3,000 hours of looking. If looking had been her 9 to 5 job, that's over a year of doing nothing but sitting in front of one painting. What amazing conversations she must have had with the woman in that painting!

There's a book by the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard, called Old Masters, in which a man goes to see a painting in the museum in Vienna every other day for his entire adult life. He does that for an entirely different reason than the woman in Chicago: he goes because he's so desperately misanthropic that he hates everything and everyone, except this one painting -- a painting by Tintoretto -- which he sort of likes. It is an unidentified portrait, so no story goes with it, only a face. He goes and sits in front of it and ponders how much he dislikes everything except that one man's face.

Either way, hate or love, to spend that much time in front of an artwork, you have to be in dialogue with it. You have to listen to it, and think something in response, and look again, and see how the work has changed. You have to believe that you can have an ongoing, evolving relationship with something that is unchanging. Many people might say that is impossible.

Looking for a long time is not the usual way people see artworks. The usual interaction with an artwork is a glance or a glimpse or a cursory look. What I have in mind is a different kind of experience: not just glancing, but looking, staring, gazing, sitting or standing transfixed: forgetting, temporarily, the errands you have to run, or the meeting you're late for, and thinking, living, only inside the work. Falling in love with an artwork, finding that you somehow need it, wanting to return to it, wanting to keep it in your life.

I would like to hear from anyone who has an experience like this, and from anyone who has spent a long time looking at an artwork. What happens after the first few minutes? Why do you want to return?

There have been a number of surveys of how visitors interact with paintings in museums. One found that an average viewer goes up to a painting, looks at it for less than two seconds, reads the wall text for another 10 seconds, glances at the painting to verify something in the text, and moves on. Another survey concluded people looked for a median time of 17 seconds. The Louvre found that people looked at the Mona Lisa an average of 15 seconds, which makes you wonder how long they spend on the other 35,000 works in the collection. A survey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art supposedly found that people look at artworks for an average of 32.5 seconds each, but they must not have counted the ones people glance at.

The Internet has many entertaining pictures of people looking, or not looking, at paintings. This one is captioned "That man is not looking at a painting."

Photo by Ann Althouse

All this goes to show that our encounters are usually brief encounters or non-encounters. But this is not a simple topic: a momentary glimpse of someone, as we all know from ordinary life, can be intense, and it can seem to last an entire lifetime.

To open this conversation, I will describe a painting that was meant to be looked at for a long time, and I'll try, in the space of a few paragraphs, to conjure the way it might have felt to look at it for hours on end, day after day.

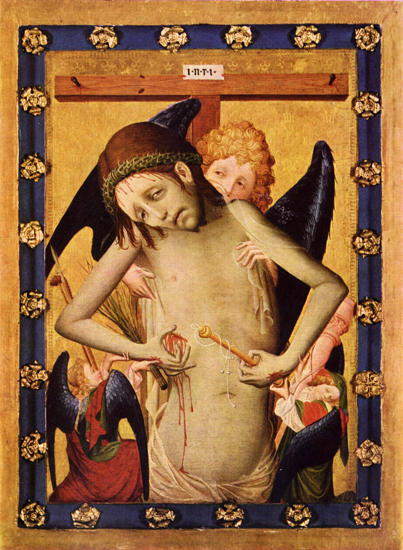

Toward the end of the middle ages, in the fourteenth century, a new kind of painting came into being that was specifically intended to produce an intense, emotional experience. Instead of showing Christ or the Virgin in full-length poses, the new pictures brought them forward and depicted them in half-length, from the waist up. That way the holy figures were nearer the beholder: as one art historian says, they evoked "the immediacy of a quiet conversation."

The painters experimented with "close-ups" of commonly painted stories. For example, instead of painting the whole scene of the Flagellation of Christ, with Jesus bound to a column, being whipped by Roman soldiers with Pontius Pilate looking on, they would paint Jesus alone, His wounds bleeding, looking straight out of the picture at us. (This is an example in Leipzig.)

The new painters made double portraits, connected by a hinge. On one side they put Jesus as the Man of Sorrows with his scourge and crown of thorns, and on the other the Virgin, weeping. The double pictures opened like books, so viewers could stand them up on a table or a home altar. Mary would seem to be looking across the hinge at Jesus.

I can imagine sitting with such a double portrait open in front of me: it would be as if I had joined a quiet group of mourners, sitting in a close circle. If I spoke, it would be in a whisper. I would be in intimate conversation, hemmed in by the suffering Savior and the stricken Madonna.

The closely cropped half-length portraits, sometimes called "devotional images" (in German, Andachtsbilder) must have moved many people to tears. There was a new doctrine in the air, enjoining worshippers to do more than just sympathize with Jesus or Mary: the aim of prayer was to identify with them bodily, to try to think of yourself as Jesus, or as the Mother of God. You would look at such an image steadily, sometimes for hours or days on end, burrowing deeper and deeper into the mind of the Savior or the Virgin. Finally you would come to feel what they had felt, and you would see the world, at least in some small part, through their eyes. At that point their tears would be your tears. In the medieval doctrine, you would be crying "compunctive" tears: God's tears at our sins, given back to God.

Across the street from where I work, we have a lovely example of an Andachtsbild, Dieric Bouts's Weeping Madonna. It was a popular composition, and Bouts had his workshop do several versions. They are small paintings, the size that would have fit well on a shelf.

The painting in Chicago is gorgeous, one of the finest of its kind. The Virgin Mary sits in a room, alone. Her cloak is lopsided, pulled up carelessly over her head. She is not shaking or wailing, as she is in other paintings: instead she is praying quietly. There was once a hinge connecting this to a facing painting of Jesus. The Metropolitan Museum in New York has a later version, with both sides intact. (The Met's is more roughly painted, and not as moving as the one in Chicago.)

In the Chicago painting, the Madonna faces in Jesus's direction, but doesn't look at him. Her hands are pressed together gently and firmly, the fingers of one hand resting in the depressions between the fingers of the other. Her little fingers are held apart from the others, and slightly bent. The pads of the fingers push a little against one another. They are interesting hands: careless and yet tense, spontaneous but fixed in place.

Her face has the same deliberation. Her lips are pressed closed, but her teeth are not clenched. The corner of her mouth has that slight indentation that is an infallible sign of tension -- the gentlest echo of the deep groove that forms when the mouth opens in grief. Her mouth is set, but not too hard. The slight unmistakable tenseness in the mouth and fingers is a wonderful touch: it stands for her fragile composure, her resolution.

Her hands and her mouth are enough to tell the story, but the painting is really about her eyes. They are masterpieces of modulated expression. Her left eye (the one farther from us) is extremely sad; it turns away from us, and away from Jesus, into the dark folds of her veil. The nearer eye, if you look at it alone, seems to look back at you with an unsettling abstracted glance. Together, her two eyes give us a face that is just barely focused on its object. We are meant to know that Jesus is dead, and the Madonna's thoughts are turning inward. Her eyes have almost lost their grip on what they see. They only stay focused because of her continuing effort. In the moments before the one depicted in the painting, she must have been wild-eyed, wailing and crying hard. Now the initial burst of passion has ebbed, and her tears have dwindled to a steady succession of drops. Her eyelids are puffed from crying, and both eyes are red. The capillaries in her corneas are swollen, coloring her eyes a deep pink. Tears are dripping slowly down her cheeks. The further eye has two drops, and a third down on the cheek. The near eye is overflowing with tears -- you can see the brim, lucent on the lower lid. One tear has formed toward the back of the eye, and another is just dropping from the front. Two tears have fallen ahead of them: one on her cheek, and another that is about to swerve and run into her mouth.

The sadness of this is the way her grief is measured out. She only cried out loud when Jesus was put on the cross, and then brought down and buried. But in Bouts's version she will never stop crying, as long as she lives. For years, she will have the same half-absent look, the same taut expression. Her tears now are everyday tears. The crucifixion could have happened years ago, for all we know: this is a painting about a state of mind, a permanent low-level mourning. What she feels is consonant with Christian doctrine: the Madonna knew what would happen before Jesus was grown, and she still has that knowledge. It is a kind of eternal sadness, which will not be dulled by time. She remains in her room, weeping. Her slightly unfocused eye will always see the death of her Son.

I have written about this image at more length elsewhere. Here I have just said enough, I hope, to suggest how a person might spend hours, and in the end years, in private communion with the figure in this painting. How long does it take to see this painting? A lifetime, more or less.

Christian meanings have ebbed from serious art, but that does not mean we have lost reasons to see artworks slowly, with care and attention. Time, patience, immersion: these are qualities that some art continues to call for, whether or not it is Christian. I'm sorry I lost touch with that woman in the Art Institute who looked at the Rembrandt. I wonder, in the end, what it told her, and what she said to it.