The backstory leading up to the jaw-droppingly beautiful exhibition of new paintings by Stanley Casselman at Brintz Galleries in Palm Beach presents fascinating and engaging clues from the evolutionary road that the artist has traveled since his attraction to manipulating clay as a college student at Pitzer in Claremont, California. The artist's "Red Sea parting" moment came while majoring in economics, through the advice of his ceramics professor, David Furman, who persuaded Casselman that he had the natural ability and insight to become a painter and that he should take a painting class. It's a story that has many interesting parallels to those of hugely successful artists like Dale Chihuly, who started out as a textile major, which eventually led him to weaving glass together,and later, creatively expanding molten glass into translucent sculpture; or the billboard painter James Rosenquist, who carried his sometimes dangerous professional experiences from a one-man balancing act on scaffolding high in the air into his downtown Manhattan studio to become a stalwart of Pop Art by appropriating advertising pictures into his compositions. Likewise, Andy Warhol, whose exclusive source material also was borrowed imagery, parlayed his childhood fascination with movie stars into controversial silkscreen paintings that were created by pulling a squeegee across a blank canvas. It also needs to be noted that Roy Lichtenstein first worked as a commercial artist and window dresser, where he cultivated a fascination with cartoons and everyday objects that he captured in his artwork by an idiosyncratic abstraction painted through stencils, and for a time closely resembled Warhol's early paintings. Resemblances in styles and influences then and now are an acceptable and frequently celebrated reality in picture-making, where artists deliberately overlap with each other, often inseparably like the early experimental Cubist works of Picasso and Braque, which for years were identical as they continued to break down compositional conventions, and preceded the ultimate reuse of the printed page with the invention of collage. At some point, however, they went their separate ways.

In Casselman's case, the familiarity with textures, coupled with the thick, tactile, earthy nature of clay that he manipulated with rubber and metal-edged "ribs," naturally and eventually carried over to his unique approach to painting, which he has been exploring for over twenty-five years. While in college, he used those ribs, essentially mini-squeegees, to define, mold or uncover hidden layers -- techniques that he continues to use on a much bigger scale today, as he methodically spreads paint across a tightly-stretched canvas. Through years of trial and error and always with his myriad of custom-built squeegees, Stanley Casselman has carefully crafted his personal iconic surfaces that began to get results and draw critical attention.

Then, as luck would have it, after a work by Gerhard Richter sold at auction for a staggering $34.2 million, along came a challenge on Facebook proposed by Jerry Saltz, eminent art critic for New York magazine, which challenged artists to produce a painting in a perfect Richteresque-style for just $155, and Saltz would come for a studio visit. The thought of having one of Manhattan's most important critics visit Casselman's studio seemed too good for him to pass up, yet he was quite conflicted about the idea of copying Richter, or anyone, for that matter. However, caution to the wind, he set out to decode Richter's language. Encouraged by the ongoing explosive experiments and the promising results in his studio, Casselman knew he had something and indeed he succeeded. Saltz visited and got his painting; $155 changed hands; but Jerry was so taken by what Casselman had created that he decided to write a feature story about it in New York magazine.

Stanley Casselman working in his studio.

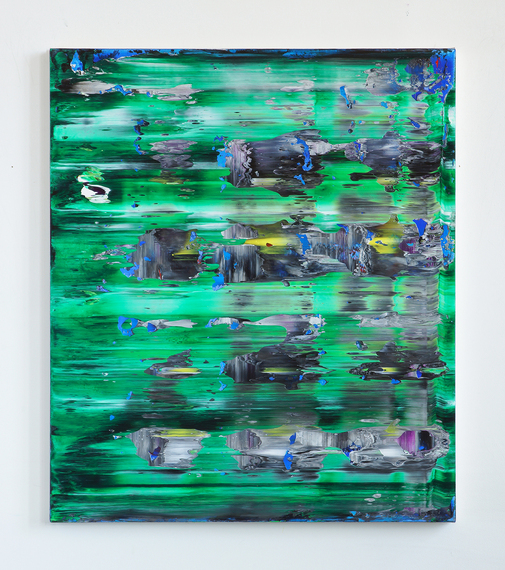

The best part of this historic tale is that in Casselman's paintings -- what led him here aside -- he's created a novel syntax that doesn't exist in Richter's repertoire. His recent small and large-scale works have been well received and seem to go well beyond Richter's standard fare. In addition, Casselman has perfected a delightful surface consisting of the unique practice of meticulously applying thick and thin paint, then pulling a squeegee across the canvas surface both vertically and horizontally, resulting in brilliant colors flowing and merging together to form a cohesive visual statement. Casselman, like an architect, plans well ahead to construct a strong, painterly foundation, which allows him to explore an adventuresome journey that ultimately provides structure, density, layering, fluidity, harmonic movement, spatial illusion and rich texture with a propensity for producing truly powerful works of art.

I'm reminded of the remarkable similarities between Casselman's background and serendipitous "luck of the draw" and that of acclaimed artist Harold Shapinsky, whose "discovery" was the subject of a lengthy feature article in The New Yorker in 1985. Shapinsky was a young man when he began painting abstract expressionist-based works in total obscurity, which he continued refining every day for over thirty years before he was noticed by accident. He had studied briefly with de Kooning and Motherwell, and then he diligently built a hybrid style that was associated closely with de Kooning's; in fact, Shapinsky's work often was misinterpreted as that of de Kooning. But curators and critics, including Kenworth Moffett, former director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, argued that Shapinsky perhaps was more original, and questioned "who came first?" His first exhibition in America was at my Palm Beach gallery, which nearly sold out, and included a painting that was purchased by Henry Ford. Next for Shapinsky was an acquisition by the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., and other museums, and finally an auction at Sotheby's, with the final sale amount ten times that of the original gallery price.

In a way, Casselman was indirectly "discovered" when he took on a challenge that coincidentally pushed him forward and into the spotlight. Like Shapinsky, he was influenced by a universally recognized artist, but also like Shapinsky, he developed an engaging style of his own making through painstaking investigation that is now paying off both critically and financially. Museums are beginning to collect his work; shows are selling out in New York, California and London; reviews are coming in from The New York Times, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal and New York magazine; as well as a recent Phillips auction with one of his works bringing a stellar price. It's a pretty astonishing connection between these two artists.

Even without the amazing backstory or the arm's-length attachments; appropriations aside, and with subtle coincidences and other obscure references to Rothko, Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, and others; these works offer a remarkable singularity of character, resourcefulness and a confidence of spirit that is refreshing, stimulating and striking all at once. Casselman offers an impressive, revealing visual parallel to a geologist's study of the layers of the earth's surface as moved by a force of nature or gravity, full of revelation and knowledge.

Stanley Casselman, The Physics of Surface Tension, through April 12, 2015. Brintz Galleries, 375 South County Road, Palm Beach, FL 33480 http://brintzgalleries.com/