Twyla Tharp's 50th Anniversary Tour may have completed its 17-city tour of the US this November, but the images that Tharp imparted through her dances have the lingering resonance of great art. Such a resonance is only in part the effect of the bitter irony that the dances Tharp premiered both grew out of the 9/11 terror in New York and were finally relayed to New York audiences just as the maniacal Islamic State taunted New Yorkers with a video threatening another attack on the city equal to that unleashed on Paris a week earlier. Even had the irony of such terroristic confluences not convened during her New York premiere, Tharp's anniversary dances would just as likely stand out in the history of modern dance for offering their audience two opposing if historically-conjoined images and sensibilities to consider as responses to terror, and in the larger sense to the experience and conceptualization of Order and Chaos as the unremitting forces to which all things must submit.

Of course artists are always to some degree responsive to and representative of order and chaos. In giving form and idea to raw materials and actions and bringing such productions into a social context, order is enacted. Or in making art that provokes outrage and protest, especially in deconstructing or deforming objects, traditions, or beliefs, an artist instills a chaos of the mind and culture, or at least a disorder of emotions and materials. In short, the artist when effective, compels us to consider whether order and chaos exist separately or must occupy the mind simultaneously by each necessitating its apparent opposite. It is also generally artists who personify order and chaos as gods among the world's tribes and civilizations, and with considerable and lasting global symbolism in the case of the Greek and Indian gods pictured and discussed here.

Tharp informs us that the dances she premiered in 2015 are the long-awaited and complexly-layered culmination to a cathartic process she devised to cope with the devastation that came with the airplanes crashing into the World Trade Center towers and the rain of death they poured down upon the outdoor plaza below where just three days earlier Tharp's dance company had performed the final performance in a summer series of free theater. Naturally the incomprehensibility of so utter and complete an annihilation wrecked on such a great cultural symbol is magnified for those who have been in close physical and temporal proximity to them. In the program notes for the premier written by Robert Johnson, Tharp's catharsis during and after the World Trade Center destruction is detailed.

"Back in 2001 ... the horror of the terrorist attacks left [Tharp] reeling, but reaching for balance and thinking of the initials WTC she found a compact-disc recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier. Bach's compendium of matched preludes and fugues for keyboard spark with brilliance, and recall the reassuring discipline of a musician's (or a dancer's) daily practice. For Tharp, these beautiful, sanity-saving exercises also embody diversity. As pianists move from one prelude and fugue to the next, they visit all 24 major and minor keys, traveling around the so-called 'circle of fifths,' a diagram that illustrates pitch relationships. Within this orderly progression, limitless variations are possible; and Bach demonstrates his versatility by composing pieces of varying length and by adopting different styles."

Bach's discipline helped Tharp attain the sanity required to endure the despair ensuing the chaos of 9/11. To have made the dances in any way disruptive of the Protestant ethic of securing order embodied by Bach would have defeated and maligned the ethos of the project. But then came the next and oppositional suite of dances that not only compensated for the intent sobriety of Preludes and Fugues, in its staging of a modern bacchanalia, it purposefully overcompensated for it with theatrical and romanticized, if not primitivist relish.

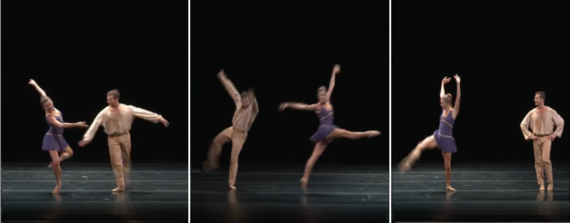

Tharp like every professional dancer or athlete knows that not a day can go by without maintaining the discipline required by the body to stave off its gradual relaxation into lethargy. Perhaps such Type-A individuals also know better than anyone else how near at hand the impulse is to collapse into a hedonism of escapes, erotic gratifications and intoxications. Such a discipline in a nation founded on the Protestant work ethic may seem hardly out of the ordinary, but in counterpointing it forcefully with its opposing cultural archetype as Tharp has done in her suite of dances entitled Yowzie, is to give what today is a rare and prolonged look at what awaits our surrender to not just hedonistic pleasure, but to the addictive, lascivious and even criminalistic lures that moralists fear will proceed from too much pleasure. With such conventional misgivings obviously in mind, Tharp had initially paired the two dances -- the one illustrative of order, the other of disorder and ultimately chaos -- as the binary outcomes of her search for a coping mechanism to alleviate her own distress. But from this simple idea of there being two opposite and polarizing tendencies for survival in life come such starkly different and extreme responses to adversity. In realizing this Tharp went on to compose a contrasting morality tale of sorts, though one in tune with the sociology of a society open to great diversity. Nontheless, the binary opposition that Tharp has devised for our entertainment settles at the two poles of modern society: the one aimed at social achievements, the other aimed at the pursuit of pleasure.

Thankfully Tharp has the grace of mind and talent to depict the follies of humankind with comic self-deprecation. For we are, after all, watching ourselves, or what could be ourselves given one little push up or down the latter of privilege and fortune. It is this intimacy between discipline and hedonism, whether in the wake of the ongoing terror threats and strikes reported around the world or during a relatively calm period of global rapport and stability, that make us acutely aware of the corresponding intimacy between order and chaos, and the more predominant middle zone of normalcy in our lives. Tharp did not at the outset chose the ever present contest between order and chaos to be the impetus for her choreography. That was something forced on her, and she responded to that force by making dances that show the range of human response to adversity in the effort to regain a sense of normalcy.

Normalcy it turns out is the ever present struggle of all species to maintain order despite the chaos that intervenes. As such, the degrees of discipline and its relaxation became both her topic and her modus operandi for the dancers as she choreographed two diametrically opposed suites of dances: Preludes and Fugues, which portrays the optimistic and athletic proponents of order like herself, and Yowzie, which sketches out the hedonistic, debauched, even the criminal submission to chaos that envelopes those individuals and groups more inclined to hedonism and orgiastic gratifications. Perhaps they are all despairing survivors, a refugee subculture leveled by wars that have been heaped on them by superpowers composed by the kind of privileged individuals we see in Preludes and Fugues and who appear unconcerned with such misfortunes as annihilation, impoverishment and the militarization of society. In this picture the difference between the populations of Preludes and Fugues and Yowzie serve as a morality tale about the differences, say, between affluent societies and the societies that get exploited by them.

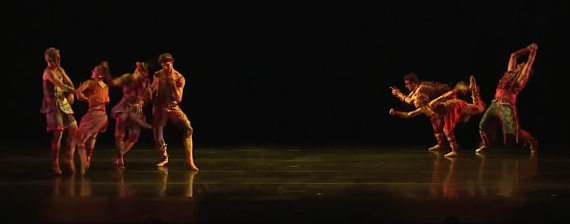

Posed in distinct opposition to the structure and discipline of Preludes and Fugues, Yowzie courts audience associations both pleasurable and torturous as we watch the dancers collapse and collide in fits and bursts of sometimes driven and sometimes exhaustive and demeaning hedonistic self-gratifications -- an illusion that every dancer knows in fact requires even more discipline than the dance displaying its discipline openly. Throughout the short collection of dances, Tharp's dancers act out something more than dance movement -- ordinary if exaggerated expressions, defensive attitudes, sociological and psychological cliches of dependence, domination, incompatibility. Also coming into play are the overly familiar semiotics of film, TV, the web and reality, all converging with the impression of reality mimicking its own dramatizations and comedies. I personally have interpreted seeing abductions, shakedowns, muggings, rape, shootouts, rescues, emergency support, threesomes, foursomes, orgies, men leaving women for men, women with women, women lifting men, women lifting women. It is the totality of these theatrical signs in conjunction with the feigned relaxation of technical finesse by the dancers that together imparts the vaudeville-like amorality to which we recount the dire warnings of arch evangelists to not succumb to the lewdness and intoxications the we know not just from life, but from an altogether more sympathetic history of art. In fact, by all appearances, Tharp defers to the archives of artistic and literary history conveying the legendary delights and entrapments of the mythological bacchanalia displayed throughout this page.

How does such a stark polarization of human temperaments respond to the tragedy of 9/11? Tharp explains that "the two pieces are at extremes of the spectrum." While the dance set to Bach affirms the artist's trust "in the power art has to substitute order for chaos", the two dances together reflect the philosopher's most elementary lesson on the difference between, in Tharp's words, "the way the world should be," and "the way the world is." Two brief fanfares with music by John Zorn precede the two larger suites, which Tharp professes consider both options equallly.

Apollonian vs. Dionysian or Sublimation vs. Desublimation

Of course Tharp is perpetuating the millennia-old contest that has been named for its most renown idealizations in ancient Greek and Roman art and myth. As it turns out, it is from the Greek dichotomy in dance that became famously known as the Apollonian and the Dionysian asthetics. Over the centuries the ancient Greeks polarized the two tendencies in art and drama. Apollonian dance, we are told, was ceremonial and austere, strictly choreographed according to formal patterns and prescribed movements. They were institutionalized and thereby commemorative of power and authority, upheld tradition and esteemed order and beauty as highly intellectualized and formal qualities bestowed by the gods, especially Apollo, the god of the Sun, and thereby of order in the cosmos.

Dionysian dance, also known by its Roman name, Bacchanalia, embodied the polar opposite of everything the Apollonian dances aspired to. Passionate and improvised according to the whims of the dancer, they were the dances that the ritual intoxicants broke into to symbolize their defiance of moral and political authorities and their trust in and love of the self. At the peak of their popularity, Dionysian dances were orgiastic and accompanied the art of intoxication in worshipful devotion to Dionysius the god of wine, dreams and wanton sexuality. Female followers inspired the myth of the maenads (or bacchae to the Romans) whose ritual intoxication produced such wild abandon as to hunt and kill wild forest and mountain animals with their bare hands while drinking their blood.

And yet only the arts could be thought to appease both the gods, and with both made patrons of the arts, but of dance in particular -- all of which ensured both Apollo and Dionysius were favorite subjects of artists up to the modern era.

By all appearances, Tharp is more inclined toward the Apollonian dance, a predilection betrayed by Tharp's compromise made in the degree to which she will consent to indulging the lewder debasements of the Dionysian disorder without showing us the negative tendencies of the Apollonian disposition that include the militarization of nations, even the authoritarianism of dictators who impose their ideal of social order.To be fair to Tharp, however, in tapping the improvisational and now traditional sensibilities of jazz immortalized by Thomas "Fats" Waller, Jelly Roll Morton and Henry Butler rather than selecting the anarchic sensibilities of, say, The Clash, indicates the degree to which Tharp compromises the true abandonment of refinement and restraint required to portray the debauchery and intoxication of Dionysian self-obliteration.

While all this concern with Apllonian and Dionysian sensibilities is the romanticist's terminology based on an archaic model, a more current psychological and sociological phrasing of this dichotomy of human behaviors came to be applied to society at the beginning of the 20th century with Sigmund Freud's dialectic of Sublimation and Desublimation. Here it is the unconscious yet socially-enforced systems of rewards imposed upon an individual from childhood on that takes charge of the moral person's education through sublimation, a process ensuring we all undergo a conversion away from what Freud calls the infantile Pleasure Principle. What the Greeks and what Nietzsche described as the Apollonian order, Freud called the sublimation of socially proscribed behaviors and desires, the kind that impetus for governments, economies and technologies capable today producing such achievements as space flight and moon walks. For Tharp, the sublimated principle governs The Well-Tempered Clavier that is the musical accompaniment to her dance Preludes and Fugues. Of course, as stated earlier but bares regular repeating, the Apollonian discipline is also required by the higher social order and the institutions of powerful governments, including those maintained by authoritarian regimes.

That Tharp doesn't end with Bach, that she reaches for the arousing jazz of Morton and Waller for her suite, Yowzie, on the other hand, indicates she hears the clarion wisdom of Ecclesiastes "to every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven". In this case the season calls for the Pleasure Principle of Freud, or what the political philosopher Herbert Marcuse re-conceptualized in post-Freudian terms as Desublimation, the hedonistic breakdown of discipline and moral principles in the primacy of pleasure enabled by affluent societies and that dramatically and tumultuously characterized the dissent forced upon Western society by the youth and counterculture of the 1960s -- Tharp's generational and cultural alma mater of the street.

But it's not for all these academic terminologies and principles that we might wish to appraise Tharp's 50th Anniversary dances in terms of the dialectical processes of the Apollonian-Dionysian or the Sublimation-Desublimation of human drives. Such terms and categories are useful to helps us recall and locate the art of history that Tharp's dances emulate if not grow from, as much as they impacted on the educated yet rebellious youth of the 1960s and 1970s, the decades in which Tharp began her choreographic career and whose music (The Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, Frank Sinatra, Billy Joel) still accompanies and informs her dances. It is also in the 1960s that culture began widening its influences to assimilate the arts and philosophies of non-Western cultures required to better understand and ease global tensions while eradicating the superstitions and bigotries that underly militarization and terror.

Yet Tharp's misgivings about cutting to the bone of dance to portray the darkest side of the human psyche reveal her mainstream aspirations, just as her resistance to staging tragedies makes apparent her deferral to the current taste for irony among intellectual audiences inclined to find tragedy too overwrought with gratuitous self-indulgence meant to seem imposed by Nature while it in fact betrays the human conceits that devolve too easily into melodrama.

We should expect nothing less from Tharp, given that long before she indulged Hollywood and Broadway, she learned from such temperate and serene Apollonian masters as Merce Cunningham and his partner the composer John Cage -- artists who reduced dance and music to their bare and abstract constituents. As an artist in her own rite, Tharp's introduction to audiences was as a member of the New York avant-garde of minimalist dancers that in the 1960s grew out of the Judson Dance Theater, a milieu of visual artists, dancers, filmmakers, poets and musicians who came together for a decade and a half. With many of them born during World War II and grown up with the specter of nuclear holocaust and a fashionable Existenialist zeitgeist critique of civilization that categorized Aushwitz, Hiroshima, the Gulags and the Cultural Revolution of Beijing as proof that all the great art of history and all its Apollonian splendor could not purge its civilization of the barbarian lust for chaos.

The supremely Apollonian aesthetic of Minimalism in art, music and dance became a kind of puritanism holding back artists, the young Tharp included, from employing gratuitous entertainments and tropes. Such puritanism was nowhere better expressed than in the famous 1965 "No Manifesto" issued by the leading Minimalist Judson dancer and choreographer, Yvonne Rainer. Rainer's spare approach to dance grew as much out of the political theory of another great Apollonian, the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, whose distancing effect in theater came to inform the reductionist dictates of Minimalist dance. Rainer's intent was to eliminate any and all elements in her staged performances (and later her films) that might lead to frivolous entertainments. Her method of negation said: "No to spectacle. No to virtuosity. No to transformations and magic and make-believe. No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image. No to the heroic. No to the anti-heroic. No to trash imagery. No to involvement of performer or spectator. No to style. No to camp. No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer. No to eccentricity. No to moving or being moved."

Those nostalgic for the days when artists, poets, filmmakers and dancers collaborated on dance might say that Tharp devolved from the avant-garde, others that she transcended it. In either case she proved she was the modern choreographer best equipped to assimilate into a more vernacular, audience-friendly choreography. Yet Tharp to this day retains the lessons she learned during the mid-20th century crises of modern art and dance theory exercised by the advocates of Existentialism, Pop Art, Minimalism and Structuralism, all of whom sought to strip the arts of all their ostentatious trappings and tropes. Yet even today something of this erudite puritanism and frailty limits the current state of dramatic theater, especially regarding the tragedy.

Tharp, for instance, might have staged a dance about tragedy after 9/11. Perhaps the paucity of tragedies produced by dance companies today indicates why she didn't. Tragedies seem to have become unpopular among dance audiences. One might be hard pressed to recall a modern choreographer after Martha Graham who famously achieved the balance required to make dances about tragic circumstances which have sustaining appeal. With cinema and video and the emphasis on the close up dominating the mediation of the dramatic repertoire to the extent of defining what is and isn't effective theater today, the former grand gesture even onstage, and especially scenes of lamentation, are received with discomfort, even derision, by contemporary audiences. We have become accustomed to directors and actors resorting to more subtle and self-conscious reflections of tragic events rather than the open grief that once held audiences rapt but now comes off overwrought, even deadening, as opposed to the privileged glimpse at virtue it was formerly -- and that is throughout history -- regarded. Tharp has always shown herself to be acutely aware of what contemporary audiences for dance will favor, let alone tolerate, regardless of what walks of life they have followed to the theater.

But all that is the Apollonian view, the shift that modernism despite all its expressionist angst seems to support most emphatically. The truly Dionysian choreographer unleashed would by today's standards appear distraught when attempting to portray terror in dance. By contrast the impotence that is felt in the face of terror lends itself to contemporary dance exceptionally, as Tharp shows us in Yowzie, because it is signaled entirely by underwhelming gestures and movements that suggest a persona that has become stunted or lost to oblivion, or by over-the-top comic gestures that read as knowingly and winningly self-deprecating.

The remarkable ease with which we can find Tharp's dances correlating the vernacular body language of today and the formulaic semiotics of cinema, television and the web to the greater legacy of art, philosophical and literary history conveys how profoundly rooted Tharp's art is in the cultural, spiritual, and social rituals that are as much the universal root to modern ideologies and cultures as they are the required components of history. Tharp surely has looked to history when composing her version of the bacchanalia that is Yowzie. Yet even when Tharp humorously correlates the vernacular visual languages of popular culture into a vaudevillian cabaret act of the Jazz Age or a 21-century rendition of HAIR, as she did for the Milos Film in 1979 and does again in Yowzie, she retains a correspondence to the origins of such vernaculars in the anthropomorphic accounts of the world's mysterious physical forces as myths that have somehow shaped, yet really summarized the universe.

In this regard Tharp's reveler's are more than the protagonists of the Roaring Twenties and the Swinging Sixties they take their cues from. Like the patchwork costumes that her dancers wear throughout Yowzie, they are a pastiche of the troubled rebels of the millennia, extending back to a neolithic, even a paleolithic time in which intoxication was honored as shamanistic entry to a spirit world whereby dance was a vehicle for communion with powerful entities, animals and otherworldly experiences. In this regard, it is enlightening to set the dances of Tharp's 50th Anniversary tour against the backdrop of a long line of art historical iconography informing the opposing principles of Apollonian and Dionysian art respectively at work in Tharp's Preludes and Fugues and Yowzie. Like all great artists, Tharp reaches across cultures and epochs with an eye for the most universally relevant signage to have impacted civilizations, even when she may not always remember or be fully aware of them. It is against this historical backdrop that Tharp's recourse to channeling the anguish of destruction and chaos to produce and promote its conversion into art participates in the mythopoetic enterprise -- that is the making of new myths relevant to the present day from the most vibrant myths and icons of the past.

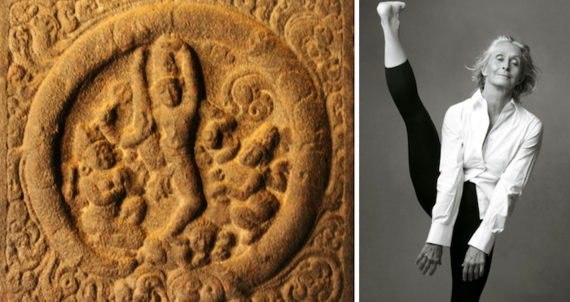

It is no accident that Tharp would recall Indian mythology, given that one of the most renowned and artistically serene representations of a god created by any race is that ubiquitous Indian icon of the Hindu god Shiva dancing within a ring of fire symbolizing the center of the universe while mediating creation and destruction, with each necessitating the other. Known as Shiva Nataraja, the lord of the cosmic dance, he is a figure whose magnificent rhythmic motion is attributed by the Hindu mystics to be the source of all movement and events throughout the universe.

In all the world there is likely no more accomplished and renowned conflation of the Apollonian and the Dionysian, or the Sublimation and Desublimation principles, invested in one mythic being, deity or human, as can be found in the embodiment of Shiva Nataraja. As with the Greek gods, Shiva is the lord of the Dance, but in his case it is the all-consuming cosmic dance from which there can be no debauchery or destruction removed from the divine effects of cyclical creation, preservation and destruction that Shiva represents. But there also can be no discipline too ethereal or refined for the human embodiment of the godly impulse in all men and women, as all creation in formation and dissolution is encompassed by the dance of Shiva, and other gods of dance such as the goddess Kali. It is no accident or coincidence that both Shiva and Kali have both creator and destroyer aspects, as destruction is necessary for renewed and perpetual creation, or in the current zeitgeist terminology, for a sustainability achievable only through efficient natural processes that facilitate death and decay in their turns with birth and growth.

It may seem like a grand overstatement of Tharp's intent, but in fact in more human and secular ways, Tharp is employing the same mythopoetic process as that employed by the devotees to Shiva Nataraja who believe the sacred dance of the cosmos can in smaller human ways be applied to healing the trauma and adapting to the consequences of overwhelming chaos. We customarily call this process a catharsis, a working out or purging of trauma and the sense of profound loss in a series of small rituals that over time enable us to heal and to move forward with our lives. The concept of catharsis that comes to us from Aristotle's Poetics also was formulated as a justification for publicly staging tragedies that recall and incite anguish so to identify what must be purged from the body and mind to promote the health of the individual and the society. Tharp, like many of her contemporaries may dispense with the staging of tragedy and skip straight to catharsis supplied through dance as a collective ritual enabling us to cope with tragedy in it numerous visitations. There is no more valid justification for simple entertainment than catharsis, but neither is there a better account as to why the more complex arts are the more advanced means for completing the cathartic effort with high-minded ideals. The choreographer and the dancers heal through their ritualized and repetition of entertainment, then supply a more sustained enlightenment through art. Yowzie heals in making us laugh at our own follies, then sustains our minds by asking us to consider why we have socially advanced to a place that we can look in detached amusement upon our flaws.

It is the meditation on the more artful aspects of Yowzie as a stark contrast to Preludes and Fugues that Tharp ultimately wages we will consider. Instead of concentrating on the alleviation of trauma through the methodical exercise of discipline as in Preludes and Fugues, Tharp makes us look at what happens to us when we abandon discipline and social principle to worship at the altar of hedonism. Here too there is a steep art historical legacy, this one by all appearances informs Yowzie even if only subliminally. That is the tradition of depicting the bacchanalia, for Yowzie is one such revelry in the "pagan" (or agnostic) sense of being without a foundation in any truth, but in the Dionysian model seeking the desirable oblivion of intoxication.

When seeking to understand the bacchanalia we must remember that beneath the hedonistic pleasures that promise to drown our sorrows is the deeply submerged, indeed the strongly repressed, desire to attain the death that is release. The bacchanal starts out as an adventure, as a celebration, as a distraction, but ultimately, as the drunken tears proceed, the Dionysian remembers the pain and with that memory comes the desire for an end that is final, with the promise of an afterlife or reincarnation left stillborn. The worship of Dionysius is not a mystical transcendence. It is a debauchery meant to cancel out the sacred, the godly, the moral -- whatever higher authority is perceived as victimizing the tortured soul. To Tharp's credit, she never lets Yowzie become so sanguine. Her intent after all isn't to make us feel the pain of lost souls. For this reason beginning her performances with the exercises of Bach encourages us with its foresight of the alternatives we should remember as we watch the hedonistic display of surrender unfold.

Ultimately, the Protestantism of Preludes and Fugues and the hedonism of Yowzie both must surrender to the greatest dance of all. Tharp may not have explicitly portrayed the Danse Macabre that acknowledges the universal submission to death, but it is implied as the consequence in the Dionysian dance of Tharp's hedonistic subjects. The medieval mind may have been limited in its scientific capacity (where today even the study of Chaos is a science), but medieval, and likely all premoderns, were more realistic than we are today in knowing what to expect of death. The Dance of Death was not literal. Nor was it merely an artistic anthropomorphism. It was the embodiment of a wish for a democracy free of hierarchies of power made real upon the arrival of the great unifier of humankind without consideration of race, creed, ideology or station in life.

The medieval proclivity for both personifying and comically endowing a human-skeletal Death as choreographer of the final dance to the grave is perhaps more enlightened than our modern relegation of death as an amorphous, impersonal declination that can throughout life be stayed with age-defying surgeries, injections and cosmetics and postponed with hospital ventilation, circulation and feeding machines. Whereas the medieval dance of death, danced by commoners and nobility alike on popular religious feasts and painted in masterpieces -- originally displayed in churches or the illuminations of manuscripts and today preserved in museums -- counseled its cults on the vanities of youth, glory and power in precisely the same ironic and modest reflection as that which the discerning viewer spies stalking the dancers throughout Yowzie.

Listen to G. Roger Denson interviewed by Brainard Carey on Yale University Radio.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.