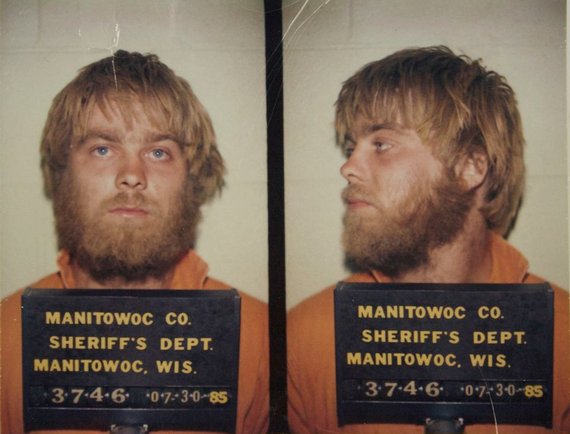

I binged Making a Murderer in a single 24-hour period and loved every second of it. But at this point the Internet has become so saturated with MAM speculation, listicles and memes, that I don't want to offer my own analysis. I don't want to talk about why I think Steven Avery is or isn't guilty, who I think actually killed Teresa Halbach, or whether Brendan Dassey was tricked into a false confession. Instead I want to talk about the genre of true crime itself. How did I become so obsessed with murder mystery documentaries and why do millions of other people, especially women, seem to share my infatuation?

On any given evening, it's not uncommon to find me sitting on the couch in my oversized cat sweatshirt, sipping a glass of wine, completely absorbed in a true crime documentary. When I get home from work I morph into a 65-year-old retiree who just finished a long day of scrapbooking and needs to relax with a glass of chard and a bit of Investigation Discovery. This transformation into complete true crime junkie didn't happen overnight, but the rate at which I became so utterly hypnotized by this class of storytelling has left me with a lot of questions.

As it did for many of my fellow true crime fanatics, it all started with Serial at the end of 2014. Sure I had dabbled in episodes of Snapped, 48-hour Mystery and Dateline on many occasions before, but the obsession really became apparent after indulging in Serial. Once Serial ended I found myself craving more real-life murder mysteries. I wanted something perplexing and thrilling, but also dark and complex. I was ecstatic when The Jinx was released on HBO. It was exactly what I had been looking for to fill the true crime void in my soul.

But what exactly is it about these docu-series that I find so captivating? A common theory is that true crime became so popular because we're often presented with a sympathetic protagonist who's been wronged by the law. We're riddled with anger at the obstruction of justice and a corrupt legal system. This is certainly the case with Serial and Making a Murderer, where the possibility of a wrongful conviction is a central part of the plot. But this is not the case in The Jinx. In fact, the thrilling part of The Jinx is the complete opposite. I quickly assumed Robert Durst the evil villain and hoped he would be convicted so justice could be served by the end of the series.

So if the protagonist's guilty or not guilty status bears no influence on our obsession with the true crime genre, what is the central draw? And why does the genre seem to peak the interest of women over men? Investigation Discovery, the 24-hour true crime cable network, is one of the most popular cable channels in the country among women ages 24-54. It is here you can surround yourself with tales of horror and witness some of the most appalling acts ever committed by human beings, 24 hours a day.

My initial thoughts on why I would choose to spend so many hours of my life absorbed in these gruesome narratives is that perhaps I'm learning how to prevent them from happening to myself. I want to get inside the mind of a rapist and/or killer so I know what to look for. As this Jezebel article points out this is indeed the reason why some women watch true crime. It's thrilling to know that these stories are true and they happened to women just like us, but it's also very scary and we should view them as cautionary tales. And once the paranoia sets in it only perpetuates the obsession because we then feel compelled to keep watching so we're prepared for any situation.

Being aware of the different types of dangerous situations I might encounter and knowing how to prevent them is one aspect of my interest in this medium, but if this is the only reason I watch true crime stories, I don't think I would choose to sit at home alone at night watching them by myself. Wouldn't I be startled by a knock at the door or a sudden rustling of wind through the trees? If these stories truly scared me, the answer is yes. This is why I can't and won't watch scary movies alone. In fact I very rarely have the desire to watch scary movies at all. But I'm not scared of true crime. Fictional horror films terrify me more than real-life tales of women being murdered.

And if the real reason women enjoy the true crime genre so much is because they're learning how to protect themselves, I don't think it would've become the pop-culture phenomenon it is today. I think the real reason we've become so obsessed with true crime is more about wanting to understand why the legal system works the way it does. Most of us have never even been in a courtroom, let alone a murder trial, and our knowledge of the legal system doesn't encompass much more than a few episodes of Law and Order or The Good Wife.

A guilty or not guilty verdict might not matter in terms of gauging our interest in a story, but the ability to critically examine our country's justice system does. Robert Durst was able to make bail every time he was arrested and hire the most powerful attorneys available because of his extreme wealth. Steven Avery was the complete opposite. Poorer than dirt and with very little resources, he didn't have many options. While the defense team he was able to hire fought hard for him, and continues to work for him informally, he is still at a great disadvantage when compared to Durst. The appeal becomes more about the intricacies of a legal system that leaves us feeling betrayed, whether it's because of a wrongful conviction or because a seemingly guilty man gets to go free.

We also need to understand the why. What circumstances could push someone to commit a truly heinous crime? It's more about a deep fascination with the human psyche than anything else, and this might be where the appeal to women plays a big part. Many women, whether by nature or by pressure from society, feel they must act as nurturers and caregivers with an obligation to be responsible for others. I think we want to understand how someone gets to the point of instability where they're capable of committing rape and murder. We can't fathom letting it happen to someone we know, or even worse, someone whose livelihood depends on us, so we need to examine it from an outside perspective.

But beyond the desire to understand the details of who and why and how, I'm also left wondering if the entire genre of true crime as a whole is just totally immoral. As Kathryn Schulz points out in her recent New Yorker article, true crime puts someone's real life tragedy on display for entertainment purposes. The tragedy of a few becomes a spectacle for millions. It's understandable why a man claiming to be the younger brother of the Serial murder victim Hae Min Lee, chose not to answer any questions at the time, reminding fans of the podcast that, to him, "this is real life." So too did the Halbach family choose not to participate in the Making a Murderer series, even though courtroom and news footage of them was available for the filmmakers to use, which they did in nearly every episode.

These families suffered the death of a loved one at the hands of a violent crime and we're sitting on our couches binge-watching the details and passing judgment on who the villains and heroes are as if they don't exist in the real world. Do filmmakers have a moral obligation not to make documentaries about violent criminals and their victims?

As Schulz points out, "This is not to suggest that reporting on violence is always morally abhorrent. Crimes themselves vary widely, as does crime coverage, and it is reasonable to hold that at some point the demands of private grief are outweighed by the public good." However, Making a Murderer and Serial don't focus much on our moral obligation toward the victim's family. We've permitted ourselves to freely saturate the Internet with our opinions, our fan art and our tumblrs dedicated to normcore defense lawyers. And I realized that throughout my true crime obsession and MAM binging, I've never really thought about what the Halbach family is feeling now that Teresa's murder has been brought into the spotlight on an international scale. I don't think many people have.

I don't know if we'll ever pinpoint all the reasons why true crime has become such a sensation, but as we inevitably continue to indulge ourselves, we must make sure we consider that real people experienced a significant loss in every single one of these stories. We must be respectful of that.