You've got to admit, it was a weird anniversary to celebrate. There was the Mayor of NY at the Old Town Bar in Union Square - happily reminding the bar patrons that ten years ago he had really pissed them off. It was a decade ago that New York enacted the Smoke-Free Air Act. You may remember, at the time bar owners and patrons alike thought the very nature and charm of the neighborhood bar was that grey haze that hung in the air and stuck to your clothes. Back then, Old Town owner Gerard Meagher thought the ban would put him out of business. Today, he was surprised to report that profits are up, food sales are up, and customers are happy. "It turned out to be great, not this bad thing that I thought it would be," said Meagher.

Turns out that smoking was bad for us - and clearing the air made us healthier, and happier.

But today - we're enveloped in another fog. It hangs over us, separates us from our friends and family, and even makes us sick.

It's data.Toxic Data. And left unchecked, it threatens to tear apart our basic well-being in a way that may be harder to detect and combat than cigarette smoking was back in its heyday.

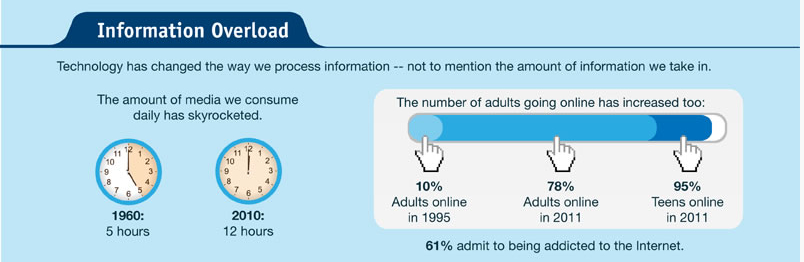

Do you think I'm overstating the impact on endless, unchecked, relentless data overload? Let's consider some facts.

University of California, Irvine professor Gloria Mark has been studying the question of how constant bombardment of digital data impacts us. She co-authored the study called "A Pace Not Dictated by Electrons." She and her team attached heart rate monitors to computer users in an office setting. People who read email were in a steady "high alert" state, with more constant heart rates. But those removed from email for five days experienced more natural, variable heart rates.

Ok, you say - email at work causes stress. No big surprise. But the data deluge is overwhelming far more than our office hours. Increasingly, it's impinging on our lives 24/7.

"People can't multitask very well, and when people say they can, they're deluding themselves," said MIT neuroscientist Earl Miller. "The brain is very good at deluding itself." Simply put, we can't focus on more than one thing at a time. What we do is shift focus, trying to manage multiple threads. "Switching from task to task, you think you're actually paying attention to everything around you at the same time. But you're actually not" said Miller. Researchers like Miller say they can actually see the brain struggling. "You cannot focus on one while doing the other. That's because of what's called interference between the two tasks" explains Miller. "They both involve communicating via speech or the written word, and so there's a lot of conflict between the two of them.

So, what do we do? First, acknowledge that being constantly in the line of fire of massive stream of data - without a coherent filter or an off switch is toxic. If you're like me you've seen your behavior change of the past few years, trying valiantly to keep up with the rising tide of pings, notifications, updates, newsletters, tweets, and friend requests. It's time to stop trying and embrace a whole new way of thinking about your information ecology.

Think of the phone. Back in the day, it rang - you stopped what you were doing and answered it. But the phone was analog. And other than a beep if a second call came in (remember 'call waiting'), it was simple to manage the phone. But today, it's like having a wall of phones all ringing at the same time - begging for your attention, each call equally important (or unimportant). One phone is your son or daughter calling from school, while the other is a telemarketer trying to sell you insurance for a car you don't own. Both rings sound the same. Thousands of rings. It is so desperately overwhelming it's going to make you sick, or sleep deprived, or both.

I asked one of the smartest people I know what we should do about Toxic Data overload, and email in particular. And she said something that seems so rational, I can't understand why it hasn't happened already. "You need to change the economics of information", said Esther  Dyson. And if anyone understands this problem it's her.

Dyson. And if anyone understands this problem it's her.

Dyson is daughter of a physicist and mathematician. A Harvard grad with a degree in economics, she is today one of the leading angel investors and thinkers in the areas of healthcare, health technologies, and space exploration. So, thinking about your broken inbox and data overload seems like something she's got the intellectual firepower to solve.

I asked Esther if we will really every change email from a fire-hose to a garden-hose?

"Well, I think it's got to happen because the market works and the non-market doesn't work. It's kind of like healthcare. It's beginning to break down and we're beginning to realize we need to pay for prevention. In a sense you could say this is email overload prevention rather than email overload remediation after the fact. Right now we're dealing with bad health in email and what we need to do is start focusing on wellness, prevention."

The challenge is to define the problem - and the solution. "The current system lets other people add things to my to-do list" says Esther. But she thinks she can use her background in economics to slow the flood. Her idea, create a tollbooth at your inbox. Ask the sender to determine how important the message is and - as she explains it - put money behind that choice. This way, "the sender pays to send mail, while the recipient can set the price" says Esther, who wrote about her vision here.

If you think about it, marketers pay to reach you now. They buy mailing lists, they print catalogs, they pay postage. But receiving email is an open floodgate, and the result is already toxic, and getting worse.

Dyson's plan would put you in charge of your inbox, and you could set up a set of lists for who can reach you, and at what price. Friends and family? Free. Business associates, .10 per email. Marketers .25. Business pitches with powerpoint files and excel spread sheets attached, $10.00.

Esther says - getting the voice right will be important. "The wording is going to have to be nice. It's not like, 'Sorry dude, Esther's too important for you. Send $10.' says Esther. "It's more like, 'This is Esther's email filtering service. We charge $10 to help you get her attention.Pay us $10 and we'll make sure your message gets through. We can't guarantee she'll answer it but she will receive it.'

The change to paid email won't be easy Dyson acknowledges. "There will be lots of glitches at the beginning, starting with people you know who have multiple e-mail addresses, old friends not on your current white list of free senders, and so on. But such challenges will diminish over time, and, as less mail gets sent, a higher proportion of it will be wanted and answered."

What Esther is proposing is a wholesale change in the way we view data, and how it flows toward us. Think of it like the advent of caller ID. Before caller ID, you picked up the phone - and took your chances that the person on the other end of the line was a friend, not a prank caller or telemarketer. Today - we have knowledge (who's calling) so we don't have to talk to strangers.

Esther's plan is just one step to us regaining control of our digital front door. Our time, our inbox, and - potentially - our sanity.

Will we look back on today's glut of unfiltered information in ten years with the same disgust and shock that we look back at cigarette smoking? Maybe. There's no doubt that without better filters and new ways to set reasonable standard as to how people can reach us, and when, we're on our way into Toxic Data Overload - a problem that technology created, and now technology can solve.

Until then - remember this: it's your digital life, and you don't have to feel guilty or overwhelmed when you can't filter the signal from the noise.

And in terms of Esther's idea - I'm in. How about you?

Graphic: Infographicarchive Photo: The World Economic Forum