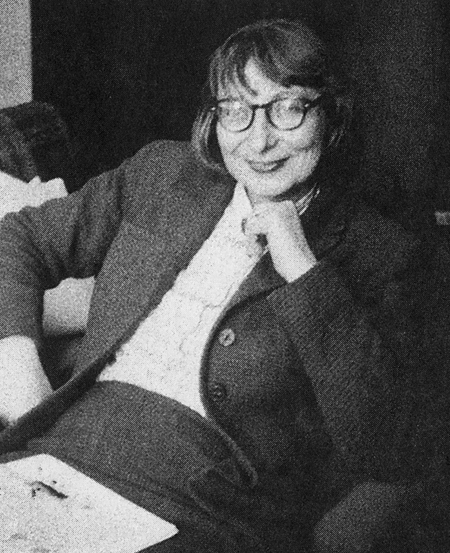

Jane Jacobs / The Jane Jacobs Estate

"There is no way of overcoming the visual boredom of big plans. It is built right into them because of the fact that big plans are the product of too few minds. If those minds are artful and caring, they can mitigate the visual boredom a bit; but at the best, only a bit. Genuine, rich diversity of the built environment is always the product of many, many different minds, and at its richest is also the product of different periods of time with their different aims and fashions. Diversity is a small scale phenomenon. It requires the collection of little plans" -- Jane Jacobs, Can Big Plans Solve the Problem of Urban Renewal?, 1981.

In Vital Little Plans, a new collection of the short writings and speeches of Jane Jacobs, one of the most influential thinkers on the built environment, editors Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring have done readers a great service. They've brought together the best of this brilliant autodidact's compelling arguments for why planners and designers must never forget the importance of small-scale diversity given it results in interesting cities created, first and foremost, for people.

In essays and speeches that range from the 1940s -- years before she became famous for The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961 -- to 2004, just two years before her death, we learn how her thinking evolved and grew more ambitious, but was always rooted in what she learned from watching people interacting on the streets.

In 1958, a few years before she published Death and Life, she writes a thoughtful piece for Fortune magazine, contrasting her experience walking through the liveliest parts of cities with the deadening urban renewal projects to come, the projects she saw as killing organic, small-scale diversity through a homogenized, imported model. Early on, she identified the faults of those vast Modernist urban design projects: "They will be spacious, park-like, and uncrowded. They will feature long green vistas. They will be stable and symmetrical and monumental. They will have all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery. And each project will very much look like the next one."

To fight these projects, she then called for urban citizens to empower themselves by thinking critically about cities and then making their thoughts heard and influence felt. "Planners and architects have a vital contribution to make, but the citizen has a more vital one. It is his city after all." Citizens must go out and really study their city. "What is needed is an observant eye, curiosity about people, and a willingness to walk."

For Jacobs, walking, and later biking, were central to experiencing that attractive diversity of city life. As such, any transportation plans that undermined walkability, that downgraded the status of the pedestrian on the street in favor of cars, were anathema to her, as we would later see in her committed advocacy to stop New York City planner Robert Moses' effort to put an expressway through her beloved Greenwich Village. Her writings in the 60s also made the case for architectural preservation, which she viewed as central to the aesthetic diversity that makes cities a visual adventure. For Jacobs, diversity in the built environment was not only an indicator of a vibrant, social place, but also economic vitality.

After leading the assault against urban renewal for multiple decades, beginning in the 1980s, she began to write more ambitious, theoretical essays that explore the "ecology of cities." For her, this was less about urban ecosystems, but the intricate dance of systems that drive innovation, that make cities the place to be not only for social and cultural life, but also make them critical economic drivers. "A natural ecosystem is defined as 'composed of physical-chemical-biological processes active within a space-time unit of any magnitude.' A city ecosystem is composed of physical-economic-ethnic processes active at a given time within a city and its close dependencies." She again relates the importance of diversity: "Both types of ecosystems -- assuming they are not barren -- require much diversity to sustain themselves. In both cases, the diversity develops organically over time, and the varied components are interdependent in complex ways. The more niches for diversity of life and livelihood in either kind of ecosystems, the greater its capacity for life."

Her speech in 1984 on the need to enhance diversity through specific policies that support multiculturalism, which in turn supports innovation, is just as important today. Analyzing her adopted city -- Toronto, Ontario, which she moved to in the early 70s -- she says: "The Canadian ideal is expressed metaphorically as the mosaic, the idea being that each piece of the mosaic helps compose the overall picture, but each piece nevertheless has an identity of its own. As a city, Toronto, has worked hard and ingeniously to give substance to this concept."

In the last years of her life, she became increasingly concerned about the future of urban development, about whether diversity, enabled by the many, many "vital small plans," would win out or be trampled by the forces of gentrification, homogenization, and governmental centralization. In the Vincent Scully Prize lecture at the National Building Museum in 2000, she identified future threats to that diversity. For example, she saw that immigrant communities could no longer afford to take root in downtowns, thereby enriching cities from within, but often landed farther out in sprawled-out suburbs that limit their positive cultural and economic impacts.

She was also fearful of the World Bank and other international development agencies, along with national and metropolitan governments, that intervene in the intricate economic life of developing world cities by investing in major infrastructure projects that can wipe out diversity on the ground. She seems to equate the "comprehensive planning efforts" of the World Bank with Robert Moses. In a talk at the World Bank in 2002, she tells their leadership that it's best to do no harm -- and not invest at all -- rather than inadvertently upset the dynamics of a balanced urban ecology. "The minute you begin to prescribe for cities' infrastructure or programs comprehensively, you try to make one size fit all."

To the end, she stayed true to what she knew: successful, vibrant, happy cities arise out of the visions of many, not the powerful few.