In this post, I'll look at Jessica Kantor's lovely 360° video work Ashes. Situating it within the context of early silent film and dance, I'll examine the role that gesture plays in the emerging narrative language of VR.

The Passion of Joan of Arc

Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1928 silent masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc offers an instructive place to begin. Dreyer's film, which combines minimal sets and costuming with an exuberant use of close ups, brilliantly demonstrated that facial gesture, which humans can read from infancy, can be an incredibly powerful and nuanced language for storytelling. Such a language is not only "universal," it harnesses the most basic of our bodily memories, that of a mother's face looming large over her child, and all the emotional connection that this memory musters. The actors' faces transmit complex information forcefully, but they do so in a way that is not easy to quantify or standardize.

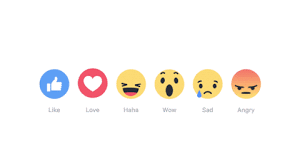

Although it may be coincidental, it is certainly not surprising that Facebook adopted "reactions" around the same time as Oculus Rift released a consumer version of its VR headset. Rather, it points to the fact that as our lives become more and more virtual, whether online or via a head mounted display (HMD), how we express ourselves and how we "read" each other is changing.

Acting as simple visual "codes, these frozen, exaggerated facial expressions standardize and render legible nuanced, complex states of mind. The goal is not to transmit the subtleties and range of interior states, as it is in Dreyer's film. Rather, in the same way that the "pinch" and "swipe" gestures of touch screens serve to efficiently transmit commands, the reactions serve "to share your reaction to a post in a quick and easy way," according to the FB press release.

Given that our ability to read another person's body language has evolved over millions of years and includes complex audio, visual, olfactory and other signals, it is impractical to expect that machines, even highly intelligent ones, will be able to fully decode or encode what we ourselves take as second nature. As our emotions and interactions are modified and translated into machine-readable, quantifiable, and writable forms, it is likely that we shall see a further codification and simplification of facial and bodily gesture. As Lakoff and Johnson suggest in their important book Metaphors We Live By, our earliest ways of conceiving of the world are through structural metaphors which reference our bodily orientation in space such as up/down and back/front. Thus, as long as we remain embodied, the emerging language of virtuality will reflect and experiment with translating this most primal of languages.

Jessica Kantor's lyrical Ashes, shown at The Tribeca Film Festival, is one recent example of a work that uses gesture and movement as a form of narrativity. Kantor not only smartly and directly references early silent cinema, she also utilizes dance, the quintessential gestural medium. In Ashes, she experiments with time and space, the virtual and the real, stitching multiple scenes in the round, thereby creating an emotionally fluid narrative. On the left, she shows a pair of lovers horsing around, playing together in the sand. In the center, the woman, having gone to get her hat, returns to find her beloved dead, his body washed ashore. On the right, the woman returns a year later to spread her dead lover's ashes. Depending on which scene one views first, the emotional tenor varies. Throughout, Kantor deftly creates and sustains a dialogue between the "real" and "virtual. In Ashes, time moves normally (forward) through the logic of the plot, as well as backwards-- the man at one point seeming to return to life and a seagull walking backwards, a magical reversal that the medium of video makes possible. However, despite the coexistence of multiple times and spaces in the film, the many footprints in the sand reminds the viewer that these virtual bodies still leave traces behind. In the real world, tragedy is not so easily evaded.

Kantor's use of exaggerated, repeated movements and emotional expressionism brings to mind Pina Bausch's dance theater. Unsurprisingly, before turning to film, Kantor was a dancer, and she does credit Bausch's work for informing this piece.

The intention was always to tell a story through movement. Before we even started rehearsing, I spent time with the dancers, showing them some other VR and watched a ton of Pina Bausch's work. As we rehearsed we took the same music but interpreted it with each of these stories separately. It was a combination of Amy and Vance (the dancers) getting to know each other, the music and the story. The dance was their improv in the moment to tell a story that was organically coming from within. Part of what inspired me so about Pina Bausch is how all of her work is based on emotion and storytelling. I found this quote from her that really sums it up: 'I'm not interested in how people move, but what moves them.' Jessica Kantor

Facebook's emphasis on the efficiency and legibility is certainly in keeping with the decreased attention span and multi-tasking that accompanies our use of digital technology (see MIT's sociometric badges for an almost Orwellian version). The reactions, also, perhaps inadvertently, resonate with earlier conceptualizations of the human body as efficient machine. Just as Frederick Taylor, father of "Taylorism," attempted to improve the efficiency of human interaction with factory machines at the beginning of the last century, Facebook provides a way to standardize, quantify, and extract the complex the emotional states and preferences of potential consumers through social media. Mocking and subverting Taylor's "scientific" labor practice, silent film stars Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin used the language of gesture to invoke the memory of bodily freedom, to play with the intrinsic limits of the body, and to undermine the move to make bodies into machines.

Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times

Interestingly, Kantor mentions that the less than optimal technical quality of much current head mounted display technology brought to mind these silent films.

Wanting to tell a story, I just couldn't stop thinking of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. The way they tackled some of the first stories in film, felt like a fun approach to try and tell a story in this new medium. Also, it worked out nicely that since the quality of playback in HMD still isn't on par with what we're use to seeing the old timey look ended up feeling very organic to the early days of VR. Jessica Kantor

This is not simply nostalgia. As Celeste Olalquiaga suggests in her book The Artificial Kingdom, "repetition is not nostalgic fixation on recovering a past, it is a pulsating preoccupation with a present far to complex to handle on a single register." As we move into viewing the world and living our lives virtually, gesture and dance offer artists like Jessica Kantor powerful ways not only to harness the expressive power of the body, but also to reveal and subvert attempts to regulate and standardize our virtual selves.

this is the second in my series on VR

If you are going to the Electronic Literature Organization Conference in June, please join me for my talk on "Narrativity in VR"