Is it possible to become accepted into the Native American tribe of my ancestor? --David C.

_________________

Many Americans believe they have at least one Native American ancestor. More than 900 nations, peoples, tribes, and bands (the terms are interchangeable) once lived on the North American continent, and more than 560 are recognized by the federal government today, with an additional 24 being recognized by states. However, an estimated 80 percent of Native American families became disconnected from each other and from their people over the years. So questions about how to become a member of a tribe are common.

The answer usually has to do with a concept called blood quantum (which we'll discuss later) and your ability to prove your Native American lineage.

Native American nations set their own enrollment criteria in constitutions, articles of incorporation, and ordinances. These can include tribal blood quantum, tribal residency, or continued contact with the tribe. The criteria vary from nation to nation, so uniform membership requirements do not exist. The key is knowing which tribe or band your ancestor most often aligned with.

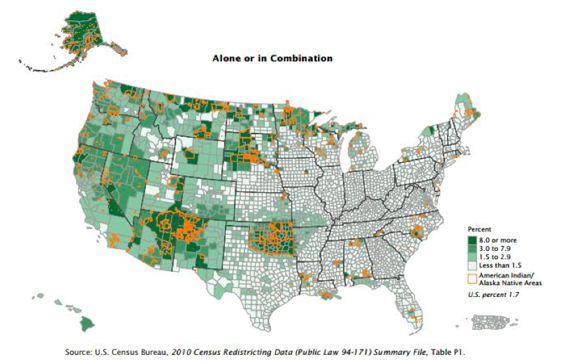

American Indian and Alaska Native as Percentage of County Population: 2010. (U.S. Census Bureau)

Searching for Your Ancestor

A good place to start your research is with the free guide to American Indian research at Ancestry, which is full of hints and strategies.

You need to track your family generation by generation until you get back to the reservation or other location where you believe your Native American ancestor lived. Using U.S. Federal Census records is the easiest way to do this research. (Ancestry has a great article on census search secrets if you want some tips.) The 1910 census included an "Indian census" at the end of each county's enumeration that lists blood quantum and tribal affiliation. These records can be gold if your ancestor appears.

Ancestry has more than two dozen record collections that may reveal your ancestor's tribe. There are also terrific collections of photos, marriage records, allotment records (referring to reservation land given to individuals by the government), and an index card file of over 800 articles and folders with information about Indians who were moved to Oklahoma.

The overwhelming majority of written records are from five Native American nations: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muskogee (Creek), and Seminole. The Federal government called these "The Five Civilized Tribes" for various reasons (one of which was the fact that they owned black slaves). Andrew K. Frank provides the following definition on the Oklahoma Historical Society website:

The term 'Five Civilized Tribes' came into use during the mid-nineteenth century to refer to the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations. Although these Indian tribes had various cultural, political, and economic connections before removal in the 1820s and 1830s, the phrase was most widely used in Indian Territory and Oklahoma.

Americans, and sometimes American Indians, called the five Southeastern nations "civilized" because they appeared to be assimilating to Anglo-American norms. The term indicated the adoption of horticulture and other European cultural patterns and institutions, including widespread Christianity, written constitutions, centralized governments, intermarriage with white Americans, market participation, literacy, animal husbandry, patrilineal descent, and even slaveholding. None of these attributes characterized all of the nations or all of the citizens that they encompassed. The term was also used to distinguish these five nations from other so-called "wild" Indians who continued to rely on hunting for survival.

Elements of 'civilization' within Southeastern Indian society predated removal. The Cherokee, for example, established a written language in 1821, a national supreme court in 1822, and a written constitution in 1827. The other four nations had similar, if less noted, developments.

Records for these five nations constitute 35-50 percent of all Native American records and 80 percent of all Native American records filmed by the National Archives. This is because in the late 19 century, the U.S. government established the Dawes Commission to oversee land redistribution within the Five Civilized Tribes. To do this, the commission attempted to create an official list of members of each nation, and required families and individuals to fill out applications for acceptance, in essence making them prove that they belonged to that particular tribe.

The Dawes Commission ended up rejecting almost two-thirds of the applications for various reasons, but census cards and application jackets were created for each applicant and are available for research, whether they were accepted or rejected. Ancestry has most of these records, as well as applications made to the Dawes Commission during an earlier attempt to enroll the tribes in 1896. (Here's an insider's tip: when you check the Dawes Census Cards,be sure to look at the front and back of each card and read all the notes. This will often lead to other cards you should check.)

The best resource for information about Native Americans other than members of these five nations is the U.S., Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940, collection on Ancestry. These censuses include 565 federally-recognized tribes besides the Five Civilized Tribes. The early censuses usually list Indian andEnglish names, gender, age, and relationship. Some have additional birth, marriage, death and relationship notations. Not every group took a census each year. Keep in mind that blood quantum was usually not added until 1930s. Blood quantum is a measurement of tribal affiliation based on ancestry. For example, a child with one Native American parent and one non-Native American parent would be considered to have one-half Native American blood. If you have three non-Native American grandparents and one Native American grandparent, your blood quantum would be .25, or one-quarter. And so on.

Location Is Key

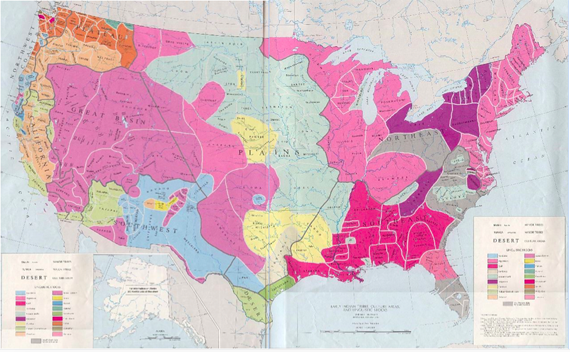

Where your ancestors lived will help you determine with which particular nation they were affiliated. Tribes were made up of "bands" of families and often formed and reformed under new leadership over the years. It was often common for a Native American man to marry outside of his nation, and associate with his wife's people going forward. Maps showing where Native American groups lived in the U.S. at specific times can be a huge help to your search.

From The National Atlas of the United States of America (Arch C. Gerlach, editor). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Geological Survey, 1970

Once you complete your research you will need to purchase the birth, death and marriage certificates (certified copies) for each generation back to the oldest Native American ancestor you can locate, to prove your direct ancestral line to them.

Case Study: Becoming a Citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

For some peculiar reason, most Americans, white or black, who believe that they descend from a Native American ancestor believe that that ancestor was Cherokee, so let's use Cherokee records for a case study.

Let's say you wanted to become a member of the Cherokee Nation. How would you go about it? Well, first, Cherokee Nation citizenship requires that you have at least one direct Cherokee ancestor listed on the Dawes Final Rolls. This roll (census, really) was taken between 1899 and 1914 and lists Indians, white citizens, and black Freedmen (former slaves) residing in what was known as "Indian Territory" (now northeastern Oklahoma). If your ancestor did not live in this area during that time period, they will not be listed on the Dawes Rolls. Certain requirements had to be met in order to be placed on the Dawes Roll, such as being listed on previous Cherokee rolls and a proven residency in the Cherokee Nation. Many modern-day applicants do not qualify for citizenship because their ancestors did not meet the enrollment requirements of the Dawes Commission and were not listed on the Dawes Rolls.

If you do find your ancestor listed on the Dawes Final Rolls, your next step is to obtain certified birth, marriage, and death certificates proving your lineage to that person. After you have obtained the necessary documents, contact the Cherokee Registration officer in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, to obtain an application to become a member of the nation.

Unfortunately, unless you can find your ancestor's name on an official tribal roll, you will probably not be eligible for membership. Remember, too, that some Native Americans in the 1800s did not remain with their nation when they were moved to reservations or assimilated into the larger American society. Either of these facts can make it much more difficult for you to establish a direct Native American ancestral connection. Of course, this doesn't mean you don't have Native American ancestry. In fact, we encourage you to take a DNA test which will show your percentage of Native American ancestry (but not a specific tribal affiliation or connection), over the last few hundred years. Establishing the DNA basis of Native American identity is fairly straightforward. But using archival records to prove specific Native American ancestry--that is, a connection to one particular group or nation--takes some legwork, and sometimes a little luck, but reconnecting with that heritage can be a source of pride for generations to come, even if you aren't able to join a particular nation.