Forty years in, the war on drugs has done almost nothing to prevent drugs from being sold or used, but it has nonetheless created a little-known surveillance state in America's most disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Alice Goffman, On the Run, Fugitive Life in an American City

The need for accessible entrepreneurship training and education within American correctional institutions is a topic slowly making its way into public consciousness. This awareness may stem from a growing understanding of the nation's mass-incarceration dilemma and the social, political and economic forces behind our prison-industrial complex. It may also be in response to our national education crisis and current debates over the legalization and decriminalization of drugs. Or perhaps this subject is becoming increasingly significant due to the growing evidence that when entrepreneurship education and training are applied, so far, they seem to work.

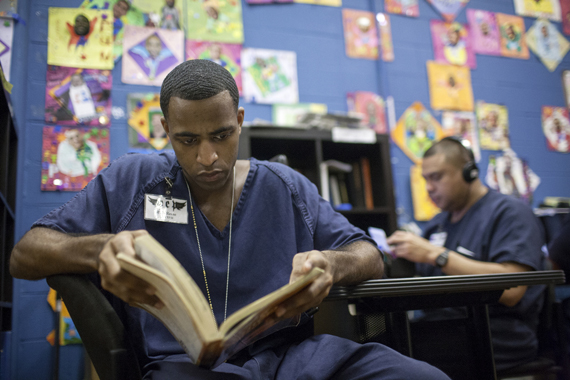

Inmates participating in the Prison Entrepreneurship Program (www.pep.org) (Image source)

In May 2013, I began a research project, delving into the approximately 500 letters I had received from incarcerated men from around the country, collected between years 2009 and 2013. These letters arrived in response to my book, The Young Entrepreneur's Guide to Starting and Running a Business, which I donated to men's prisons throughout New York and the nation starting in 1993.

I have received thousands of letters ever since. And once I began researching them with my research partner Meredith-Lyn Avey (in addition to Meredith's work in prisons, she is very involved with www.avodahdance.org), we began to realize that these letters were not only requests for more entrepreneurial knowledge. They were valuable reports directly from those men (most of them young men) who are rarely heard from, those who have been silenced by incarceration.

The author's book The Young Entrepreneur's Guide to Starting and Running a Business

Steve Mariotti: Meredith, tell us a little bit about your background and how you became drawn to prison education.

Meredith-Lyn Avey: I have been teaching creative movement classes in women's prisons for around five and a half years now with a New York City-based nonprofit dance company called Avodah Dance. The company has been facilitating workshops and residencies for over a decade in correctional institutions in Delaware, Connecticut and New York.

Since my first prison encounter I was initially struck by several things: the operational mechanisms that were employed or the structure of how a prison is run--a very militant manner; the difference of racial makeup and gender proportionality of the inmates and the correctional officers (depending on what facility we visited); the overall racial makeup of inmates--being predominantly African American women; and the juxtaposition of prison and rehabilitation.

But, what hit me the hardest were the women themselves, who were so willing to be a part of something creative--something they have described to me as "normal." The women were so full of their own creative energy and ideas during our workshops, yet I had to witness them return everyday to their lives as an incarcerated person. So, I wanted to know more about the system and started to follow authors and scholars vocal on the subject of the United State's prison industrial complex.

I was privileged to be given a copy of I'll Fly Away, by Wally Lamb, one of my favorite authors who teaches a writing course at one of the prisons we visit, which really kick started my interest in education within prisons it's necessity. I then read Angela Davis' book, Are Prisons Obsolete? and then Michelle Alexander's book, The New Jim Crow, and started to research public education reform in grad school. I never thought that my initial career as a dancer would lead me towards this issue let alone this research project!

- the interruption of education;

- activities surrounding drugs;

- age and racial identification;

- the impacts of poverty and economic hardship; and,

- self-empowerment.

From this collection, I identified 76 letters that not only touched on these very topics but also cleverly tied them into a larger social dilemma.

This is not to say that these men may be innocent of a crime. But, these 76 letters express inequities within our current criminal justice and prison systems that we both agreed need to be addressed.

Mass incarceration (source).

What struck us at the core was that we found a consistent, significant relationship between incarceration and the interruption of education before, during, and after incarceration. The letters contained one story after another from prisoners who had dropped out, and lost faith or interest in education.

Consistently, they reported their disconnect toward our education system in large part because the education they were receiving did not address their most critical need: to make money in order to survive. And so, they turned to other sources--most often sources involved in the illegal drug trade.

SM: Besides the disconnect and disengagement from education that was expressed by the prison writers, what other themes were consistent in the collection?

M-LA: Another remarkable finding is the will to overcome adversity and address what is needed during incarceration and after.

The men, specifically called on you for more knowledge on how to start and operate a legal business. They explain that since their initial taste of entrepreneurial knowledge--whether it was through a program within their facility, a workshop or donated reading material--they have embarked on a passionate quest for more information.

Dreams beyond incarceration (source)

The letters became portals into the dreams of men behind walls and bars. Yet their dreams expand beyond incarceration. Their potential is waiting untapped, ready to be utilized. Some of the men dream of bringing sustainable resources back to their communities and serving others who were once like them, at risk and on the verge of imprisonment. Some men assert that if they had been exposed to entrepreneurship education, maybe they would not have ended up in prison.

SM: Yes, it is remarkable how knowledge of entrepreneurship sparked a renewed hope in the men. With this "untapped potential," what can we do?

M-LA: Outside the prison walls, as we have spoken about in the past, there are limited resources available to make these dreams a reality. And we battle with differing public opinions encompassing the issue.

Why should we pay any attention to the voices of convicted felons?

Why should we care when we could be focusing our attention on youth populations and communities in our immediate social spheres?

Because the majority of convicted felons eventually re-enter society. Recidivism extorts billions of taxpayer dollars that could be used elsewhere instead of circulating within public and private prison corporations. We have a broken system that excuses those with financial and political power from the confines of prison--those who have committed crimes far beyond the scope of our average American dreams--yet condemn our poor young people (mainly young black men) who get caught possessing drugs and stunt their education. Our country contains the largest population of incarcerated persons in the world. The list can go on and on. So the question really is, why shouldn't we be paying attention?

*****

And its true. The list of reasons could go on and on. Meredith and I only looked at the data available to us and noted what it is telling us--that at least one option might be to bring accessible entrepreneurship education to our schools and our prisons.

Meredith; and Steve (Photo credit: Ricardo Andres)

Download the full report including our entire catalog of letters from correctional facilities across the country, and the findings that advocate for entrepreneurship education. And read my earlier articles on this topic here and here.