Nearly 60 million people around the globe are displaced from their homes due to war, conflict, and persecution. That's the highest number ever on record-- one in every 122 humans on this planet. Many refugees board overcrowded dinghies to cross the Mediterranean and reach Europe. If they make it safely to shore, they are forced into slum-like camps where they wait months, if not years, for their asylum applications to be processed.

The responsibility of sheltering refugees disproportionately falls upon poor countries. The UN's Refugee Agency estimates that 86% of the world's refugees are sheltered by developing countries such as Turkey, Pakistan, and Lebanon. Lebanon alone is single-handedly hosting around the same number of refugees who took shelter in all of Europe in 2015. And since this year's EU-Turkey deal, thousands have been deported to Turkey, where asylum seekers have reportedly been forced back into Syria and shot dead by border control.

It is a complex and difficult situation: refugees arrive in countries already stricken by economic challenges, and the systems in place to process and integrate them are not equipped to handle so many people. There are legitimate security and integration challenges host countries must grapple with to ensure safe resettlement. And the resettlement process is made more complicated by widespread misinformation, racism, and apathy.

I have followed the "refugee crisis" in Europe from my safe and distant harbor in Los Angeles for the past year. I've wondered about the humans behind the numbers, the circumstances that lead them to leave behind home and kin, and what life is like in the camps. It was with these questions in mind that I decided to volunteer at two refugee camps in Europe while leading trainings for my nonprofit this past May.

*****

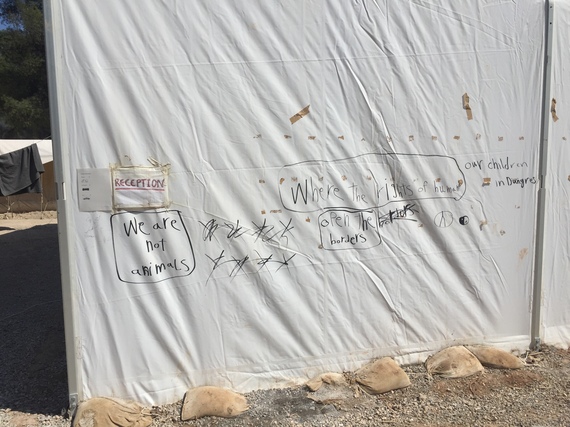

I spent my first stint at Ritsona, a camp about two hours north of Athens. Nearly 900 people live there-- about two thirds are Syrian, others are from Iraq and Afghanistan, others are stateless: Palestinian, Kurdish, and Yazidi. The camp is situated on an old military base; it has no running water or electricity, and residents live in tents with no flooring. Many have built stoves out of mud and dirt and tapped into a nearby power line to charge their phones. Volunteers from several non-profits distribute meals, clothing, and medical attention. The camp is overseen by the Greek military.

On my first walk through camp, I was met by a young girl who, upon seeing me, broke into a sprint. She locked eyes with me, opened her arms, and leapt up to hug me as she neared. I opened my arms to embrace her, caught her mid-leap, and felt her press her heart to my chest and lay her head on my shoulder.

"Hello," she said.

"Hello," I said.

She held on to me for a few moments as I continued to walk, and then she let go. I lowered her back on the ground and stopped. She caught my eyes again and squeezed my hand.

"I am your friend," she said.

I smiled. "Yes you are." She held my hand and walked with me for another minute, then ran back into the sea of tents.

*****

A few hours later I went to the warehouse to help serve meals. The lead volunteer explained how meals work: Residents are given food and water according to their family size, which is noted on their meal card. Adults get a meal, bread, and plasticware. Children get all that plus juice. If they ask for water, they get one bottle per family member.

It seemed simple enough.

There were dozens of people huddled outside the warehouse window, hollering and waving cards. I went to work, taking cards and distributing meals. Midway into my shift, a woman with gentle eyes and a warm smile handed me her card. It read: 2 adults, 3 children. I did the calculation: 5 meals, 5 breads, 3 juices. I placed all the items in a bag and handed it back to her. She took it from me, then pointed at the bottles of water behind me.

"Wah! Please, wah!"

"You want water?" She nodded her head. "Okay, one sec."

I told the volunteer hunched over the distribution papers the woman's tent number. She traced her finger down the paper and found correct tent. There was already a checkmark in the box.

"She asked for water?"

"Yes, I think so."

"Who? Which one is she?"

I pointed to the woman.

"You've already gotten your water. I can't give you anymore." The woman frowned and yelled something back in Arabic. The volunteer tapped the shoulder of one of our comrades. "Please tell her she's already gotten her water for the day."

He said something in Arabic to the woman, and then turned back to us. "She said she used the water to cook. She says she needs another bottle for her children to drink."

The lead volunteer glanced back at the dwindling piles of water bottles behind us. "I'm sorry. She's had her water for the day."

*****

A few weeks later, I went to Calais, a sprawling and squalid "jungle" of tents and improvised shelters that house an estimated five to seven thousand people on the north coast of France. The situation there is dire: tents are plagued by rats, water sources contaminated by feces, and inhabitants have been diagnosed with tuberculosis, scabies, and post-traumatic stress. On my first walk through camp, I stepped over a dead rat larger than my foot.

Many residents of the Jungle are caught in limbo on their way to to re-unite with friends or family in the UK: British immigration law has been called "inhumane" and "ludicrous." In order to be granted asylum in the UK, refugees must apply from within its borders. But there is no legal way to cross into the UK without a visa, which is near impossible to get. If they apply for asylum in another EU country, they will no longer be eligible in the UK. So they wait, some refugees say "like animals," in the Jungle.

I spent my first evening in Calais helping residents practice English in the camp's library. The practice sessions -- more casual chit chats than formal lessons -- were held in a big tent called "Jungle Books" that's lined with boxes full of children's books from the '80s. My first practice partner was a young man from Sudan with a soft voice and piercing gaze.

We exchanged formal greetings: "Hello," "How are you?", "Were do you come from?" When I told him I'd just come from London, he smiled and said his favorite professor works at a university there.

"Oh," I said, "What subject does he study?"

"He researches the causes of social inequality. Why some people are very rich and some people are very poor."

"That sounds interesting. What is your take on it? Why do you think social inequality exists?"

"It is very complicated. Some people work very hard and have nothing. Some people do not work at all and are very rich. It is not laziness. When you have no power, no matter how hard you work you cannot be rich."

*****

Later I shared laughs and travel stories with a young man from Afghanistan. He had the poshest haircut I think I've ever seen. He told me about his year learning English in Denmark, where the summer days were very long and winter days saw almost no light. We discussed our favorite cities in Italy, and I tried to explain the difference between a hipster and a cowboy. When I asked about family and his home back in Afghanistan, his smile faded and his eyes got dark. "It is very bad," he said. "My family -- they are afraid to leave."

"May I ask, why did you leave?" I asked.

"Because I did not want to work for Daesh (ISIS). They - what's the word? Where they hurt you if...?"

"Threaten? Blackmail?"

"Yes, threaten. They threaten me. They say I must fight with them or they kill me. There was no other way."

He told me of being harassed by Daesh on the streets near the shop where he used to work. He told me of leaving his younger sisters behind, of crossing the sea from Libya to Italy and walking hours by moonlight to make it to "the hellhole" of Calais. He told me of being beat and locked up by French police for being outside of camp after dark.

I asked him what is next for him. "I never know tomorrow. Today, I am here and you are here. Tomorrow, who knows?"

*****

During my days in the camps I chopped wood, cooked and distributed meals, and practiced English with new friends. During the nights I slept with my head on a feather pillow in a hotel. Yesterday, I arrived home to a spacious apartment in Venice Beach and watched Game of Thrones until I fell asleep. This morning, my young friend in Ritsona awoke on her palette in a dusty tent with no clear path to a safe and permanent home.

It was not until last night, upon arriving back in Los Angeles that I finally cried. I cried for the Syrian woman who watched her sister drown when their boat overturned on the way to Greece. I cried for the Palestinian man I met -- just a few years younger than me -- who had lived his entire life in refugee camps. I cried for the little girl who pressed her heart against mine, and the charismatic boy with the posh haircut. I cried because their situation is incomprehensible.

I keep asking myself what put me on the inside of that warehouse, and the woman on the outside. Why was I born in a country that (mostly) recognizes and protects the rights of its citizens, and she in one where women are raped, tortured, and beheaded for speaking against the government? It seems a fruitless question, I know. But one that I hope we ask ourselves before setting policies.

When I was a little girl, my mother used to repeat a quotation from the late protestant pastor and social justice advocate, Martin Niemöller, who spoke out against Adolf Hitler before being sent to concentration camps. She said it every night before bed, a strange nursery rhyme of sorts:

"First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out-

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out-

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out-

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me--and there was no one left to speak for me."

I did not know what a trade unionist was, but I understood the sentiment. Our humanity is bound up in one another's. There can be no sustainable peace within our walls if they only serve to keep injustice out. Today, in this life, I am on this side of the walls. But, oh how unpredictable life can be. Like my Afghan friend said, "Today I am here and you are here. Tomorrow, who knows?"

I hope if I ever find myself on the other side of a wall, there is a kind human being there to receive me.