Soon Louisiana will have a governor named Edwards or one who is a philanderer -- but, for a change, not both at the same time.

Edwin Edwards once embodied the politics of Louisiana. A charming south Louisiana Democrat, he once bragged, "the only way I can lose an election in Louisiana is to be caught in bed with a dead girl or a live boy." The 'Silver Fox' won four elections for governor from 1971 to 1991 despite being plagued by scandals. Now, with realignment to the GOP, his legacy is split in the coming runoff. Another Edwards of no relation to Edwin -- state Rep. John Bel Edwards -- is the moderate Democratic candidate, opposed by a skillful yet unpopular philanderer, Republican Sen. David Vitter.

Polls, Possibilities, Probabilities: John Bel Edwards has consistently led Vitter in public and internal tracking polls since the October 24 primary. His margins vary from 7 to 22 percentage points depending on the poll. Polls showing large Edwards' leads usually have more heavily minority and Democratic samples than those showing narrower leads.

Nine months ago Edwards was given little chance to win the election. Vitter began the cycle with a seemingly insurmountable lead. New Orleans Times-Picayune columnist and blogger Bob Mann wrote that the best hope to beat Vitter would be for Democrats to vote en masse for a moderate Republican. Mann was not alone in this assessment. The political environment had turned decidedly against Democrats, and Vitter, despite personal flaws, was deemed politically bulletproof. Additional scandals emerged throughout the campaign, though, and Vitter finished 16 percentage points behind Edwards in the initial primary. Just days before the runoff he is still down significantly in nearly every poll.

It is hard to imagine how Vitter overcomes his deficit. Louisiana's open primary system generally favors frontrunners. A candidate who enjoys solid support in the initial primary -- like Edwards -- and also a large lead -- like Edwards -- nearly always wins the runoff. To defeat such a front-runner requires a complete consolidation of the non-frontrunner vote. Vitter starts with a very low share of the non-frontrunner vote, and also a lack of enthusiasm for him among other Republicans. This does not bode well for second-place finishers in runoffs.

But as happens every election cycle, polling is doubted in the face of uncertainty. An Edwards win doesn't fit two decades of southern Republican realignment narrative. The recent failure of the polling in Kentucky is given as evidence that the polls are flawed for not capturing the election of tea party outsider Matt Bevin over Democratic frontrunner Jack Conway.

In Kentucky, turnout was lower than expected, thereby breaking the sampling frame - as one Kentucky pollster observed to us, "no one knew how to poll 29 percent turnout."

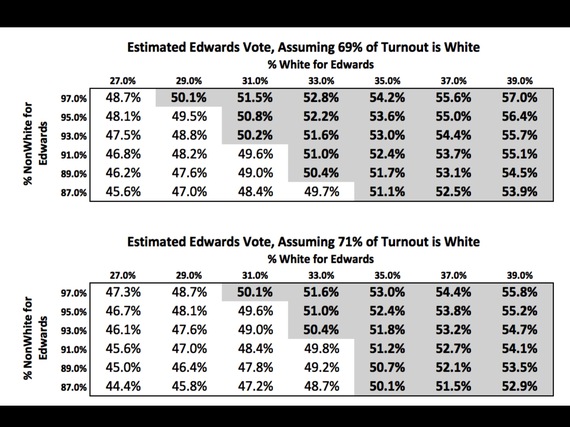

The Louisiana polls are also sensitive to the turnout formula, particularly with respect to race. Let's start with two assumptions: first, Edwards holds 95 percent of the non-white, largely African American, vote; second, Vitter wins 69 percent of the white vote. These proportions are typical for recent Louisiana elections. In this scenario the runoff strategy for Edwards is based on the number 31 -- he needs 31 percent of the white vote, and he needs 31 percent of the voters to be nonwhite, as they were in the primary. If Edwards meets or beats these two 31s, he wins. If, however, either his white vote share falls to 29 percent or his black share drops to 91 percent, Vitter wins. If the overall electorate falls to 29 percent nonwhite, then Edwards loses.

Analyses of early voting in Louisiana indicate that turnout will likely be higher than in the primary, increasing from 39 percent to 44 percent. And the electorate will be more Democratic and more African-American, according to early voting data, These are ominous signs for David Vitter. Runoff turnout surges are more common in Louisiana, and usually result from increased black voter participation in the second round. The Louisiana Troopers Association endorsement of John Bel Edwards likely solidified the frontrunner's level of support among whites -- which has run between 34 percent and 38 percent across public polls and in private tracking polls.

The Fragility of Teflon: Vitter's facade of invulnerability was also self-created. In his first election after the prostitution scandal in 2010, Vitter easily defeated 'blue dog' Representative Charlie Melancon. Melancon had well-earned reputation as a deal-maker. He was a businessman in the state's critical sugar industry. The downside for Melancon was that he was running in the first Obama midterm election and never could gain any traction against national Republican tides. The formula for Vitter was simple - run against Barack Obama. More to the point, Vitter demonstrated how a disliked candidate can run and win. He built strong well-tuned campaign organizations and he was remarkably disciplined. Indeed, his response to the prostitution scandal -- first alleged in 2002 and affirmed in 2007 -- should be taught in classrooms about how to move past a scandal. His effort on Monday to turn the event in Paris and capitalize on the call to block accepting Syrian refugees is consistent with his past strategy.

During the 2015 election, the scandal reemerged as an issue. But scandal alone has rarely been enough to fell a Louisiana politician, and this scandal has never seemed to hurt Vitter before. In this case, though, the scandal came up late in a divisive primary campaign. In Kentucky, Bevin also faced a divisive primary, but that was six months before the general election. Time heals divisive primary wounds. Vitter comes into the runoff with fresh wounds. And, Louisiana also confronts something approximating government failure under GOP Governor Bobby Jindal. Jindal and Vitter are rivals, but to voters they look as though they are made from the same cloth -- and Vitter is therefore stained by Jindal's ambitions and his failures.

Other Uncertainties: It is also possible that Republican voters who didn't back Vitter in the initial primary are telling pollsters that they want to vote for Edwards but won't actually do that when they step into the booth. This presumes that Vitter can turn his opponent into Barack Obama, his old formula for success. John Bel Edwards took steps to immediately inoculate against this strategy, by painting the choice for Louisianans as "prostitutes over patriots" and thereby getting his military experience, pro-life identity, and moderate politics out in stark contrast to Vitter's known associations.

Candidates up by as much as Edwards is over the faltering Vitter generally don't go negative. So the prospect of a close finish cannot be discounted, even though we have yet to see any evidence in the electorate that the polls' turnout frame is broken or that Vitter has consolidated the white vote to levels even close to what he would need to win.

For Democrats in running deep red states, there is a lesson here. Republican divisions may create opportunities for victories, but the path is narrow requiring both a flawed Republican nominee and a divided GOP.