Once again, leave the glory of the French capital and head to Marseille if you want a fresh insight not only on how France became France but still more on the role art, science, graphics and design together helped develop the Arab rage that is coming home to roost across the western world. There, in one of Europe's most creative museums, the MuCEM, you'll find a stunning show: Made in Algeria: Geneology of a Territory.

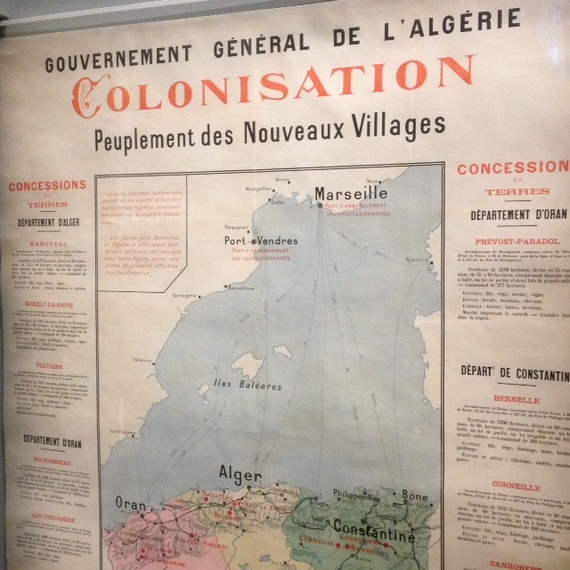

It is a subtle, nuanced history of empire and colony, how the French in alliance with Spaniards and Italians, conquered a land four times the size of France and remade it as a laboratory for everything from pharmaceutical testing to urban design to jurisprudence. It all begins with glorious maps and landscapes that portrayed the Algerian territory and sold the Algerian territory to Europeans as a vast empty space--much as Americans sold the "wild west" as an empty continent where no real people--just Indians--lived.

Though the war for Algerian independence has been over for half a century, it's still a raw and sensitive subject for many French--as I discovered one morning in my neighborhood café. I was sitting at the bar sipping my expresso when I mentioned a new found historical item: after the war was over, only one architect remained in the old colony

"Bah, of course," sputtered my bar-neighbor. "The French were forced out" as though it were inconceivable that that this land might have had actual Algerian. But that was not all. His round white bearded head was growing red with rage. "Algeria was not a colony. It was France, a department of France!" he expectorated drawing all the other heads in the café toward us.

There was a sliver of accuracy in his sputtering declaration. General De Gaulle had identified labeled most of Algeria as French departments after World War II, but in fact as all serious historians have noted they were at best second class departments in which a maximum of 40,000 Algerians who "merited" French citizenship were granted French papers. The rest of the population had no legal papers at all.

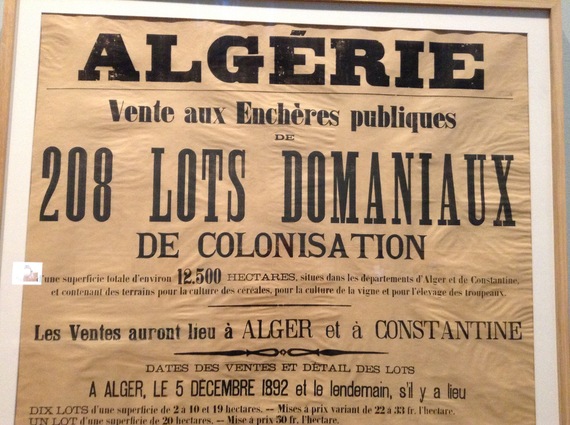

My bar-mate, who never deigned speak to me again though he was there most every morning, would have done well to visit the MuCEM exhibit, not least the colonization recruitment posters that had been plastered an walls all over Paris well into the 20th Century.

Large, bold type at the bottom of those posters left no doubt that the land that mother France was selling to the would be colonists was strictly reserved to French or European people. Actual Algerians need not apply.

As much as it presents the story of colony and empire won and lost, this exhibit captures intimately the strange, often displaced, romance that a great power harbored in its conquete civilisatrice -what it imagined its colonial mission was as much as it erased the reality and history of those it was colonizing.

As curator Zahia Rahmani, a native Algerian and art historian living in France put it,

"The idea of modernity was everywhere. Pharmaceuticals, vaccines, treatment of illnesses, eye diseases, skin diseases." Many of the epidemics that swept French Algeria were due to the installation of northerners who had no resistance to local illnesses, but managing those epidemics meant that the mixture of Europeans and Arabs amounted to a sort of living medical laboratory that benefitted the France's burgeoning pharmaceutical industry--even if it did little for the Algerians.

Modernism became something of an obsession for a France dedicated buried in its reverence for ancient kings and chateaux. The vast so-called emptiness of Algeria offered a platform for invention. New formulas of cement and plaster and brickwork kept young French engineers busy ripping down the ancient coastal casbahs, building roads and lined with modern homes for the French. When there were not enough French to fill them up they recruited Spaniards and Italians to maintain, as Zahia Rahmani explained, to maintain a "correct" European demographic balance, all of them well segregated from the natives..

"They experimented with new and old materials and later with building housing along the new roads... all the so-called 'tropical' materials for buildings climatized homes" prior to the invention of air condition. At the same time the vast coastal plateaus offered new opportunities for agricultural experiment and development, models for the huge farms that would eventually displace family plots in the 1950s, employing fleets of hand labor, including school children before modern machinery had been invented.

"Enormous experiments in agriculture were undertaken including new botanic species, and we have to say as well maintaining a sort of farming that depended on hand labor to keep the actual Algerians in place. What is an agricultural worker?" Rahmani asked with a smile. "It's a human who uses his hands and not his head," again paralleling the infamous bracero system of the post-war years in California.

"The territory completely changed, the forests devastated [for wood products]. Monstrous development of tourism completely destroyed the coastal landscape" creating the first system hivernage or winter tourism--exclusively reserved for Europeans.

The most direct consequence of the Algerian social and urban development "laboratory" remains even today in the grim blockhouse housing estates that surround Paris, Marseille and Lyon to house the immigrants who came north to do the low-paid work that French natives preferred not to do, leaving the bitter taste that has turned many of the immigrants grandchildren toward jihad and drugs.

Surely, I asked Rahmani, some of those new modernist creations must have also benefited the indigenous Algerians. She thought a moment. "Yes, of course, housing and construction and road building improved along with viticulture. And of course the great 3000-mile Trans-Saharan highway linking Algeria with formerly French Niger and Nigeria. It was there on the mountainous and desert stretches of the Trans-Saharan that many of the world's car makers filmed ads demonstrating the performance solidity of their models.

Yet how much did the colonized Algerians really benefit from the great colonial laboratory? "It depends," Zahia Rahmani answered with another chuckle, "on what you mean by profiting. In 1914, well into the 20th Century, only 3 percent of Algerians went to school. But by the 1950s it had begun to improve a little bit."

All Photos of MuCEM displays by Frank Browning