When I saw "Beautiful Beast," at the New York Academy of Art, I hadn't written anything about art for a while. I've been a bit out of circulation lately -- my schedule has gotten to the point where I must often choose between painting and writing, and painting comes first of course. Seeing "Beautiful Beast" clarified and crystallized some thoughts which had been turning themselves over in my mind during my period of silence.

First, let me say that this show is very strong, and if you're in New York, it's worth checking out. Let's say that you, like me, are not entirely clear on how a curator makes his or her voice heard - just what exactly they do. Among other things, "Beautiful Beast" is an excellent primer in the art. Many pieces in it stand out on their own, but the main force of the show is as a unified whole - and this owes to the hand of the curator, Peter Drake.

Drake has clearly compiled, over the years, a mental catalogue of work which disquiets. A specific strain of disquiet speaks to him. It is neither the biological horror of Cronenberg exactly, nor the metaphysical terror of de Chirico, but somewhere in between: metaphysical unease as a result of biological disturbance. This is a show of bodies that are somehow off.

Consider Barry X Ball's "Purity," a draped bust derived from Antonio Corradini's "La Purità," with the awful addendum that it is carved from white stone with hollow reddish intrusions, so that it appears to suffer from innumerable small cyclopean wounds.

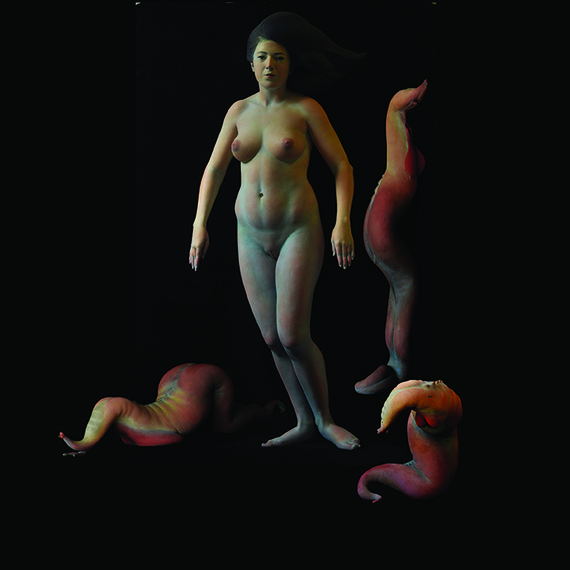

Take Judy Fox's "Mermaid," a female nude imbued with bluish patches, surrounded by three numbered "Worm" sculptures, possessed variously of breasts, spines, asses, and vulvas in a sinuously run-amuck take on human physiology.

Judy Fox, Mermaid, Worm 1, Worm 3, and Worm 7, 2011, terra cotta and casein, Mermaid 64 x 26 x 13 inches

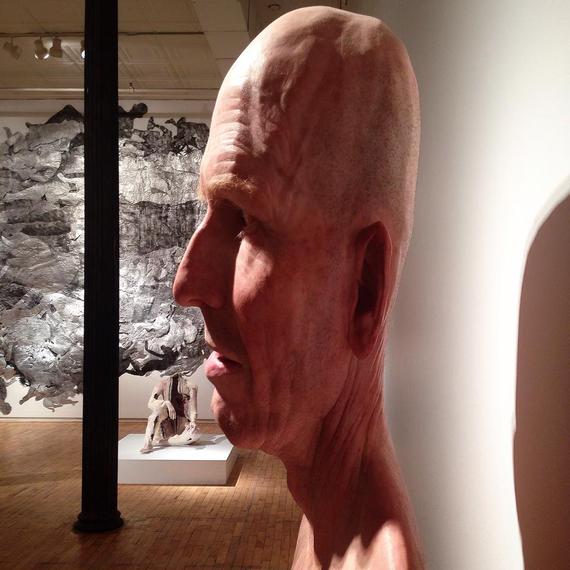

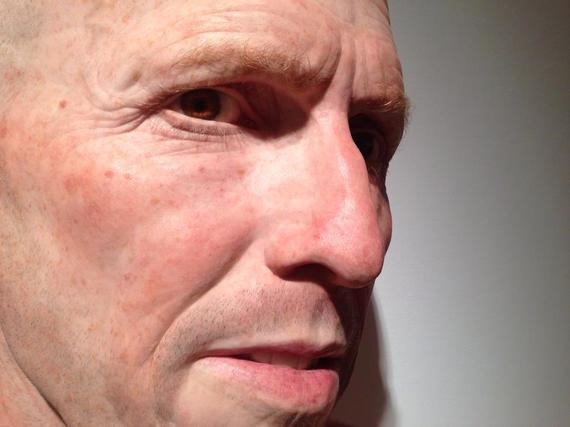

Evan Penny has a self-portrait done in the oversized hyperreal manner of Ron Mueck, with the twist that it only works from a single angle. Here it is in its frighteningly large but naturalistic aspect.

Evan Penny, Self Portrait, Variation #2, 2013, silicone, pigment, hair, 38 x 42 x 12 inches

photograph courtesy of Bonnie DeWitt

And here is the same piece revealing its compression along its other axes.

One can stand in a single spot and see this piece in comfort, but it is optically unstable in the face of any change of perspective.

Rona Pondick's "Wallaby" presents an animal in which a perfect steel finish clashes against sloppy mismatching of parts and sizes: one might say the monster itself is a clash of William Gibson and Dr. Moreau. It presents the happy-go-lucky aspect of a chimera which cannot survive.

A recent version of Eric Fischl's notorious "Tumbling Woman" is included. This 9/11 sculpture caused a ruckus when it was first unveiled; its shocking effect has softened with time, leaving behind a quieter mix of anxiety and sorrow - emotions much closer than the original ones to Drake's overall themes in this show.

Or take Kiki Smith's "Mary Magdalene," in which the penitent sinner's famously long hair, worn as clothing, has transformed into a coat of fur sprouting from her entire body. As with so much of Smith's work, she asks us to rephrase our expectations of beauty to comport with her concepts of the organic and the natural. But her method is not entirely innocent: her propositions of the organic and natural are always selected and edited to start out offputting. The friction makes her work eye-catching; it makes sure we don't miss it.

There are many more pieces, some of them very good, but you get the idea. Now, what did they contribute to the thinking I had been doing while painting without writing? Well, as usual, I had been mulling over the basics: what is the value of representation? What is the point of learning to depict the human form with high fidelity? And this show presents a visceral statement of an answer which I had only thought about in a detached and analytic way. To wit, the discipline of representation opens a vast vocabulary, a vocabulary that is endlessly specific, because it can represent many forms, and immeasurably profound, because it can join those forms with our own deepest experiences of life and the real.

This is a show that is very ambivalent about representation, and yet most of its strengths derive from the ability of its artists to represent with terrific skill and specificity. Without it, they would have nothing to fuck with. There would be only a jumble of hand-waving and intimations of upset. But the content of that upset would be empty. Consider again Ball's "Purity," juxtaposed now, as it is in the show, with his "Envy."

Barry X Ball, Envy / Purity, 2008-2012, Envy: pakistani onyx, stainless steel (23 x 17-1/4 x 9-1/2 inches)

Formally, these sculptures are more or less the same - horror-riffs on the classical bust. But without the representational capabilities Ball commands, they would mean the same thing, or nothing at all. Instead, they have full meanings, and little in common. "Purity," on the right, is a meditation on the horrors of wounds, whether from disease or stabbing. These are wounds which disturb the integrity of the body, which assault the classical unity of the figure and cause it to bleed.

"Envy," which also makes use of the interior color and structure of its stone, represents the ugliness of the Medusa as the everyday ugliness of aging (an effect enhanced from the source sculpture, Giusto Le Court's "La Invidia"; Ball's source imagery and methods are subjects for a different article). The cartilage of her face has spread to a mannish crudity. Her breasts, their mammary glands vividly represented in the yellow of the stone, are falling into a maximal sagging, wrinkling the skin beneath them and baring the ribs and pectoral muscles above. This Medusa's envy is an inconsolable craving for lost youth; she is a medusa of rot, of corruption, of the fear of decay.

Are these both busts that invoke fear of death? Yes, of course. And yet Ball represents two essentially different horrors, relying on the strength of representation to produce images that speak clearly and distinctly. They tell of different things because Ball's language - the language of "Beautiful Beast" - has a vocabulary of a hundred million words.

--

"Beautiful Beast," curated by Peter Drake and organized by Elizabeth Hobson

until March 8, 2015

Wilkinson Gallery, New York Academy of Art

111 Franklin St., NYC hours and directions here

Artist Panel: Monday, March 2, 6:30 p.m. (I have to miss this, but you shouldn't)