In his landmark book, Orientalism, the late scholar Edward Said wrote of "exteriority," a disconnect between the traveler's fantasies and reality. Reading the travelogues of French writers, Said once explained that he found "representations of the Orient had very little to do with what I knew about my own background in life."

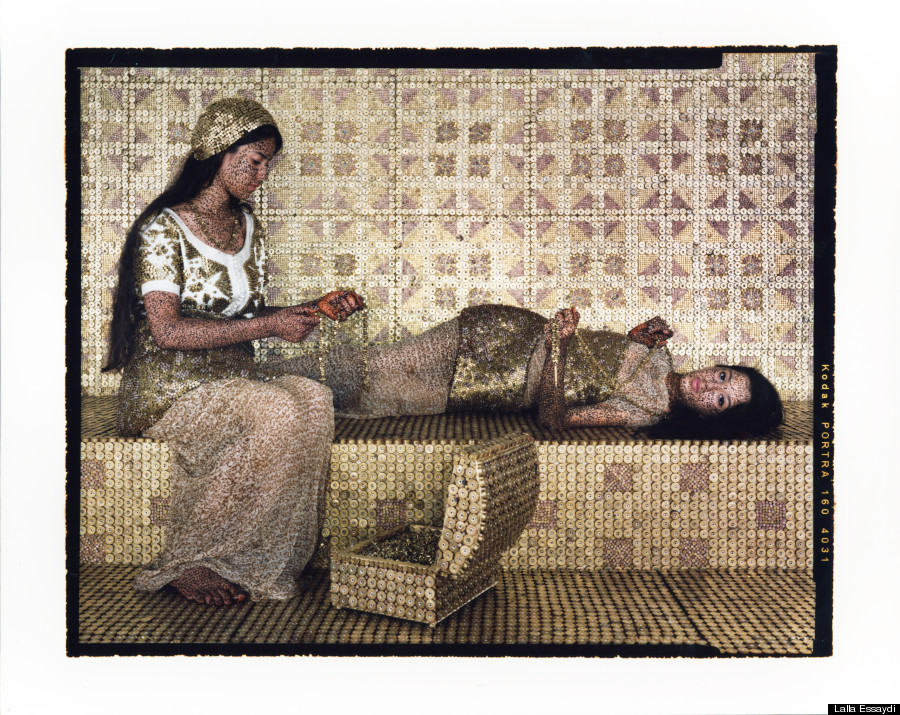

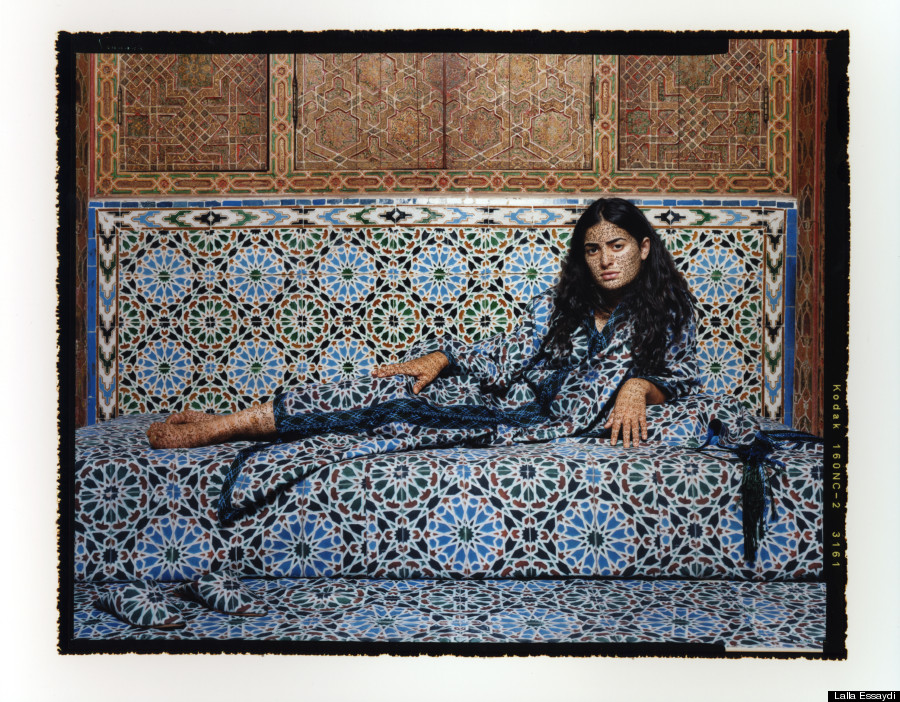

From Bullet, by Lalla Essaydi.

The work of photographer Lalla Essaydi sits somewhere inside the gaps Said felt so keenly. Part of a new wave of Moroccan artists enjoying success under the liberalized reign of King Mohammed VI (who holds some of Essaydi's pieces in his private collection), she lives in New York City and works from her family home in Morocco, a large and elaborate house dating back to the 16th century. The portraits she shoots inside -- always of women -- recall 19th century French depictions of Arab concubines, popularly known as odalisques.

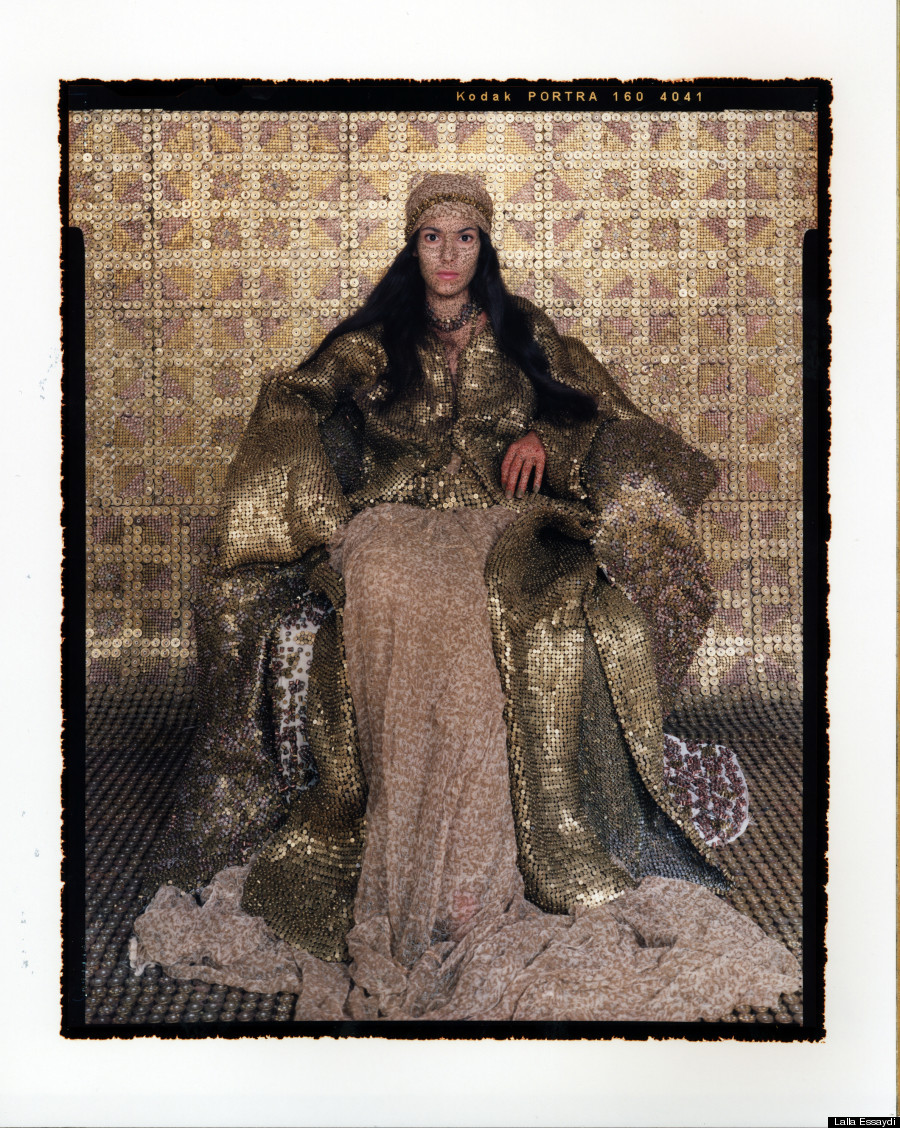

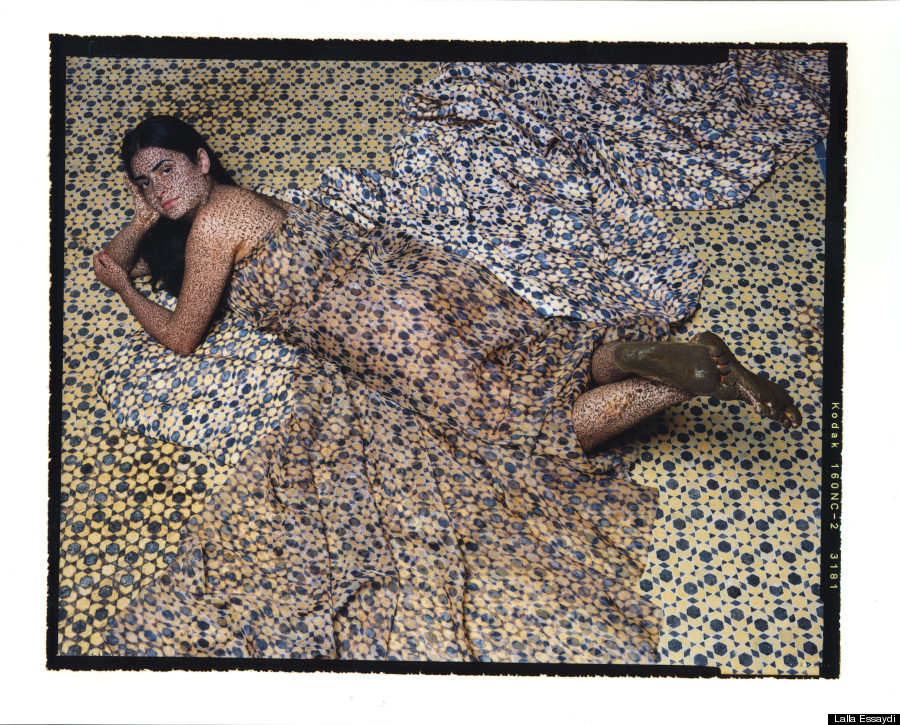

In Essaydi's portraits, you can see the ghost of the naked odalisque -- objectified even in being termed. But Essaydi's women show little flesh. They gaze into the camera, as if challenging the viewer directly. Some look positively regal, like the women in her "Bullet" series, who wear a sort of chain metal she fashioned out of flattened bullets.

From Bullet Revisited, by Lalla Essaydi.

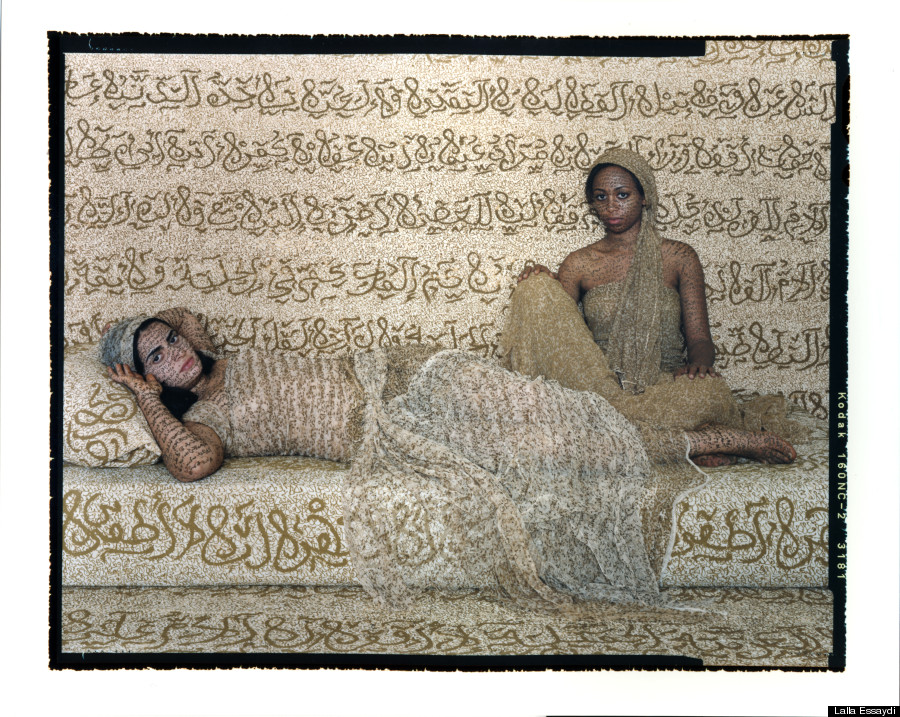

Stretches of the body not hidden under fabric are obscured by calligraphy drawn on by Essaydi herself, script that she calls "deliberately indecipherable." In much of the Arab world, calligraphy is traditionally taught exclusively to men. Essaydi uses the art form as a way to dismantle preconceptions of what women can do or be. Having trained herself in it, she adorns much of her set with henna, a dye associated with weddings and femininity. The text is a mishmash of words loosely inspired by conversations on identity she has with her subjects, who are often family members and friends. In an email to HuffPost, she explained that she writes unintelligibly, so as to throw into question distinctions between "the visual and the textual, along with the European assumption that text constitutes the best access to reality."

From Harem, by Lalla Essaydi.

She is largely inspired by the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme, a foundational 19th century Orientalist painter who famously depicted slave markets and bathhouses based on his travels to Egypt. Gérôme belonged to a tradition rooted in England and France, countries with colonies in the Middle East. For these painters working before the popularization of the camera, the aim was partly to create a historic record of the dishes, fauna, and other stuff of life so far from the West, yet still possessed by it. Along the way, they indulged in fantasies, often to do with Arab women.

From Les Femmes du Maroc Revisited, by Lalla Essaydi.

Meanwhile, Essaydi actually grew up in a technical harem; her father had multiple wives. It was while pursuing an MFA in Boston that she first encountered the Romantic documentation of her world. She saw little to relate to in the sensual scenes of half-naked women lounging on divans. Her home life had been domestic, full of children running through the halls, and moms attending to housework. Though centuries stood between her childhood and Gérôme's travels, she knew the naked bodies of harem wives were never items to be displayed. Compelled to reconcile Gérôme's vision with her reality, she began turning out bizarro, pointed reworkings of the fantasy.

From Harem, by Lalla Essaydi.

In her email, Essaydi describes a long and intensive art making process, starting with months of henna work. She and her subjects then typically "spend weeks together in old family homes, reflecting on our status as Arab women." The shoots are often held in rooms traditionally meant only for men. Simply to exist inside them can be a moving experience for the women, which Essaydi considers part of the project.

From Harem Revisited, by Lalla Essaydi.

Critics decry a new sort of Orientalism in the final images, which are breathtakingly lush, even editorial. But Essaydi sees the efforts of Gérôme and his colleagues as a response to the authentic beauty of North Africa. She says she hopes to perform a delicate balance in their wake: capturing this beauty without exploiting it. "Everything is planned carefully," she says, to the question of how visual impact determines her choices. "I won’t include anything beautiful for mere aesthetic."