Hollywood gets credit for a lot of things, both good and bad, and rightly so. It's undeniable that films influence the way the world views history and other cultures. I have heard many of my Elders say that Hollywood's portrayals of American Indians are responsible for the shallow perception most folks have of their people.

Hollywood gets credit for a lot of things, both good and bad, and rightly so. It's undeniable that films influence the way the world views history and other cultures. I have heard many of my Elders say that Hollywood's portrayals of American Indians are responsible for the shallow perception most folks have of their people.

It's hard to not see their point when you consider that in early films, American Indians were depicted as nothing more than bronzed, half-clothed savages, sporting the stereotypical double braids, screaming Ayyyyaaaayayaaaaa as they got shot off their horses by the White heroes. It's almost comical now, but that is the only Hollywood image of American Indians I recall from growing up, until the mid- to late-1970s; and that is the image we exported to the entire world.

In early Hollywood Westerns, most of the background Indians were real Navajo people. There was a colony of Navajo Indians, living traditionally in a camp in Malibu, who were on studio pay. When Indians of any tribe were needed for a western, a bus would pull up and load up for their background work. That is why in all those films, most of the time the language you hear spoken is "Dine," one of the Athapascan dialects of the Navajo and Apache people. The major speaking roles for American Indians would still go to non-Native actors like Burt Lancaster and Charles Bronson; but thankfully, progress has been made since those days and filmmakers and audiences have become more educated.

Progress has been gradual, but somewhat steady. Jay Silverheels ― a native of the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve near Ontario, Canada ― was perhaps the first legitimate Native American television star. From 1949 to 1957, he entertained TV audiences as Tonto, the Lone Ranger’s dependable ― albeit stereotypical ― Indian sidekick. The real Silverheels, though, was not limited by the stereotype. He recognized that fellow Native American actors needed to truly be masters of their craft in order to compete in the unforgiving film industry, so he founded the American Indian Actors Workshop in Echo Park, Calif., as a place where they could do that.

In 1956, John Ford’s film, The Searchers, earned praise for its more balanced depiction of American Indians. But “balanced” had a different meaning back then. The Navajos in Monument Valley who worked on The Searchers ― as extras, consultants or other staff ― were payed less than their white counterparts. At that time, too, they were not even allowed to leave the reservation without written permission from the government; so the fact that they were happy to have the work must be viewed in that light. But Ford’s efforts were progressive for his day and laid the groundwork for some of the more truly balanced movies to come.

It was in the 1970s that we really started seeing Indians portrayed more authentically and more prominently in film story lines. I remember seeing Little Big Man with Dustin Hoffman and noticing how director Arthur Penn showed the Cheyenne people actually laughing and crying, like real human beings rather than the predictably stoic and unemotional Indians we'd seen in Hollywood features. The Indians in his film were just like any other people -- some good, some not so good. They were not demonized just because they were Indian, as Hollywood custom had been before. Chief Dan George was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award, making him the first Native American to receive the honor.

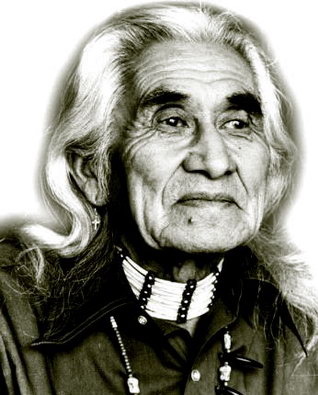

In 1975, Will Sampson delivered an inspired performance as Chief Bromden, one of the most pivotal characters in One Flew Over Cuckoo's Nest. But instead of crediting Sampson's acting skill and talent for his indelible depiction of the character (whom he made absolutely unforgettable while having almost no lines!), Hollywood press diminished his skill and talent to simply "acting Indian." Explaining why Will Sampson was overlooked for an Academy Award nomination, one director was even quoted as saying, "Why should an Indian receive an award for playing an Indian?"

That is how, in the eyes of many directors, Sampson's performance became a pattern for the big silent Indian. Sampson was typecast and did not have access to a wider range of roles that would have let us enjoy even more of his talent... a great loss for us. But Will Sampson was determined to make change, one way or another. He went on to be one of the founders of the American Indian Film Institute, producers of the American Indian Film Festival.

There were other noteworthy films in the 1970s, like A Man Called Horse. But then we had to wait until the early 1990s for Kevin Costner's Dances with Wolves, that had a modern take on American Indian people and how the Lakhota people of the plains might have lived. Some claim Kevin's story showed the Indians as too uniformly benevolent and white folks as simply evil. After all, though in real life Indian nations suffered much ill treatment at the hands of the government, not all real white people were bad and not all real Indians were angelic. But the overall message of the movie was a good one. Graham Greene, with his brilliant performance as Kicking Bird, joined the ranks of Oscar nominees with a Best Supporting Actor nomination.

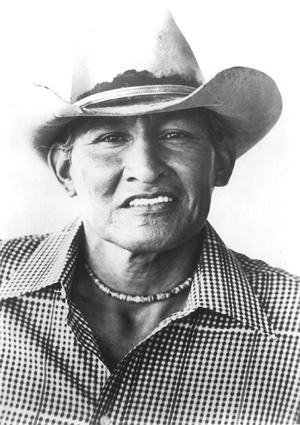

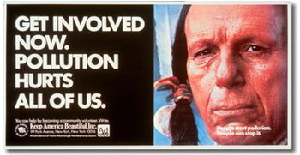

Hollywood also had Iron Eyes Cody. His ancestry became the center of some controversy when it became known that he was actually Italian by birth. But he did not just work as an Indian in Hollywood in the 1950s and '60s; he truly lived his life as an Indian. He can be credited as the most famous Indian in the world during that time. Even though he was not born an Indian, we should not forget that Iron Eyes Cody raised awareness for the American Indian people and also of the importance of environmentalism (Keep America Beautiful Public Service ad campaign) in a way that no one else was able to do at that time.

Even though he was not born an Indian, we should not forget that Iron Eyes Cody raised awareness for the American Indian people and also of the importance of environmentalism (Keep America Beautiful Public Service ad campaign) in a way that no one else was able to do at that time.

Nowadays, most producers do their best to hire actors that are from American Indian descent, or at least to some degree. But the issue is still a sensitive one. There is much bickering and infighting about who should get the available roles in Hollywood A-list films.

There have been mixed reactions to Johnny Depp playing the lead role of Tonto in the upcoming Lone Ranger movie; some people insist they must know, does he have Indian blood, and is it enough? The beautiful Q'Orianka Kilcher landed the lead role of Pocahontas in Terrence Malick's The New World, but some in the Native community were not pleased that she was of Peruvian and German descent. Rudy Youngblood, aka Gonzales, endured the same intense scrutiny when he got the lead role in Mel Gibson's film Apacalypto. But we don't hear much fuss about Jake Gyllynhall playing the Prince of Persia, Mel Gibson playing a Scot in Brave Heart or Anthony Quinn playing Zobra the Greek when In fact he was Mexican and Irish.

Some debate... if a Native from Canada can play an American Indian why can't an Indian from south of the border get the same shot? Makes you wonder, why do we insist on drawing lines between who is or is not allowed to play a role according to boundaries on a map? Add to this the irony that these boundaries are for the most part established by European settlers or modern day governments, and the dispute becomes even more complex.

These sorts of jealous conflicts between ethnic or national groups can happen anywhere. The city of Beijing banned the film Memoirs of a Geisha when both the Chinese and Japanese were offended by Chinese actresses playing traditional Japanese geishas. The actresses, Gong Li and Zhang Ziyi, were called traitors by both Japanese and Chinese people. I somehow think this reaction had little to do with the quality of their performances.

These sorts of jealous conflicts between ethnic or national groups can happen anywhere. The city of Beijing banned the film Memoirs of a Geisha when both the Chinese and Japanese were offended by Chinese actresses playing traditional Japanese geishas. The actresses, Gong Li and Zhang Ziyi, were called traitors by both Japanese and Chinese people. I somehow think this reaction had little to do with the quality of their performances.

At some point, when the fight begins to be political and not creative, maybe we have to step back from interfering with the artists -- the writers, directors and actors -- and allow them to make their art according to their vision. After all, it's called acting for a reason. Actors are supposed to become other people in their roles.

The most important thing is that we do not let our American Indian stories become lost in the debate. If instead we concentrate our efforts on making sure these too long ignored stories make it to the screen, there will be more opportunities for great American Indian actors like Graham Greene, Wes Studi, Adam Beach, Raoul Trujillo and many more, to shine. And as audiences become more discerning about authenticity, there will naturally be more chances for young Native actors to get a foot in the door.

A great step in that direction is that today, more American Indian film makers are finding ways to tell their stories from their unique perspectives. A superb forum for these films is The American Indian Film Festival, headed by the tireless and talented Michael Smith, which has been running for almost 40 years. It's the oldest and largest festival of it's kind in the world.

Another encouraging change is that some of our greatest non-Indian film makers are giving us a more authentic look at American Indian characters. From first hand experience I know that Anthony Minghella, Steven Spielberg, Ron Howard and Spike Jonze are a few who put a high priority on portraying American Indians with historical accuracy and as interesting people we can relate to. For weeks before filming began, Ron Howard had the leads in his film The Missing study the Chiricahua dialect of Apache language. We need to see more of this sort of character development.

Film and television are in the business of make believe, but at the end of the day we actors must be realistic. We only harm ourselves if we do not give credit to the producers and directors who take risks to broaden the cultural spectrum of modern film making, even if they don't always get it exactly right. And acting jobs will always be very limited, so we actors will survive only by accepting good roles when they happen to come along.

To stay in business, Hollywood must cast stars based mostly on their ability look the part, play the character, and generate box office dollars. After all, mere ancestry or DNA percentage does not always produce the best performance. But this is not all bad from the perspective of an American Indian actor. Won't so many more roles be opened up to us if we're also allowed to play other races if we can look authentic and pull it off?

Personally, it is what I bank on. I am a man of mixed blood and I have been extraordinarily blessed to be able portray many people from all over the world in my films. This is why I love what I do... I get to walk a thousand paths.

(All photos by permission as noted. All rights reserved. From top to bottom:

-Jay Tavare as Swimmer in Cold Mountain, © Stephan Berkman 2002

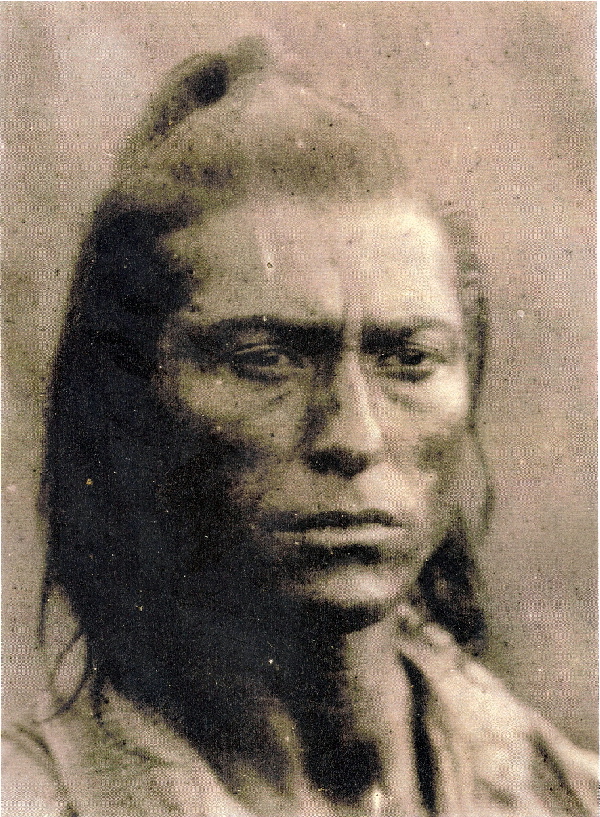

-Chief Dan George http://www.firstnations.de/img/06-0-1-george.jpg

-Will Sampson, publicity photo 1971

-Iron Eyes Cody, © Keep America Beautiful PSA campaign

-Graham Greene and Jay Tavare at The Missing movie premier, © Paul Greenstone 2003

-Wes Studi and Jay Tavare in Street Fighter, courtesy Jay Tavare

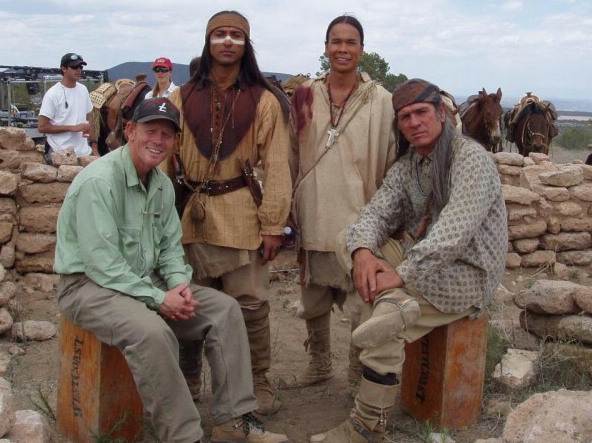

-Ron Howard, Jay Tavare, Simon Baker and Tommy Lee Jones on the set of The Missing, courtesy Jay Tavare

-Jay Tavare as Jay Tavare, © Josh Michael Shelton 2011