When we stop trying to define the truth for others we can begin to appreciate to what extent the society we inhabit is an ongoing negotiation between the secular and the religious. The social contract keeping the peace between us proves only as tolerant as the quid pro quo that guarantees its citizens' mutual survival. In many senses this quid pro quo, as variable, even erratic, as it may prove to be with the passage of new laws and the election of new representatives, is as important to the climate of peace and prosperity of the society as is the national constitution and laws guaranteeing religious freedom in modern democratic states. In essence only two primary principles have to be agreed to. That the religious must recognize and respect the autonomy of the individual. And that the secular must refrain from infringing on the right to worship the faith of choice. Whether it is the secular or the religious that predominates in a society, or even a true balancing of the two, the social contract maintaining that balance assures the protection of each, their properties and communal doctrines, rituals and codes of morality, visions of transcendence -- all to be spared the defilement and persecution of former authoritarian and suppressive rule either of the religious or seculars.

To understand what the secular person and the secular society are, we must at the same time understand the religious person and society that the secular has diverged from. There is no secular sensibility and sociology without there being a religious mysterium and community that receives the criticism of the secular. For this reason the secular only has meaning in relationship to the religious -- though the secular has other identities that are his and her own (the modernist, relativist, materialist, nihilist, etc.). And most importantly, to be facilitated by the secular. For the secular zone enables the communities of different religions to mingle for the purpose of all the business required to sustain life. It is for such facility that the secular zone was invented by the more pragmatic religious.

The secular is not atheistic, as it is often mistaken to be. Atheism is a belief in the non-existence of any and all deities to the point of being dogmatic. The atheist even makes the same primitive epistemological decision as the believer in God, which is to trust a belief to correspond with a reality s/he cannot possibly know -- in this case the nonexistence of God. The secular is more efficiently defined by its common usage and structure as the communal zone in which people of varying faiths and ideologies can coexist to conduct business, government and culture without the disturbance or debate, proselytizing, and social conformity that make everyday life in the cross-cultural agora of the new global community something less than polite, something more than profitable.

We know the social contract and the secular zone are working when we barely notice the secular-religious divide, if at all. Even then it is a matter of reportage on the side controlling the media -- and then for the side not being covered, the divide is as salient as a wall blocking a walkway. More often we know when the contract between religious and seculars is not working: the moment when the media reports a surge in violent attacks or vandalism against or by religious. Tragically, too often the media's attention means the social contract has already long been and repeatedly violated, and then reports focus only on the violent release of tensions, not the ongoing repressions that built up to tip an individual or a group to the decline at which things explode.

There is a clear distinction between an act of war or of terrorism that is motivated by secular or by religious breaches of the contract. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon by al-Qaeda were largely secularly motivated against American interference in MIddle Eastern affairs however much we hear "Allah willed it" intoned on videos released by al-Queda. The fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeni urging Muslims to assassinate Salman Rushdie, the Theo Van Gogh assassination in the Netherlands, the Charlie Hebdo assassinations, the November 13 Paris attacks, and all conflicts, killings, and demolitions of shrines, churches, mosques and antiquities waged by ISIS in Iraq and Syria, by stark contrast, are as religiously motivated as they are steps to attaining complete theocratic domination.

It is easy to see the terrorist attacks themselves being religiously motivated, but it is much harder to recognize, at least from the secular side, that the slights religious feel are aimed at them by the seculars are also religiously motivated. Atheism and agnosticism are faiths replete with supportive cultures as much as any religion's. This is the blind spot of seculars -- though many people who participate in secularism for its facility of making work and leisure less stressful do profess religious faiths. And by no means are secular populations any less engaged with the spiritual and material issues of a society simply because they stand alienated from institutionalized religions.

The blind spot for the religious manifests with their control of a legislature. An assumed superiority disallows them from seeing religion limiting the individual liberties of those apart from them particularly when their religious doctrines exclude us. They mistake the contract that protected and enabled them to assume stewardship of the law to be theirs to give to their God, not to continue its protection of the individual conscience that cemented their partnership with seculars before they assumed responsibility for the law. The religious too often, when in the majority, proceed to break the spirit of the social contract, which leaves the seculars faced with choosing to either resist the religious by legal means (boycotts, public dissent, voting out officials) or to take measures that are more disruptive of the society and obliterates the social contract. This is when seculars confuse their right to free speech as justifying and protecting them when they denigrate the symbols that publicly distinguish the faiths of religious. And this is a dangerous interlude, as the withdrawal from the social contract leads to lawlessness.

To forestall such an escalation of hostilities, the alienation of the other side is itself something the religious and the secular can learn from. For especially in a relativist society such as the democratic state professes itself, it is not what the religious or secular believe that is alienating, it is the degree to which the religious or secular retain the authoritarian and inflexible character that the religions had assumed over the centuries of their imperial histories. This pertains particularly to those faiths and ideologies -- Christianity, Islam, Confucianism, Hinduism, Communist Atheism -- that officiated imperial or state rule to the extent of issuing pogroms and genocides against their rivals.

Unless seculars have lapsed from a faith as adults, they are generally poorly informed of what the religious issues are apart from the more overt forms of physical assaults on religious and the vandalism of religious property; they are too often blind to the slights that seculars inflict on religious every day. It is the same lesson racists unconscious of their racism had and still have to learn. Even the most progressive seculars have a particularly hard time discerning that religious prejudice is no different than racial prejudice in that a faith profoundly defines the identities of people as much as race and economics. As horribly unwarranted as the Charlie Hebdo murders are, they are a response to a hate campaign as fascistic as the anti-Semitic pogroms of the Nazis. Had the killers taken the high-minded road of Mohandis Gandi, Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela, instead of advocating murder, they would have succeeded in showing the world that mockery of their faith is a heinous violation of the secular-religious social contract. Instead the bigotry of certain French seculars was made the far lesser crime by the violence of extremists who could have feasibly won a publicity campaign, if not a civil suit of religious defamation, against the Hebdo editors.

One source of the problem is that seculars tend to believe that the social contract for peace has its source in the Enlightenment philosophers. In fact the Enlightenment models for the social contract might never have emerged if earlier social contracts hadn't evolved with the scriptures of Vedic Hinduism, Judaism, Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and the numerous tribal social contracts that evolved into them. But religious or ideological beliefs should never supersede the social contract, as it is the social contract that in effect protects and preserves all forms of social intercourse. We may find this fact more palatable when realizing that we are always at the same time a believer in an idea and a nonbeliever in that idea's opposite.

Another misconception is that the social contract evolved as a high-minded deliverance from conflict when the history of brutality gives us reason to believe that the social contract more likely is a pragmatic outgrowth of being forced under extreme duress to see the necessary concessions to a conquerer will be mitigated by an early treaty in which a quid pro quo can minimize, even salvage, losses. But as Machiavelli has informed us, even the ruler who has taken a population by force can and should see the value in a social contract that benefits the conquered populations once the empire building and the territories and subservient populations get settled. The social contract is nothing if not the safeguard to economic and governmental longevity so long as benefits are "given little by little, so that the flavor of them may last longer".

Films that depict the tensions between the secular and religious:

It is arguable that among the most salient signs that a society has a viable social contract between seculars and religious is the porousness of the markets for its arts and entertainments. In the US, the entertainment industry has ebbed and flowed in its featuring of religious portrayals. Before the 1970s, Christian worship alone was portrayed when made central to a production, though Judaism was significant to Biblical stories. The decline in practicing religious in the West since the 1970s consigned even Christianity to the background of narratives, brought out usually only for the background depictions of marriage ceremonies and funerals, or for confessional scenes of the guilty. Broadway theatrical productions, however did feature religion prominently in Angels in America, The Book of Mormon, Lion King, Godspell, and the perennially revived musical, Fiddler on the Roof.

Since the 1980s, however, non-Christian religions increasingly shared that background, particularly Judaism, and in the last decade a surge of productions balancing Islam for both its protagonists and antagonists, though all too often for negative and exploitive portrayals. Since the success of Stephen Frear's 1985 film, My Beautiful Launderette, the independent film circuit has been more generous in opening to positive portrayals of Muslims, usually among transplanted or second-generation immigrant families in the US, Canada and Europe, and in rarer instances other religions indigenous to regions, such as the 2005 Academy Award nominee for best foreign film, Deepa Mehta's Water. In all these films, however, the tension that provided the topical tautness required simultaneously of good, even great drama and penetrating spiritual inquiry.

In the international market for religious-themed film, only Mel Gibson's 2004, The Passion of the Christ, ranks among the top box office grossers of history, ranking #61 (adjusted for inflation) among the top 500-grossing films in history. But before 1975, when religious films were not nearly so rare, three of the twenty top grossing films are religious, The Ten Commandments (#6), The Exorcist ( #8), Ben Hur (#13) and if we count the more marginal role religion plays in The Sound of Music (#3) that's four out of the top twenty films, or 1/5 the tally, a good percentage given that the other sixteen films cover a range of topics and interests. When counting The Robe (#46), The Bells of St. Marys (#53), that's seven out of the top sixty films, or more than 10% of the top-grossing films in history. Comparing that with only one production in the last twelve years at a time when the religious population has increased exponentially in the world gives us an idea of the degree of diffidence among film makers in their consideration of the religious film. (See Box Office Mojo DOMESTIC GROSSES

Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation.)

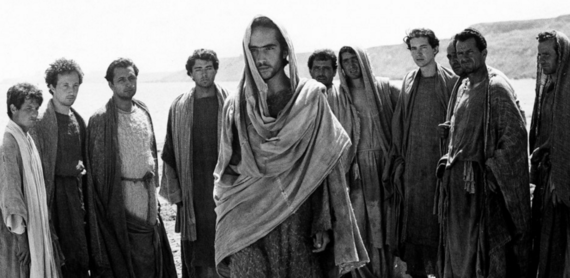

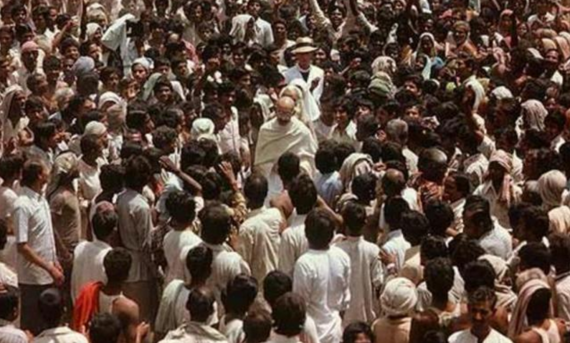

Among significant artistic world cinema, a short list of films made by and for people who prefer the humanistic and existential portrayal of spiritual crisis to the miracle spectacle geared toward the credulous is surprising long and richly rewarding. Not so surprising is the good news that the spiritual and religious film bring out the more discerning and aesthetic sensibility in a director and cinematographer, for which we have a crowded array of brilliant gems to advocate as evidence. While some embrace faith, others are critical, a few scathing, yet all possessed of a heightened view, even when secular, of religion and spirituality. The very short list includes Carl Dreyer's Day of Wrath, 1943 and The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928; Robert Bresson's Diary Of A Country Priest, 1951; Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal, 1957, Through A Glass Darkly, 1961 and Winter Light,1962; Kon Ichikawa's The Burmese Harp, 1956; Franco Zeffirelli's Brother Sun, Sister Moon, 1972; Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew, 1964; Satyajit Ray's Devi, 1960; Andrei Tarkovsky's

Andrei Rublev, 1966; Robert Attenborough's Gandhi, 1982; Martin Scorcese's Kundun, 1997 and The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988; Nicolás Echevarría, Cabeza de Vaca, 1991; Bernardo Bertolucci's Little Buddha, 1993; Spike Lee's Malcom X, 1992 (it's transformative ending); Francois Dubeyron's Monsieur Ibrahim, 2003; Deepa Mehta's Water, 2005; Luis Buñuel's Nazarin, 1959 and The Exterminating Angel, 1962; Ousmane Sembène's Moolaadé, 2004; Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry, 1997 and Where is the Friend's Home?, 1987; Shekhar Kapur's Elizabeth, 1998; Kim Ki-duk's Spring, Summer, Winter, Fall, and Spring, 2003; Jafar Panahi's, The Circle, 2000; Chen Kaige's Yellow Earth, 1984; Joel and Ethan Coen's A Serious Man, 2009; Hayao Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke, 1997; Mike Leigh's Four Days In July, 1984, Shirin Neshat's Women Without Men, 2009; Parvez Sharma's A Sinner In Mecca, 2015; and as unparalleled comic fare, Federico Fellini's, Roma, 1972.

G. Roger Denson is an agnostic and a relativist.

Read Part 2, Religion vs. Secularism In Art and How Shahzia Sikander and Jim Shaw Turn Social Alienation Into Spiritual Engagement, on HuffintgonPost Arts and Culture.