Now that Labor Day has come and gone, many parents have their hands full in the morning as they juggle getting ready for work and getting the kids off to school. And while their kids' schools mostly look the same as last spring, there are major differences in some of their playgrounds, which are being designed for new purposes.

A few of those playgrounds will be in Philadelphia, where they are part of a new environmental design movement and are at the same time helping the city solve a pollution problem. When Michael Nutter became Philadelphia's 98th mayor in 2008, he pledged in his Green2015 plan to create 500 more acres of green space in the city, no small feat in one of the oldest, most-densely developed cities in the country. Part of that plan called for "greening" playgrounds and recreation centers by taking out pavement and replacing it with soil and plants and other porous materials which allow water to seep into the ground, rather than simply running off into streets, gutters, sewers, and ultimately into streams and rivers.

There are three such efforts underway in north Philadelphia. At William Dick Elementary, six acres of cracked, impervious asphalt are being converted to an artificial turf field with underground storage for excess rainwater, which will also be absorbed by nearby trenches and gardens. New tree trenches at The Hank Gathers Recreation Center and new porous basketball courts at Collazo Park will also serve as means of water retention.

William Dick schoolyard as it looked before

Plans for William Dick schoolyard renovation

Beyond being safe, attractive places to get outdoors and get exercise, the three facilities will help the city solve a major problem: When heavy rains overwhelm the city's aging water system, untreated sewage is dumped directly into the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers in volumes as high as 14 billion gallons a year.

Philadelphia is not alone. Many other U.S. cities are looking for ways to capture water which might otherwise run off concrete and asphalt into storm sewers in combined sewer systems, forcing a diversion of both storm runoff and raw sewage into nearby waterways. That toxic stew includes sewage waste and high levels of phosphorous, pesticides, increased concentrations of a host of metals, including mercury, nickel, chromium, lead, and zinc, as well as organic contaminants such as PCBs and PAHs. More than 70 cities are facing legal orders, known as consent decrees, from either state regulators or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), requiring them to clean up the water they are dumping into streams and rivers. To do so, many are turning to "Green Infrastructure" (GI) that can help tackle this issue.

Green infrastructure is a technical term, first coined in the 1990s, which has come to define a type of design and construction which highlights the importance of using natural components. The phrase is ill-defined -- type "green infrastructure" into a Google search and it will return more than 140 million entries. By some definitions, green infrastructure includes preserving and restoring natural features such as forests and wetlands. On a smaller and more engineered scale, the practice involves "green" roofs, porous pavement, planted areas -- known as "rain gardens" -- designed to absorb runoff, and the like. Some suggest that green infrastructure is not built at all, but simply consists of natural elements like trees, plants, and soil.

While green infrastructure has become popular in recent years as part of the environmental movement and urban design, it has actually been around for a long time. In the 19th century, when Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were creating many of our best-known city parks, they captured storm water in an intricate system of underground drainage tiles and pipes, and directed it back to nearby lakes and ponds. In Boston's Back Bay Fens, an early version of GI was first used to clean polluted waters using natural landscape typologies. But that approach changed in the 20th century, at which time cities like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and others built large areas of impermeable asphalt, designed to funnel rain water into sewers and away from the ground.

Now, many cities are seeing opportunities in the need to clean the water. Many cities face fiscal constraints that don't allow them to build new parks, but are nonetheless obligated to manage water better -- even to the point of creating major new infrastructure to protect communities from catastrophic damage from storm surge, flooding rivers, and other severe weather events. Parkland in U.S. cities makes up between 2.3 and 22.8 percent (with a median of 9.1 percent) of city land area. With the opportunity to build new, functionally layered landscapes that serve to process storm water, abate storm surge and serve as esthetic and recreational assets, parks and green infrastructure may be entering a prolonged, perhaps permanent, symbiotic relationship.

Are all parks a form of GI? No. But properly designed, constructed, and managed, GI can be a park, especially under broader definitions. For example, the 2,000 Greenstreets (i.e., greened traffic islands) created by the City of New York, prior to their being formally engineered as GI, were considered "parks" by the Parks Department. They were mostly very small properties, but what they had in common was plants and trees, and often sidewalks and sitting areas or benches. They played a role in lowering the urban heat island effect, absorbing carbon dioxide and particulate matter, providing oxygen and habitat, and creating many small islands of beauty in otherwise bleak landscapes.

The American Society of Landscape Architects, following the example of LEED, worked with the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at The University of Texas at Austin and the United States Botanic Garden beginning in 2005 to develop the "Sustainable Sites" and rating systems for sustainable landscape design. And in an unusual partnership, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation and the nonprofit Design Trust for Public Space worked with professional peers beginning in 2008 to develop and publish guidelines for building sustainable parks. The result, called "High Performance Landscape Guidelines: 21st Century Parks for NYC," have a particular focus on storm water management.

Sustainable Urban Development Meets Water Pollution Control

At the same time the guidelines were being developed, some cities were taking macro approaches to sustainable urban development, including Seattle, Portland, New York, and Philadelphia. Portland and Seattle were among the first cities to use GI to capture storm water runoff in vegetated bioswales. New York City's "PlaNYC" and the "Greenworks Philadelphia" were among the ambitious plans developed under the leadership of Mayors Bloomberg and Nutter in the first decade of this century. And many of those same cities were also confronted with having to clean up their storm water runoff to address federal Clean Water Act violations and consent decrees.

The combination of proactive plans for sustainable cities and ways to comply with federal law also led to cities developing plans for storm water management that included heavy GI components. In New York City, a "Green Infrastructure Plan" was developed by the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and $1.6 billion was allocated toward the development of GI. This resulted in the proliferation of green roofs, blue roofs, water cisterns, bioswales, the"Blue Belts" the traffic-island"Greenstreets," and even specially designed tree planting systems known by the cumbersome title of "Right of Way Street Tree Bioswales."

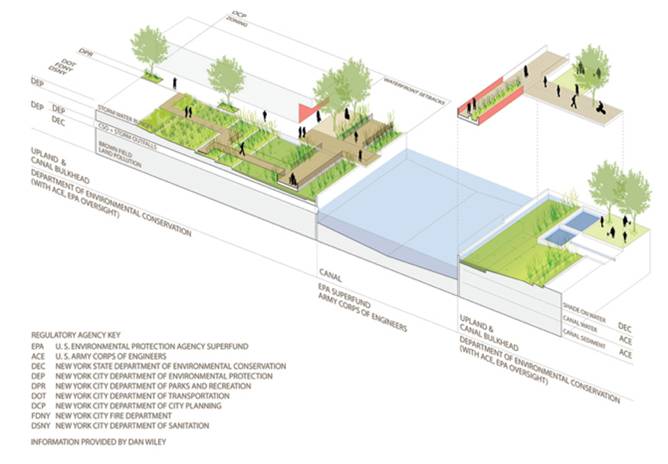

In New York City, landscape architecture firm Dlandstudio has developed a plan to capture and process storm water runoff in street-end "Sponge Parks" before it enters the heavily polluted Gowanus canal. The design itself is complex, but even more complex are the layers of governmental agency oversight and approval involved in the project (see image below), slated to begin construction this year. Construction is also complete on a prototype system Dlandstudio developed with the help of the Regional Plan Association to capture and phyto-remediate runoff from an elevated highway in Queens above a creek that flows through Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

Mapping Complex Regulatory Responsibilities along the Gowanus Canal, New York. Credit: Dlandstudio

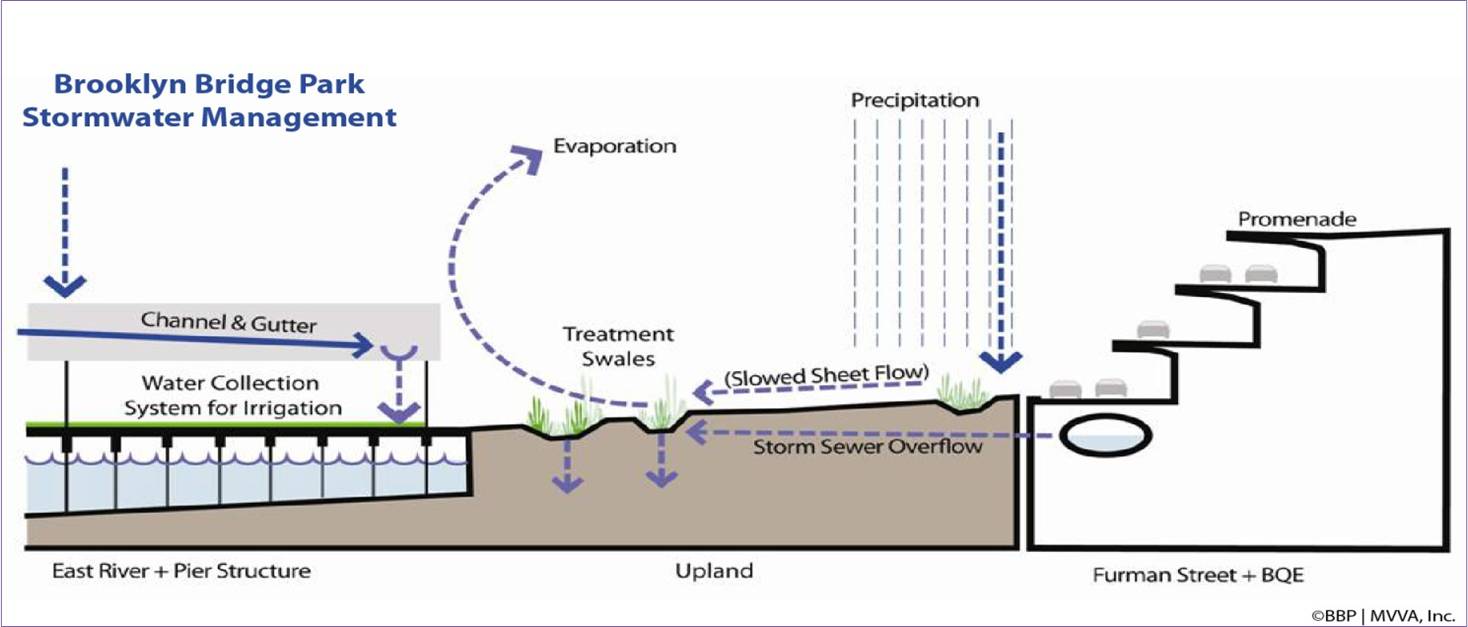

On Brooklyn's formerly industrial waterfront, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates has designed Brooklyn Bridge Park as the ultimate sustainable park, incorporating hills constructed of recycled stone from a nearby tunnel-digging project, and a vast underground water storage system that captures storm water in the landscape for irrigation purposes. This landscape also performed admirably when much of the park was inundated with saltwater by storm surge from last fall's disastrous Superstorm Sandy. In Queens' Fort Totten Park, landscape architect Nancy Owens created a new park landscape in a vacant site of former army housing, designing a vegetated bioswale which absorbs and channels storm water runoff away from structures, and creates an enriched park habitat.

Diagram of storm water management system in Brooklyn Bridge Park. Credit: Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy/ Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates

In many cases, GI is installed in newly created parks, but it can also be used to strategically redesign existing parks and playgrounds, as will be explored in the second installment next week.

A longer version of this article was originally published in "The Nature of Cities" blog. Marianna Koval, a consultant for the Trust for Public Land, provided research on the use of Green Infrastructure in parks, some of which is incorporated in this piece. Additional assistance was provided by Cecille Bernstein, also of The Trust for Public Land.