Last month, gasoline prices hit their highest ever level for February -- an eye-watering $4.69 per gallon in Manhattan. Predictably, since this is an election year, politicians vie to cast the blame onto others.

Barack Obama is most obviously in the firing line: he's been president for three years. Why the heck hasn't he fixed global energy markets yet? What's he been doing all this time? More specifically, Republicans have slammed the president's nixing of Canada's Keystone XL pipeline, no matter than any impact on prices is years away.

Obama's fightback has proceeded on several fronts. He's sought to deflect blame for high prices onto the tax loopholes and subsidies granted to Big Oil. He's called attention to his payroll tax extension which doesn't solve the price issue but at least helps people to pay for it. And he's used his Press Secretary Jay Carney to remind voters of his 'all of the above' approach to energy -- an approach which has so far lifted domestic oil and gas production in every year of his term of office.

These dogfights don't feel very new. The world faces a fundamental problem with rising energy costs. The political opposition blames the incumbent. The incumbent does his best to remind voters of a few basic facts of life -- mostly that oil is a global market that lies beyond the control of the U.S. president -- but ends up resorting to those fail-safe political tactics: flinging money at the problem (payroll taxes), blaming someone else (naughty Big Oil) and lastly those "evil empire" speculators (Wall Street).

And yet the background here is importantly different in a couple of respects.

First, Iran is now within touching distance of exiting its zone of vulnerability. By the end of the year, it'll be effectively immune from outside attack and well on the way to finally possessing nuclear capability. According to the Economist, Benjamin Netanyahu 'says privately that on his watch Iran will not be allowed to take an irreversible step towards the possession of nuclear weapons.' That irreversible step is about to happen -- unless Israel launches an attack in the next few months. Iran has promised to respond by blocking the Strait of Hormuz, the narrows through which 20% of all the world's oil is obliged to pass.

There are, as it happens, serious reasons to doubt that an Israeli attack can be effective. It's also questionable whether Iran's feeble armed forces can effectively block the outward flow of oil from the Gulf. But those military reservations are hardly likely to assuage the price of crude oil, which has risen nearly 40% since last October. It should hardly need saying that a savage oil price spike is likely to thrust a frail world economy back into intensive care. I would judge that if we see any type of supply shock the oil price is likely to touch $200 or even $250 a barrel before the year is out. The consequences for economic growth are likely to be violent.

Disturbing as these thoughts may be, they're disturbing in a way that don't necessarily call for policy change in Washington. The Middle East has long been an unstable and dangerous place. The U.S. manages its interests as best it can. There's a limit to what it can do. And, in the eyes of the mainstream media, that's usually where the story ends.

But really, that's where the story starts. If the country is faced with an impending spike in the price of its most important resource, the government's monetary authorities should be seeking to ameliorate or counteract its effect -- yet they're doing the exact opposite.

At the most basic level, no one disputes that, in the long run, there is a very close relationship between the money supply and prices. (The Bundesbank says so and it ought to know.) Since the Federal Reserve -- and its fellow central banks -- have been expanding their balance sheets like crazy, that alone ought to make us worry about a tide of impending inflation.

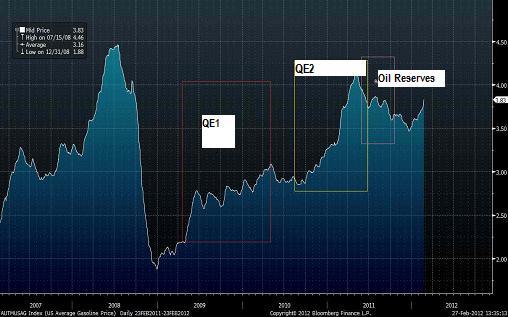

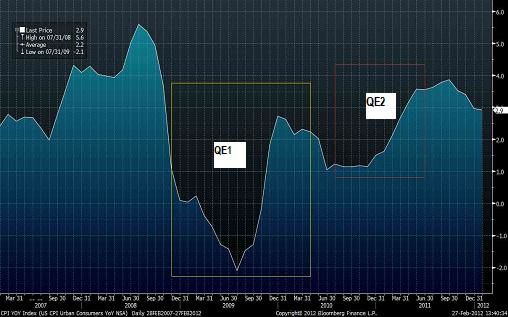

But these worries don't depend on some long-term link that's invisible in the here and now. These stunning charts from Bloomberg demonstrate that the periods of quantitative easing (English translation: printing money) have coincided with upward spikes in the price of gasoline and the consumer price index.

Which is precisely what you'd expect. Ramp up the supply of money while depressing the U.S. dollar and watch the price of commodities and other assets skyrocket.

Indeed, that inflation is happening well beyond the energy markets alone. There's gross inflation in the market for financial assets. U.S. Treasuries have never been as underwhelming a buy as they are now -- yet their prices are at record highs. Same thing in the equity market. The world is trembling on the brink of hot war in the Middle East, collapse in the Eurozone, and the world financial system remains acutely fragile. At times like this, you'd expect equity prices to be trembling in a corner someplace, and instead they're striding confidently to pre-crisis highs.

In short, the Federal Reserve is creating asset bubbles. Just as it enabled the tech bubble, the housing bubble, and the subprime bubble. Our current bubble is evident primarily in many asset markets and the market for oil and -- so far -- any damage has been limited. But that's always true of bubbles. No one gets hurt in the upswing; that's why they persist. Yet the bigger the bubble grows, the worse the final outcome. For 20 years now, the Fed has sought to escape the consequences of one bubble by inflating another bubble someplace else. That game has got to come to an end sometime and that time is now.

The primary causes of high oil prices don't lie in Washington. They have to do with a limited resource that's mostly located in unstable and troubled places. But our monetary response has been as wrong as it's possible to be. Catastrophically wrong. And we're about to reap the consequences.

Mitch Feierstein is the author of Planet Ponzi.