As you enter the new exhibit at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., you see an image of lovely young girls dressed up for a dance class. Some of the girls are Jews and some are not, but you can't tell which are which. In Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania, in 1935-1936, their lives are intertwined.

Then you hear the woman's voice. Baffled. Wondering. Three-quarters of a century later, her bewilderment is still with her. "We were friends, I thought." Once a friend, now an enemy -- how could it have happened?

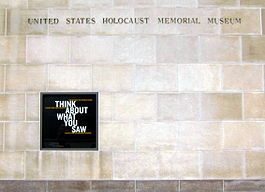

"Some Were Neighbors: Collaboration and Complicity in the Holocaust," the museum's newest exhibit, is open for visitors through 2016 and is also accessible online. It is a pertinent place to visit as we observe International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which commemorates the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1945, on January 27.

For 20 years, the museum has helped visitors to ask themselves important questions. This exhibit is no exception. It provides an extraordinary range of information while expertly prodding visitors to engage in moral inquiry.

Yet to my mind, the exhibit does not go far enough. In its focus on individual choice, it fails to explore how we can create the social conditions that support individuals in standing up against hatred.

What is new, and welcome, is the exhibit's unblinking focus on how ordinary people were involved in the machinery of destruction. We see onlookers, classmates, co-workers. We hear the words of some who participated in mass murder, as well as others who resisted.

The exhibit does an exceptional job of exploring the complex mix of anti-Semitism, anti-communism, nationalism, social and economic pressures, temptations, loyalties, and lust for revenge that swirled within the European population during World War II.

We're shown a photograph of Jews being herded to the trains, while arrows direct our attention to those who stand by and watch. "What are the onlookers thinking?" the signage asks. "Does their mere presence at the event make them complicit in the crime?"

We see people plundering the clothing, furniture, and household goods left behind by their deported Jewish neighbors. "Are these people complicit by benefiting from the misfortune of others?" we're asked. "Does it matter whether they are poor or not?"

Some will worry that examining the complex motives of "the neighbors" might lead us to conclude that it's "only human" to join in persecuting others. I don't share that concern. To my mind, the more we understand the collaborators -- and even see how in some ways they are like us -- the better equipped we will be to resist joining in future genocides. The experiences, the conflicting impulses, and the moral struggles of ordinary people in extraordinary times must be carefully studied.

Like the museum itself, the exhibit is designed to make people uncomfortable.

"The documentation of widespread collaboration and complicity of individuals like ourselves," says curator Susan Bachrach in the museum's magazine, "should disturb everyone."

Throughout the corridors of the exhibit, we're prompted to turn inward.

"We want people to think," museum director Sara J. Bloomfield told the Washington Post, "What would I have done? What will I do?"

But as we rightly question ourselves as individuals, I believe we must do something more as well. We must turn our gaze outward and ask how we can act with others.

During the most terrible times in the 20th century, solidarity was often difficult if not impossible. In that time, as in so many other times, it was much easier to stand by than to stand up. The only way we will prevent future genocides, I believe, is to work together to create the kind of society where you can stand up. Where it's not up to each individual to make the terrible life and death decisions alone, to decide alone whether to put your head up and risk getting it blown off.

Without letting individuals off the hook, I believe we must ask ourselves:

How do people join together to resist the forces of hatred?

How can we best equip ourselves and our fellow human beings to use the tools of civic engagement and social action?

Morality is not only an individual but also a social matter. To prevent genocide, we must do more than appeal to individual conscience. We must also nurture habits of civic and social activism. Only then will enough of us gain the ability to step up, speak up, and stand up against the forces of hatred.