Anyone who has been privileged to hear Barbara Cook in concert or cabaret over the last thirty years is aware that she talks in a bright, refreshing but decidedly honest voice that is always friendly, but she is no pushover. Anyone who knows Cook from her legendary musical comedy roles (introducing "Glitter and Be Gay" as the heroine Cunegonde in Leonard Bernstein's Candide, "Till There Was You" as Marian-the-Librarian in Meredith Willson's The Music Man, and "Ice Cream" as Amalia Balash in Bock & Harnick's She Loves Me)--or has seen photos of Cook as the same--is aware that she has had something of a severe weight problem. And anyone who has heard her perform that Peach State anthem "Georgia on My Mind" is aware that she always prefaces it by saying that she spent her childhood trying to get out of Georgia and never much cared to go back.

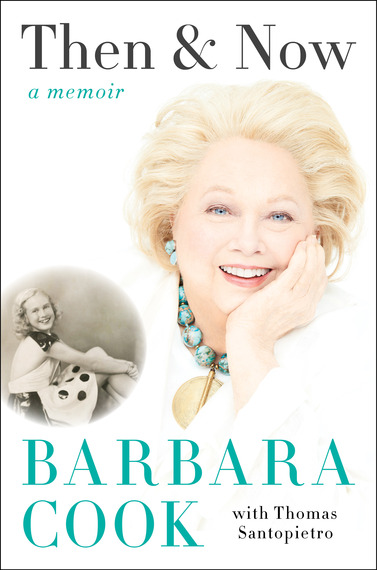

What we weren't aware of--and what we now learn, in Cook's own words in her memoir "Then & Now" (written with Thomas Santopietro)--is just how severe an existence she has led. She makes it clear that she early-on recognized the power of her singing voice; that voice has not only sustained her through a long, up-and-down career--she is now 88--but seems to have been her salvation when, on several occasions, anyone else might have just given up altogether.

While being outspoken, Cook is also modest; hanging her dirty laundry on a clothesline in the front yard is not her style. She prefaces the book, though, by saying that her aim is to demonstrate to others who are addicted, destroyed, washed-up or severely depressed that there is life, contentment, and even--potentially--high success on the other side. If she could do it, then you can too. And Cook makes no bones about how desperate she was, noting that she would sleep through the day and "I didn't shower or brush my teeth for days at a time." She goes on to confess that "I was so broke I was stealing food from the supermarket by slipping sandwich meat into my coat pocket."

Not what we expect to hear from Barbara Cook, Broadway's favorite soprano.

Cook makes no excuses, but reveals her troubles (courtesy of what sounds like years and years and years of therapy, not all of it helpful). It starts in 1928 with a mother on the level of Gypsy Rose Lee's mother, only less feeling. When Cook was three, her 18-month-old sister died of double pneumonia; Barbara's fault, said her mother. When she was six, her father packed up and walked out; Barbara's fault, said her mother. By this point, the country had entered its own Depression; Barbara and her mother moved in with her grandmother, living in poverty in Atlanta. Her spinster aunts worked in a coffee factory and would hide beans in their bloomers, so the house always had coffee at least.

But Barbara loved listening to the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts on the radio; and when she was seven, she entered a contest at a movie house and won a prize of fifty cents doing a "military tap." In high school she was ostracized as one of the poor girls, wearing the same clothes every day, but she began to realize that she had talent. By fifteen, she was performing in burlesque--not as a stripper, but as part of the dancing chorus--and bringing in money; her day job was as a civil service filing clerk and secretary. In 1948, at the age of twenty, her mother took her on a two-week vacation to New York. Barbara never returned South, sending mother home alone.

Cook started working; at Tamiment, the Catskills summer camp for adults that served as an incubator of Broadway talent, and at nightclubs like The Blue Angel. In 1951 she landed a major role in a major Broadway show: Yip Harburg's Flahooley, a controversial, highly-politicized musical that quickly flopped. (The stress of the troubled tryout sent her up to 136 pounds, she precisely recalls.) Her voice quickly got her into touring companies of Rodgers & Hammerstein's Oklahoma! and Carousel, in which she made strong impressions as Ado Annie and Carrie Pipperidge. (Both productions stopped at New York's City Center, bringing Cook more notice than she'd achieved with Flahooley.) She returned to Broadway in 1955 with a prominent role in the moderate hit Plain and Fancy, which immediately led to star-making appearances in Candide (1956) and The Music Man (1957).

"Then & Now" is filled with backstage anecdotes, of course. While learning a difficult passage of "Glitter and Be Gay," she naively informed Maestro Bernstein she had a better way to do it. She demonstrated, to which he said: "You're absolutely right, why didn't I think of that?"

Her descent had its roots in life with mother, plus relationships with the men in her life. This started with abandonment by her cherished father. In 1951, she met actor/acting coach David LeGrant--he played Ali Hakim to her Ado Annie--and they married the next year. (Cook's mother, typically, sent a letter to LeGrant's mother: "Your lousy stinking Jew black-balled son wants to marry my gorgeous daughter. . .") The marriage brought Cook her beloved son Adam in 1959, but otherwise proved stultifying; while happily living on Cook's earning, LeGrant strictly controlled everything she did. This helped turn Cook to alcohol, which had long been a problem in her family. She finally divorced in 1966, and her increasing alcoholism eventually drove Adam to leave her to live with his father--which only accelerated Cook's downward spiral.

Professionally, her musical comedy career more or less ended in 1964 with the failure of Something More! The show did bring Cook her one successful and happy relationship, a secretive one with co-star Arthur Hill (best known as the Tony Award-winning star of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?). But Hill was unwilling to leave his wife and family, so the affair was doomed. Cook moved into the non-musical field, as replacement (1965) for Sandy Dennis in the long-running comedy hit Any Wednesday and as costar of Jules Feiffer's Little Murders (1967). At which point the alcohol and the ballooning weight caught up with her. She could barely get herself to work--Cook made her final musical comedy appearance in 1971 in The Grass Harp, a seven-performance flop--and she was soon homebound, with a half-gallon of Gallo Mountain Chablis a day and all but cut off from the world and from show business.

It wasn't until 1974 that she joined up with musical arranger/pianist Wally Harper, who helped her devise a second career as a cabaret singer. This was eventually successful, with Cook becoming a top attraction and easily packing places like Carnegie Hall with enraptured audiences. But it took a while for Cook to stop drinking and recover some semblance of health, while the talented Harper steadily drank himself to death.

But that's all part of the story. And what a story it is, told in a bright, refreshing and brutally honest voice, in a manner that you would expect from Barbara Cook--though the excesses of her harrowing journey are certainly unexpected. Get yourself a copy of "Then & Now" now and plunge into it, giving yourself breaks here and there to listen to Barbara singing Candide, The Music Man and She Loves Me.

.

Then & Now, A Memoir by Barbara Cook with Thomas Santopietro available from Harper