Today's American supermarket carries more than 38,000 products, thousands of boxes of cereal, yogurt in every size and flavor, rows and rows of condiments and frozen food products that make your eyes glaze over.

It is easy to be struck by decision paralysis when faced with so many options. But if you look at the packages a little closer, just behind the brand names, this illusion of choice quickly evaporates. And if you look even closer you will see the faces of millions of rural farmers living in poverty and hunger.

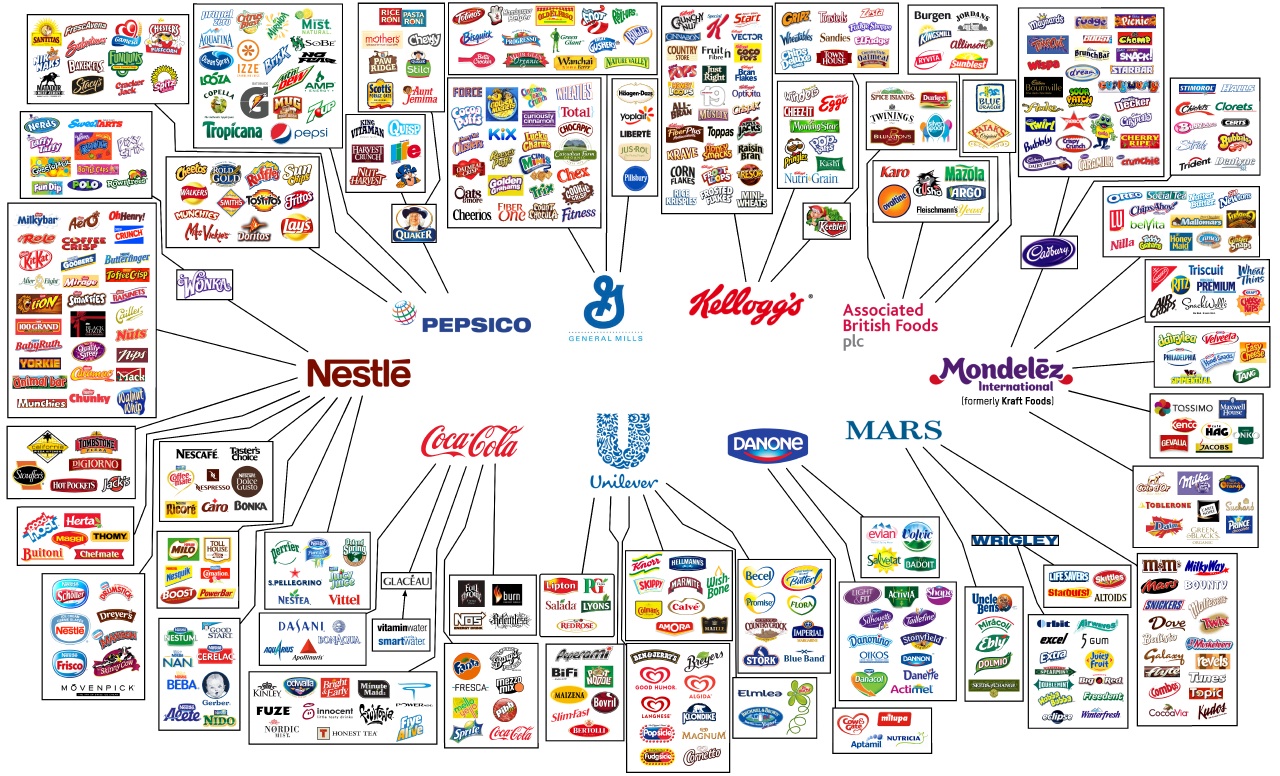

Most cans, boxes and bottles are made by just a handful of companies. In a world with 7 billion consumers and 1.5 billion food producers, no more than 500 companies control 70 percent of food choice. Among these companies, an elite group of ten food and beverage giants have consolidated immense market power. Associated British Foods, Coca-Cola, Danone, General Mills, Kellogg, Mars, Mondelez Internatonal, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever -- "The Big 10"-- wield power on par with governments large and small.

Collectively they generate revenue, more than $450 billion per year, equivalent to the GDP of the world's low-income countries combined. Their influence extends across the food system, from conditions on small farms in Nigeria to the placement of products on supermarket shelves in Des Moines.

This consolidation has made it difficult for consumers to keep track of who owns which products and the "values" behind a brand. Even products once produced by smaller companies like Odwalla or Stonyfield Farms are now owned by the "Big 10." As a result already vulnerable small-scale farmers around the globe now have even fewer buyers for their products, leaving them with an increasingly weak bargaining position.

With this influence comes great responsibility. The choices these ten companies make at corporate headquarters help sway whether or not communities halfway across the globe are able to eat.

Today 450 million men and women labor as workers in agriculture and in many countries up to 60 percent of these workers live in poverty. Up to 80 percent of the global population who are considered "chronically hungry" are farmers. The use of valuable agricultural resources for the production of snacks and sodas means less fertile land and clean water is available to grow nutritious food for local communities.

Changing weather patterns due to greenhouse gas emissions -- a large percentage of which come from agricultural production -- is making things even worse for these small-scale farmers.

These are facts the food and beverage companies acknowledge, but are doing little to address.

That's why we at Oxfam created the "Behind the Brands" scorecard that for the first time scores and ranks the agricultural policies, public commitments and supply chain oversight of "the Big 10". We did 18 months of research into how these companies are orienting their supply chains to see if they are making good faith efforts to reduce poverty, hunger and protect the environment. And we created easy to use tools for anyone to hold companies accountable by contacting them directly via Twitter and Facebook to ask them to do better.

The findings are troubling. While some companies have already recognized the business case for sustainability and have made important commitments that deserve praise, none of the "Big 10" companies are moving fast enough. Not one is making an adequate effort to turn around a 100-year legacy of relying on cheap land and labor to make mass products at huge profits, with unacceptably high social and environmental costs.

Most worrisome is that food and beverage companies themselves often know little about their own supply chains. Where a particular product is grown and processed, by whom, and under what conditions are questions few companies can answer accurately let alone share with consumers.

However, consumers are increasingly savvy and social media is making it easier than ever for individuals to make their voice heard. The want to know who is producing their food -- they want to see the truth behind the brands they buy. Investors are asking tough questions of companies about whether they are addressing risks like climate change and water scarcity.

With appropriate public pressure these companies could champion serious efforts to tackle some of the most difficult challenges facing the food system.

The system is poised for change. Now is the time for all of us to show companies that it is in their interests to lead. No brand is too big not to listen to its customers, and if enough of us urge the "Big 10" to do what is right, they will have no choice but to listen.